SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BANGKOK, Thailand – Island nations like Fiji and the Maldives are almost at the “point of no return” because of rising sea levels, a leading climate negotiator warned on Friday, September 7.

As well as losing land and infrastructure to encroaching oceans as the planet heats up, many islands are also facing extreme flooding and damage from tropical storms, warned Amjad Abdulla, head negotiator for the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS).

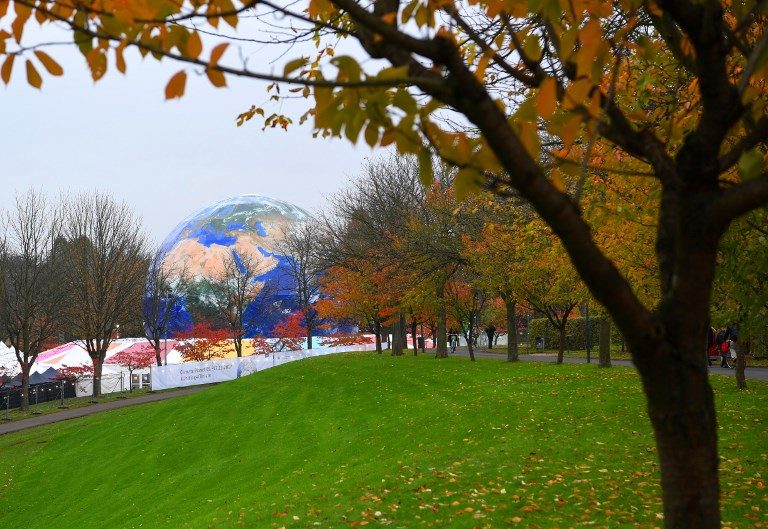

With experts from across the planet locked in key talks in Bangkok aimed at breathing life into the Paris Agreement on climate change, Abdulla said time had “already run out” for some countries.

“Our islands are at risk. We are doing more than our fair share with our limited resources,” he told the Agence France-Presse on the sidelines of the six-day conference.

“What we are saying to the international community is that we do not have adequate financial, technological or human capacity in terms of alleviating the issue of climate change – we need international cooperation so we can all survive on our islands.”

The 2015 Paris deal – which must be adopted by signatory nations by December – aims to limit global temperature rises to “well below” two degrees Celsius and to less than 1.5 degrees if possible.

The most persistent sticking points in negotiations revolve around money. (READ: Climate action could add $26 trillion to world economy – study)

The Paris Agreement has promised $100 billion annually from 2020 to poor nations already coping with the effects of climate change.

Developing countries favour outright grants from public sources, demand visibility on how donor nations intend to scale up this largesse, and object to under-investment in adapting to climate impacts.

Rich countries want more private capital in the mix and prefer projects with profit potential.

Although responsible for only a tiny percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions, the very existence of island nations are under threat from rising sea levels.

“We are very behind. If the world had adequately addressed the issue we wouldn’t still be negotiating and people would have been able to adapt and have a happier, more prosperous lifestyle,” Abdulla said.

“We are on the front line. But this is a global issue and it can be only addressed at the global level.”

‘Traumatic’ changes

Island nations want a better idea of what sort of funding they can expect from richer states to help develop renewable technology and build up local defences against the rising seas.

They also want commitments to help with the unique “loss and damage” derived from sea level rises and other impacts including storms and salt water intrusion.

“People are losing their livelihood, losing their homes,” said Abdulla.

“From the perspective of us in the Maldives, we are moving people to safer places, creating some kind of protection so that people can still survive.

“Now is almost the point of no return. The cost of adaptation is going to be massively scaled up. It’s not cheap even now and we see that the cost is going to escalate.”

Delegates at the Bangkok conference aim to produce a draft text of “streamlined” options that ministers and heads of state can push across the finish line at the December UN climate summit in Katowice, Poland.

Abdulla said he was optimistic a consensus would be reached, but stressed things “are not moving forward how we would have wanted.”

“We don’t have the luxury of time. It has already run out,” he added.

Finding a road through dozens of contentious and unresolved issues from the Paris accord carries particular urgency for Abdulla, who grew up in the Maldives and still remembers a time when most people lived in wooden huts, and electricity, quality schooling and healthcare were rare.

“Now, there’s no island without a school. They all have healthcare facilities, pharmacies, there are universities and people’s livelihoods have changed dramatically.

“Telephones, cable TV, internet. Schoolkids now have tablets. We have improved hugely. And it’s all under threat,” he said. “It’s traumatic.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.