SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The resurgence of measles in the United States and the UK, a polio outbreak in the Philippines, HPV-vaccine resistance in Japan — these headlines from the past year have roots in global anti-vaccine campaigns that stretch back over 200 years.

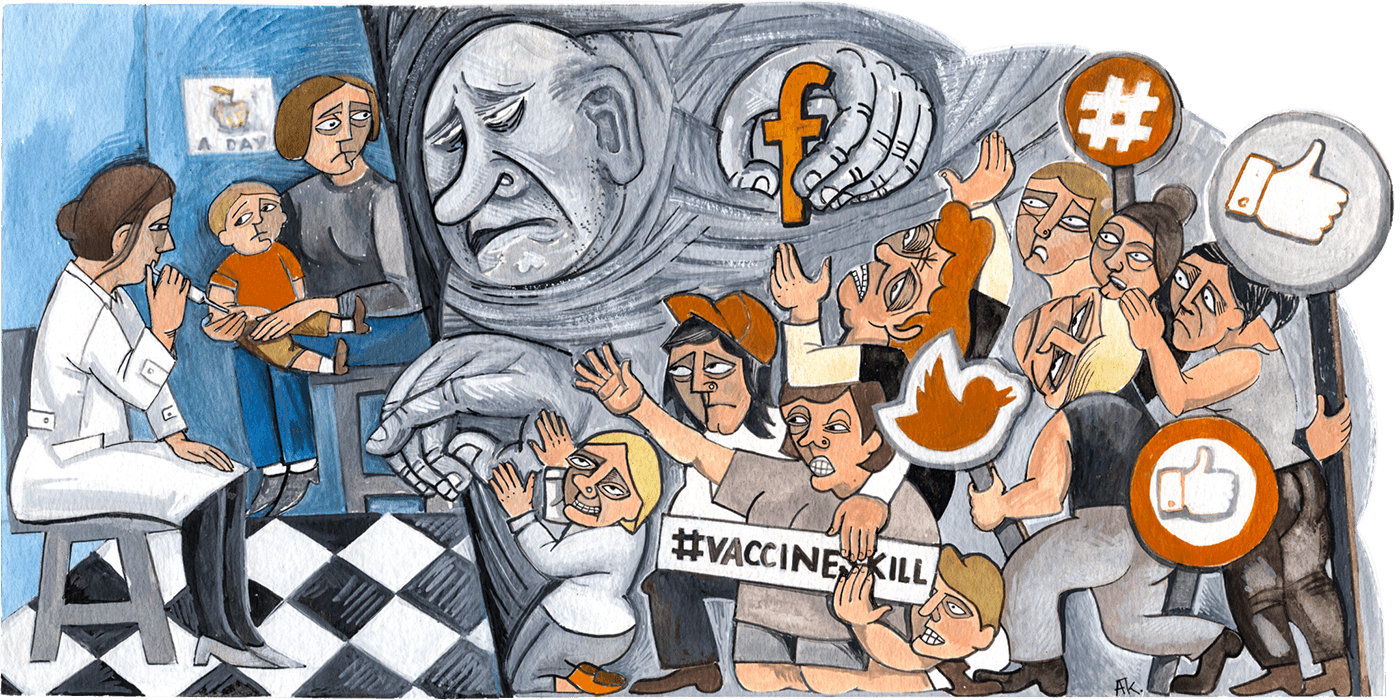

Concerned parents, religious groups, liberals and pseudoscientists alike are adapting the messaging of their anti-vax predecessors for the internet age with alarming success.

Supercharged by social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, the anti-vaccine movement today has moved into the mainstream: last year, vaccine hesitancy was included in the WHO’s top 10 threats to global health.

But the anti-vax movement has been around since the first-ever vaccine, and to understand how we got to today we need to go right back to early vaccine campaigns and their opponents.

Edward Jenner and the rise of the first anti-vax mob, 1790s

Smallpox roamed Europe in the 18th century, killing close to half a million people each year. For centuries, people had been searching for a cure to the disease, known as the “speckled monster.”

