SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Long before “sustainable natural resource management” became a byword, the Maeng tribe in Tubo, Abra already observed kaynga, their term for taking care of nature along with people.

Their indigenous resource management system, practiced since the time of their ancestors, already included sustainable methods of mining, hunting, gathering, fishing, managing pastureland, and dealing with solid waste.

Today, these age-old practices have been incorporated into their town’s elementary and high school curricula, through the efforts of the tribe, the Department of Education, and civil society organizations.

In this way, future generations of Maeng tribe members learn about their ancestors’ traditions while at the same time protecting the forests and bodies of water that have sustained their tribe for centuries.

The Maeng tribe’s efforts are just one of the strategies being explored by government and IPs in documenting ethnic knowledge on protecting and conserving the country’s natural wonders.

From October 21 to 22, a Pasig City hotel was awash in the colors of the rainbow as leaders from ethnic tribes all over the Philippines gathered to talk about biodiversity conservation issues. (READ: PH natural parks management rated ‘poor’ to ‘fair’)

Around 75% of our key biodiversity areas (KBAs) are part of IPs’ ancestral domains, making IPs frontliners in conservation, said United Nations Development Program Energy and Environment team leader Amelia Supetran.

“Many of their indigenous knowledge systems and practices significantly contribute to rich biodiversity,” said Owen Ducena of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

The government, along with civil society organizations and foreign aid agencies, seeks to document and preserve ethnic knowledge systems and practices to be used in conservation plans for protected areas within ancestral domains.

Because ancestral domains are managed by IPs, getting the IPs involved is crucial for plans to maintain biodiversity and a healthy ecosystem. (READ: New law empowers local communities for ecotourism)

Sense of ownership

Conservation plans should come from the indigenous peoples themselves, based on ethnic practices that they themselves must document, said Ducena.

The plans, called Community Conservation Plans (CCPs), are part of a larger plan that encompasses not just the protected area but the entire ancestral domain. This larger plan is called the Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan or ADSDPP.

Of the 1,071 identified ancestral domains in the country, only 112 have an ADSDPP, according to NCIP. Even fewer have CCPs.

Despite this, there are already examples of successful CCPs.

The Menuvu tribe who live in Balmar at the foot of Mt Kalatungan Natural Park in Bukidnon, Mindanao, were able to come up with their CCP and present it to both the local government and the park’s Protected Area Management Board (PAMB).

Because of this, their CCP is being implemented by the tribe in harmony with the government’s Protected Area Management Plan, said Menuvu tribal leader Datu Alfonso Tumupas.

