SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

NEW YORK, USA – When you hear that someone has tuberculosis (TB), you might instinctively distance yourself from that person, fearing that you would be infected. Or you may inadvertently size up the person to see if they bear any signs of being dirty or poor.

TB, a bacterial infection that primarily attacks the lungs, is wrapped in negative stereotypes and taboo.

Public health advocates and TB survivors say that the pervasiveness of these discriminatory misconceptions contribute to TB being the world’s largest infectious disease killer. Every day, TB claims an estimated 4,500 lives. In 2017 alone, about 1.7 million people died from TB despite the disease being preventable and curable.

At the first ever United Nations High-Level Meeting (UN HLM) on TB last September 26, hundreds of public health experts, advocates, and researchers came together to call on all the UN member countries to come together and agree to put an end to TB.

The meeting resulted in the signing of the first ever political declaration which outlined a coordinated global response to TB.

The loudest of voices came from the TB survivors themselves who wanted to change the constricting and discriminatory narrative TB is embedded in by sharing their own personal stories.

By putting a human face to the untold suffering of TB, they called for urgency, political commitment, resources and mostly compassion needed to end TB.

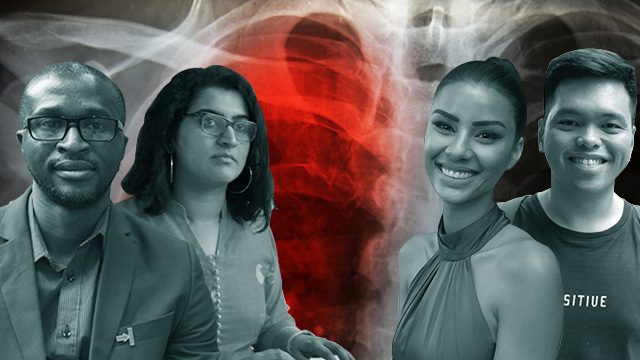

Jeffrey Acaba

NGO worker

Philippines

Jeffry Acaba was exposed to TB at the age of 20, when he was taking care of his grandmother who had contracted TB.

“There is no preventive therapy for TB. The doctor just told me I was exposed to TB – I had scarring in my lungs – but it was ok. There was not much that could be done,” Acaba recalled.

In about 20% of people exposed to TB, the disease can stay dormant for years (also referred to as “latent” TB), and they may avoid developing an active case of TB. However, in some cases like undergoing chemotherapy or having a compromised immune system, latent TB can progress to active TB. This is what happened to Acaba.

His TB was reactivated when he was diagnosed with HIV in 2011. A person living with HIV (PLHIV) is estimated to be 20 to 30 times more likely to be infected with TB.

Acaba was immediately treated for TB and underwent treatment for 6 months.

“The first two weeks were intensive,” Acaba shared.

He was taking 4 drugs, and his body went through a battery of side effects: night sweats, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. “It was easier for me to adjust to my HIV anti-retroviral medicine than my TB meds.”

But Acaba still considers himself lucky. As a virus, HIV works by weakening the immune system’s ability to fight off infections. TB is the number one co-infection of PLHIV.

During this treatment, Acaba had to wear a high grade N-95 mask. Some people avoided him or changed seats so they wouldn’t have to sit next to him in a public transport vehicle.

“I didn’t experience any of that kind of ‘segregation’ at home. I am thankful that my family was supportive and took care of me during my treatment,” he said.

But at the same time, Acaba, now 33 years old, reflected on that period and wondered if it could have been a time to educate his family, relatives, and friends to be more aware of preventive measures to avoid getting TB.

At the UN HLM, Philippine Health Secretary Francisco Duque III committed that the Philippines will do its part to end TB worldwide by targeting to treat more than 2 million people with TB. (READ: U.N.’s high-level meeting on TB: Why the Philippines should care)

Acaba, in his role as a program officer for regional civil society organization APCASO, took an active part in drafting the civil society response to the UN’s political declaration.

As a regional body that advocates for public health approaches that are framed around a human rights approach, APCASO highlighted that the role of civil society – much like the role of family and loved ones – is an essential part of TB care.

“I hope that we can scale up isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) in the Philippines,” Acaba said. (READ: Philippines joins countries in committing to end global TB epidemic by 2030)

IPT therapy is shown to be highly effective in preventing latent tuberculous infection from progressing to active TB.

“There are many people exposed to TB in the Philippines and have latent TB. There is much that can be done before it develops to actual TB. The medicine is free. The government just needs to promote it more,” Acaba said.