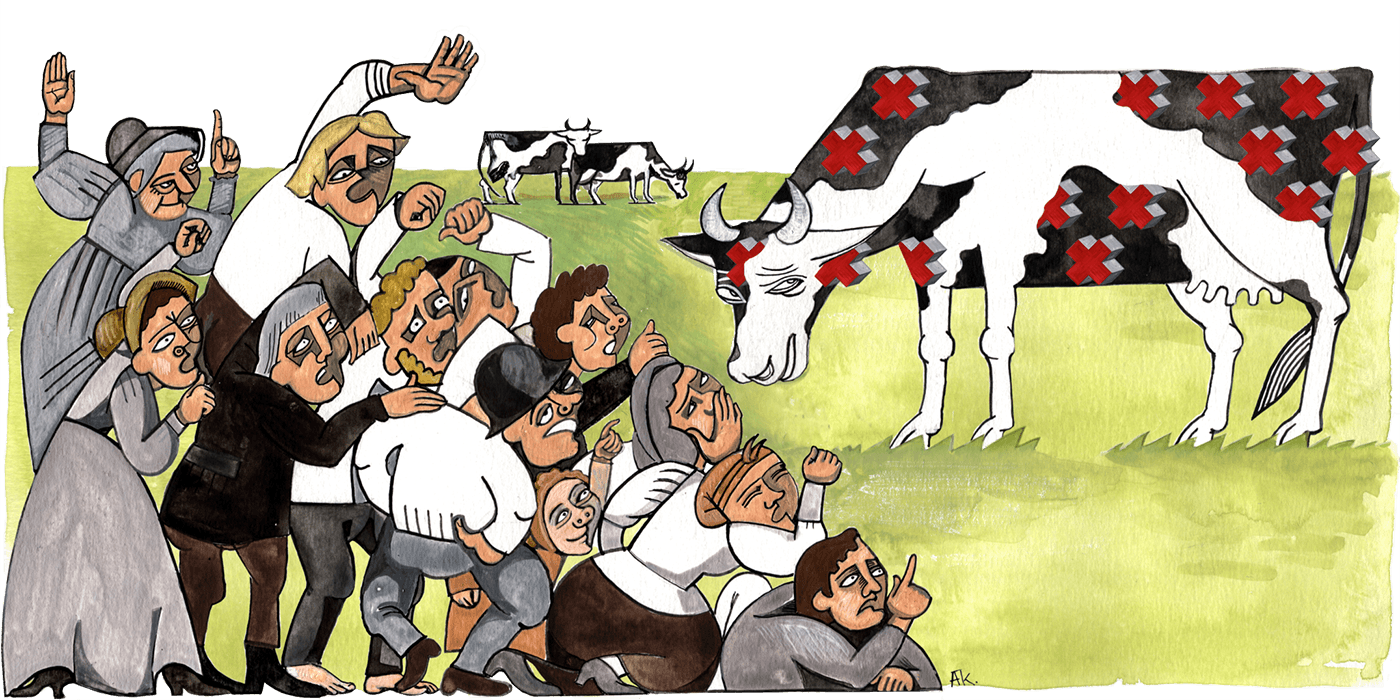

In 1796, English doctor Edward Jenner began experimenting by injecting people with a small amount of cowpox, a milder version of the disease, to make them immune to smallpox.

Jenner experimented on several other children, including his own 11-month-old son, and proved that inoculation with cowpox made children immune to smallpox. The word vaccination was coined for describing immunization, originating from the latin word “vacca” (cow).

News of the vaccine outraged clergymen and doctors alike who demanded a halt to injections. People would turn “bovine,” or cattle-like, they said. When no bestial, cow-people materialized, they argued the vaccine refuted God’s will. From the outset, religious conservatives have formed an active base of the anti-vaccine movement.