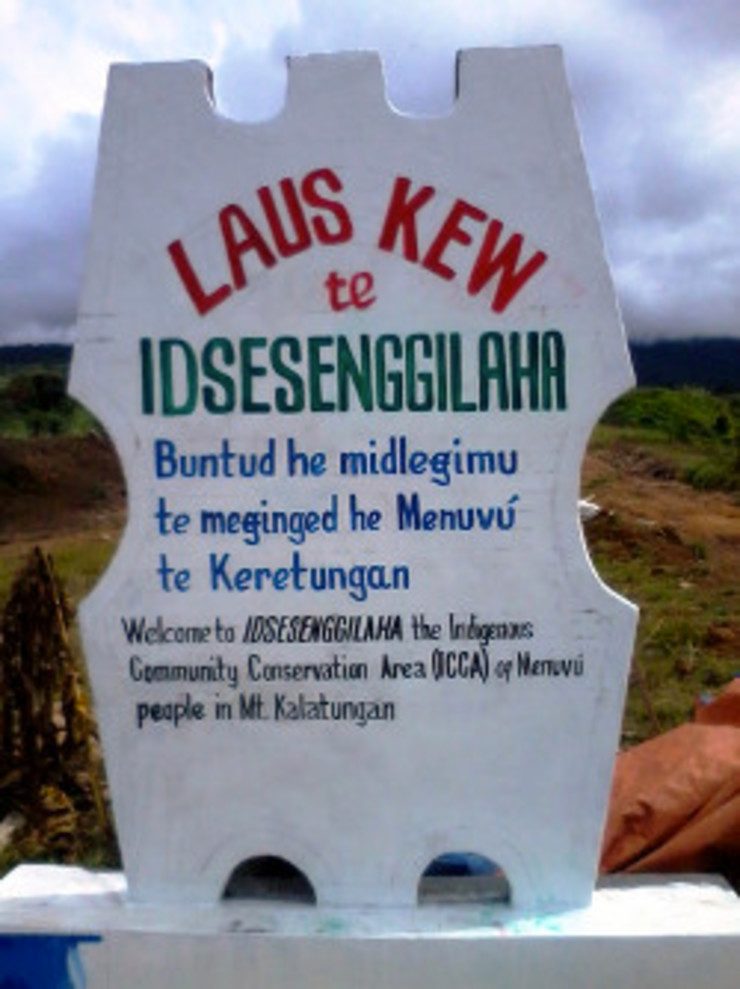

The Menuvu’s Yutang Kabilin, their word for ancestral domain, includes 13,000 hectares of protected area. They also have their own term for the protected area they watch over: Idsesenggilaha.

The Higaunon tribe in Claveria, Misamis Oriental, have also successfully institutionalized their conservation practices.

In their ADSDPP, they created their own group of forest guards, called Bantay Kalasan, to protect the Balatukan Mountain Range, a protected area inside their ancestral domain.

“The DENR trained us on how to guard our forests. We wouldn’t have been able to sustain the Bantay Kalasan without the help of the local government,” said Erlinda Malo-ay, chairperson of a Higaonan tribal council.

Since 2011, monthly honorarium and support for the Bantay Kalasan has been included in Claveria town’s budget. The town also provides the forest guards with raincoats, boots, and flashlights.

The town has just as much interest in protecting the mountain range as the tribe, said Malo-ay.

“The water that flows from Mt Kalatungan and Mt Sumagaya goes to the Cabulig River which benefits the townspeople downstream,” she said.

The mountain range, which acts as a watershed, also supplies water to resorts, hotels, and the Cabulig Hydroelectric Power Plant. The degradation of mountain forests, already happening due to illegal settlement in some areas, will threaten the ability of the watershed to generate water.

Tied to the land

But the project is threatened by the same problems which hound even the more basic initiatives for IPs in the Philippines.

Almost a decade after the passage of the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA), rights of IPs to their ancestral domain remain tenuous in places where local government and corporations want to use the land.

In Mindanao, IPs say they are weary of a growing threat: the use of their ancestral domain for palm oil plantations.

Overlapping land titles pose another obstacle. Lands claimed by IPs as their own are also being claimed by agrarian reform beneficiaries or private individuals who also have their own supporting documents.

Not all ancestral domains are legally recognized by the government through the issuance of a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). Of the 1,071 identified ancestral domains in the country, only 166 or 15% have CADTs.

Even for ancestral domains with CADTs, weak IPs and weak government agencies are unable to monitor or act on cases of trespassing or exploitation of natural resources.

No wonder many IPs want recognition of their ancestral domain as protected areas. Aside from protection under IPRA, that part of their domain at least would get protection from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

Anyway, IPs are often the best conservationists, said many IP leaders. Most, if not all tribes, share the practice of selective cutting in which parts of their forest are dedicated to cutting for timber, gathering for medicine, burial, and worship.

But most importantly, IPs are ideal conservationists because they are tied to the land in ways other people are not, explained Datu Migketey Saway of the Talaandig tribe in Bukidnon.

“Because it is rooted in our life. If you kill nature which is being conserved by the IPs as the foundation of how they embody their culture, the IPs will also disappear. It’s a tandem: life as an IP, our cultures, our tradition, and the integrity of the ecosystem itself.” – Rappler.com

Ifugao woman image from Shutterstock

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.