Tamaryn Green

Miss South Africa 2018

South Africa

Tamaryn Green was a third year medical student in Cape Town, South Africa, when she was infected with TB.

She started treatment immediately but did not tell her extended family or friends about her condition, fearing she would be treated differently and isolated by others.

In her second month of treatment, it became too much for her and she spoke to her professor who got her help from a specialist doctor. Her university was very supportive and offered her counselling. She contracted hepatitis as a secondary infection and felt ill every day for a month. She moved back home, changed her medication, and soon felt better until she was eventually cured.

She described the experience as “more traumatic than I ever allowed myself to admit. It not only affected me but also my immediate family and close friends.”

Now, Green wants to use her stature and platform as a beauty queen to draw more attention to TB and get more people talking about it through her #BreakTheStigma campaign.

“TB is not spoken about enough. We need more attention drawn to the issue. Treatment is given but not enough counselling around the disease and importance of adherence is done. Access to health facilities are not always possible for many people. This prevents diagnosis, follow-up is often lost, and people never get their diagnosis and treatment,” Green said.

“The stigma around TB makes disclosure to families and friends very difficult and often discourages patients attending clinics. There is a lot of shaming and blaming of patients around this disease.”

Among the stigmatizing misconceptions she wants to break is that once you have TB, you are forever contagious.

“This is wrong. TB is curable and once starting treatment, you are no longer contagious,” Green noted.

As Miss South Africa, she is very much aware that she has a platform to speak for those who cannot be heard.

“By speaking up, I am showing the world TB can affect anybody and we should not be ashamed of it. I want to take that message internationally using the Miss Universe platform at the end of the year,” she said.

“I am in a position where people are looking to me and listening to what I have to say. I must utilize this opportunity to help others.”

Abdulai Sesay

Representative, Affected Communities High Level Meeting Advisory Panel

Sierra Leone

Abdulai Sesay never considered himself a human rights activist until he survived TB.

Sesay was working on gender-related issues in Sierra Leone when he first got sick. He went to see a herbal doctor because others thought he had been hexed with a spell.

It took 6 months before he was diagnosed with TB. By that time, he had been isolated and shunned by his family and his community.

“I lost my job and I was thrown out of my house,” he recalled.

When he lost his job, his kids had to drop out of school because as the family breadwinner, he could no longer pay for their tuition. Later, his wife left him and he lost custody of his children.

“I started blaming myself and the health system. Why did it take so long for me to be diagnosed for TB?” he said.

Now, as an advocate and survivor, he wants to make the voices of TB survivors heard so people will understand how the disease affects more than just the person living with TB.

“TB is a security issue. When you look at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, you realize that Article 1 talks about how quality healthcare should be affordable and accessible. My right to that was violated,” Sesay said.

“We really need to put a human face to TB. Let’s develop policies at top level. Let us remove barriers to TB services and implement them at the community level. There is no social support for people affected by TB, and that needs to change. It is not a poor person’s disease. Two members of parliament from Sierra Leone had TB.”

Rhea Lobo

Journalist, filmmaker, motivational speaker

India

One of the first things that the doctor treating Rhea Lobo asked her was, “How did you get TB? It is a poor man’s disease.”

That was the one of the many metaphorical slaps in the face that Lobo received when she was diagnosed with bone TB in 2008.

Though only lung or pulmonary TB is infectious and bone TB, like the one that Lobo was diagnosed with, is not, Lobo found that many people kept their distance from her. Others told her outright that she was less desirable as a woman.

“They told me no one would marry me, and that I won’t be able to conceive,” she said.

India tops the list of 8 countries where more than two-thirds of TB cases were found. An estimated 2 million people in India are infected with TB, accounting for one fourth of the global TB burden.

It took Lobo 4 years to share her story of surviving TB. In this video, Fight TB. Stay Beautiful, Lobo speaks lightheartedly about her experience, saying “Well, who knew? I did get married! Happily married!” slaying the myth that no one would want to marry a woman with TB.

In another film, End the Taboo. End TB., Lobo profiles TB survivors who share intimate stories of how TB affected their lives. One woman survived TB but lost her husband and son to TB because they were misdiagnosed and their treatment was delayed.

The film ends with the strong message that TB is preventable and curable. A major step in fighting the disease is talking about it and ending the myths that surround it – like the persistent one that says TB affects only poor people.

“The books may tell you that TB is a poor man’s disease. The truth is this — the rich are just not talking about it,” Lobo said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.