The anti-vaccination movement mobilizes, 1850s

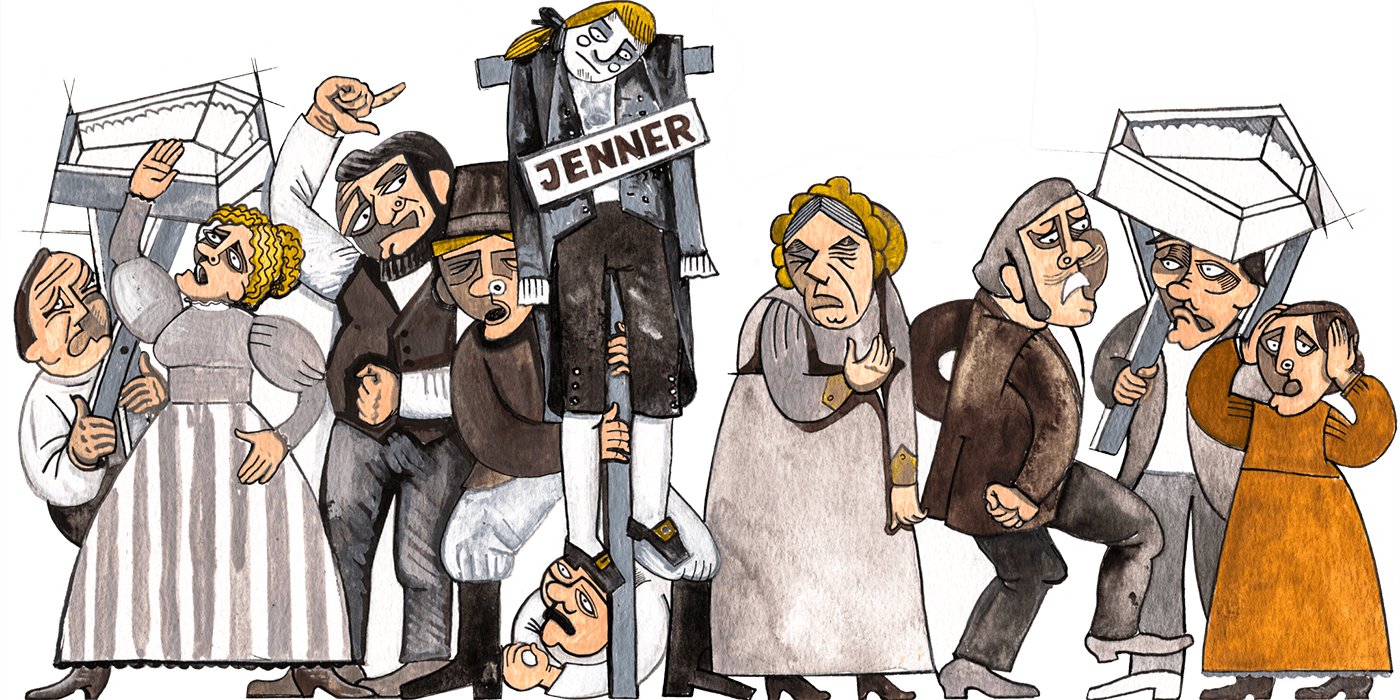

Once vaccines against smallpox became compulsory and routine in England in 1853, anti-vaxxers formalized their resistance with anti-vaccination leagues. In the 1850s and 60s, the movement spread beyond anti-vaccine doctors and the clergy.

Tens of thousands of people marched through the city of Leicester, England in March 1885, bearing child-size coffins and an effigy of the English doctor Edward Jenner.

One prominent British anti-vaccine activist, William Tebb, traveled to America in 1879, to campaign against vaccines. He would influence how early anti-vaccination societies were established in the U.S.

Anti-vaxxing by way of civil rights

By the second-half of the 19th century, smallpox rates were on the rise in the U.S. in part due to the early successes of organized anti-vaccination leagues who pushed a number of states to repeal compulsory vaccination laws.

As the popularity of the leagues grew, some prominent defenders of civil liberties such as Frederick Douglass joined the objection to mandatory vaccination programs by arguing they encroached on people’s liberty and freedom of choice.

Finally, a case in Massachusetts reached the Supreme Court in 1905 after the state fined Henning Jacobson, a resident of Cambridge, for refusing his smallpox vaccine shots and Jacobson appealed to the Supreme Court.

At the time, the law required all adults to get a second smallpox vaccination or pay a $5 fine. Jacobson and his son had suffered severe reactions to previous smallpox vaccinations and he argued that genetic predisposition placed him at risk if he were revaccinated.

The court ruled that ultimately individual states would decide which mandatory vaccination laws and exemption regulations to pass. The court also granted individual state governments the authority to enact laws that were necessary to protect public health and safety.

The Cutter Incident, 1955

The American fear of polio was “second only to the atomic bomb” during the post-war period, according to one prominent advocate of vaccination. In 1955, more than 200,000 children in five U.S. states were inoculated against polio as part of the country’s first mass vaccination program against the disease.

But it was later discovered that some lots of the vaccine, produced by a pharmaceutical company called Cutter Laboratories, accidentally included traces of the active virus, leading to 40,000 new cases of polio. The company withdrew its vaccine from the market, but later investigations revealed that scores of people had been paralyzed and several died.

The Cutter incident’s legacy sowed distrust in the newly discovered vaccine for years to come. Mass litigation followed and many pharmaceutical companies at the time permanently abandoned vaccine production. Today there are only a handful of pharmaceutical companies distributing vaccines in the U.S.

A new vaccines study is published, sparking a new anti-vax narrative, 1998

Anti-vaccine health scares have also originated from the field of medical sciences. Andrew Wakefield, now a discredited physician, and his colleagues published a study in the British medical journal The Lancet, suggesting that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine, given to children around the age of 18 months and again at four years, could lead to autism. While it later emerged that the research was flawed, the study had already become a disinformation bomb. Two decades later, anti-vaxxers’ belief in Wakefield’s study persists.

“Public confidence in MMR and vaccination has never fully recovered,” wrote Seth Barkley, chief executive of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Wakefield was eventually struck off the medical register in the UK and went to the U.S., where he directed an anti-vax documentary “Vaxxed” aiming to “out” an alleged Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cover-up of the MMR vaccine’s side effects. President Donald Trump has promoted Wakefield’s findings on Twitter.

HPV vaccine is recast as promiscuity promotion, 2010s

In 2007, countries around the world launched a new vaccines program to protect against the sexually-transmitted human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes certain types of cervical cancers. The vaccine was primarily given to teenage girls.

From the outset, some conservative religious groups rallied against HPV vaccines, arguing it would encourage sexual promiscuity. “It’s basically a sex jab, encouraging the view that girls can be sexually available,” said Colin Hart, director of the Christian Institute Charity in the UK, to the London Telegraph at the time.

As the anti-HPV campaign gained traction, unease about the vaccine’s safety spread through countries in waves. In Denmark, Japan, Ireland and Colombia, vaccination rates plummeted after media outlets in those countries circulated unfounded claims that the vaccine was causing a wide range of health complications and disabilities.

While those claims have been debunked, HPV vaccine rates in Japan and Colombia still remain below 5%. Last year CDC reported a small increase in HPV vaccination uptake in the U.S. compared to previous years, but numbers still lag behind other vaccines recommended for teenagers.

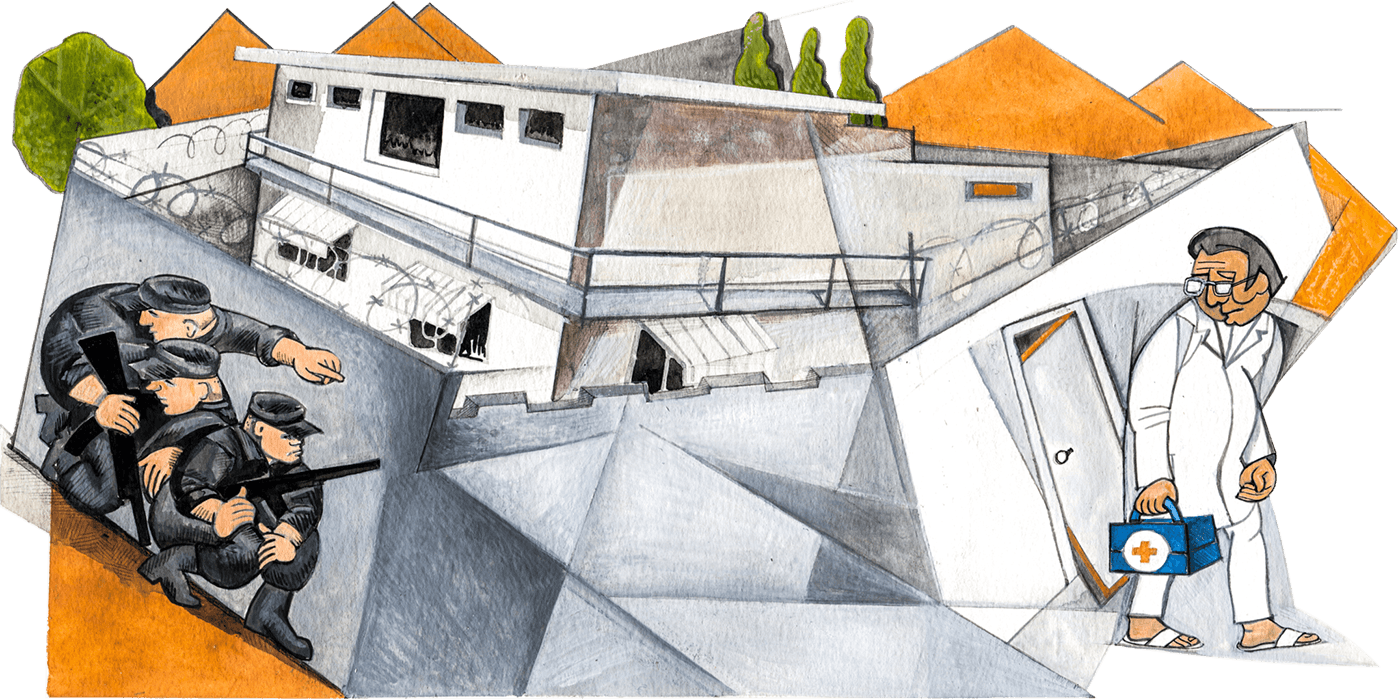

Aftermath of Osama bin Laden’s death drives polio surge in Pakistan, 2011

The US mission to track down al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden featured a Pakistani doctor, Dr. Shakil Afridi, who began vaccinating people against hepatitis B in Abbottabad, Pakistan in 2011. Afridi’s vaccination drive was part of a CIA attempt to gather DNA from the residential compound where bin Laden was suspected to be hiding.

In the aftermath of bin Laden’s death, Afridi’s role outraged many Pakistanis and he was given a jail sentence of 33 years by a tribal court. The Pakistani Taliban used Afridi’s role in bin Laden’s death as an opportunity to aggressively push anti-vaccine propaganda, accusing health workers of espionage. The following year, 70 health workers were killed and harassment of medical staff continues today. In 2019, Pakistani authorities were forced to suspend anti-polio campaigns, as health workers continued to be attacked.

The surge in polio cases in Pakistan is one of several examples where ultra-religious and populist groups can antagonize vaccination campaigns — similar scenarios can be seen in Nigeria and Italy.

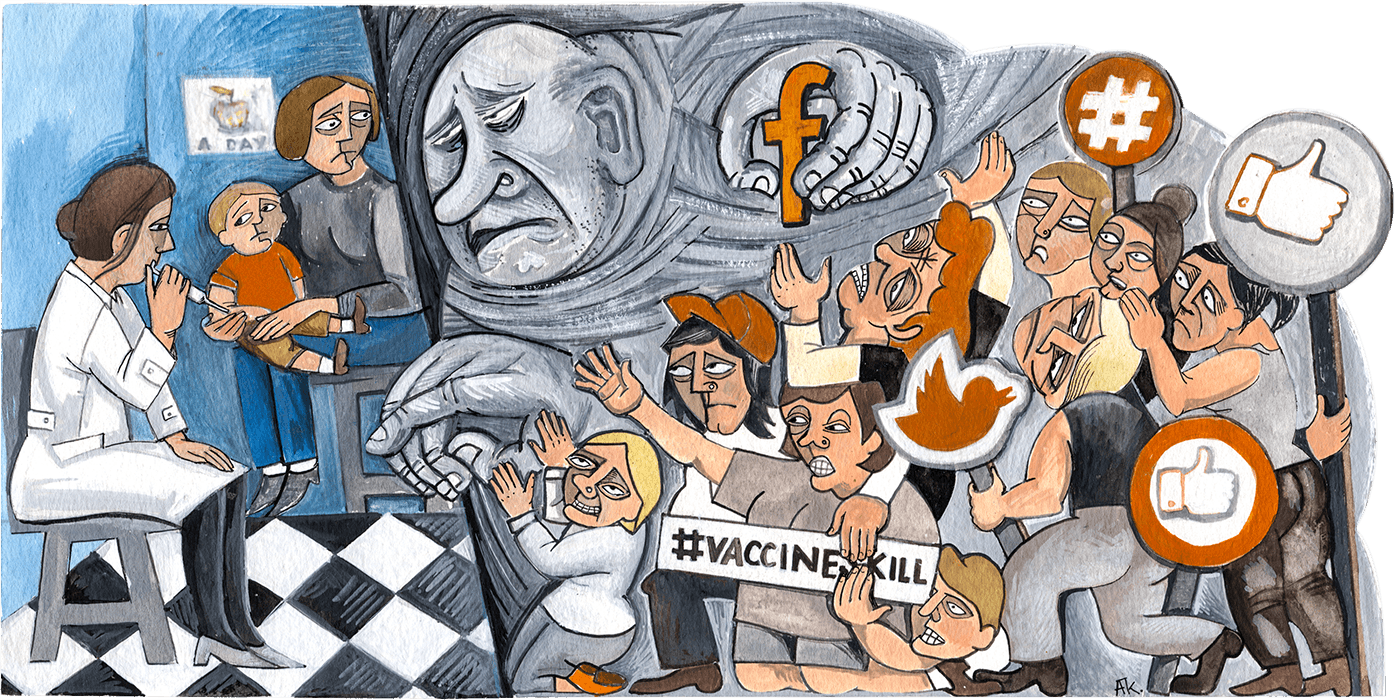

Social media supercharges anti-vax messages as infectious diseases re-emerge

In today’s age of social media, anti-vax messages are easily shared on platforms like Instagram and Facebook. “In many respects, anti-vaccine messaging hasn’t changed substantially since the era of Jenner,” explained Dr. David Robert Grimes, a cancer researcher and physicist at the University of Oxford.

Anti-vaxxers have skillfully exploited social media platforms and closed messenger groups at an alarming rate. Anti-science messaging and a growing distrust of state institutions have also aligned with the output of bots and Kremlin propaganda which seek to sow distrust and fear. Social media platforms like YouTube and Instagram have been accused of amplifying anti-vaccine content over science-based material.

Last year, a number of countries saw new measles outbreaks and there has been an increase in the number of people infected in countries that were previously regarded as measles-free, including the U.K and the U.S. – Rappler.com

With additional reporting by Isobel Cockerell. Mariam Kiparoidze is an associate producer at Coda Story.

This article has been republished from Coda Story with permission.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.