SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – We have an ugly plastics situation.

The Philippines is the third biggest source of plastic leaking into seas worldwide, just behind China and Indonesia, according to a widely-cited 2015 study on plastic waste.

The study titled, “Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean,” came out 4 years ago, but it appears the situation has remained unchanged, if not gotten worse.

A report from the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) released in 2019 also said that almost 57 million shopping bags are used throughout the Philippines every day, or roughly 20.6 billion pieces a year. The same report said that in just a year, the average Filipino uses 591 pieces of sachets, 174 shopping bags, and 163 plastic labo bags (thin and translucent plastic bags).

The situation is grim, but there is hope. Various advocacy groups in the country have started their own campaigns to raise awareness, while government has also taken steps through some legislation.

At the individual level, one movement often mentioned in plastic pollution campaigns is the zero waste lifestyle.

What is zero waste?

The term has been around since the early 2000s, but it gained more popularity starting 2010.

In 2013, it turned into a global movement after renowned blogger Bea Johnson released her book, Zero Waste Home, that year. She wrote about her family’s astonishing lifestyle transformation that saw a radical shift from a hyper-consumerist lifestyle to a much simpler one. They managed to reduce their year’s worth of combined garbage to only one liter – just enough to fit a mason jar. (READ: How to start a Zero-Waste Lifestyle)

How did Johnson do it? By following the 5 Rs method – refuse, reduce, reuse, recycle, rot – which many of the zero waste enthusiasts, including those in the Philippines, have adopted.

This gave the zero waste lifestyle a more personal meaning because it showed that it was something that one person or even families can aspire for – beyond the usual recycling and waste management.

Zero waste lifestyle: A personal battle

Monique Obligacion, community administrator of the Buhay Zero Waste group on Facebook, said that zero waste as a practice means aiming to produce as minimal waste as possible in our everyday lives such that not even enough would be left for recycling.

“Recycling is really not enough. It’s not gonna do much because in the end, it’s still going to turn into trash,” Obligacion said. “All these shampoo bottles, [they] recycle them into a chair. When a chair breaks, how are you gonna recycle it? It’s very finite and it’s a very labor- and energy-intensive process, recycling.”

There are many ways to achieve zero waste. Because the movement is considered a lifestyle, Obligacion said it can involve purchasing eco-friendly alternatives, growing food, or even choosing sustainable clothing and fashion.

Discussions in the Buhay Zero Waste group mirror personal experiences of members, such as their first time to bring their reusable containers to the market and letting other members know which milk tea and coffee shops allow reusable tumblers.

“Going zero waste is a personal journey,” said Meah Ang See, one of the group’s moderators.

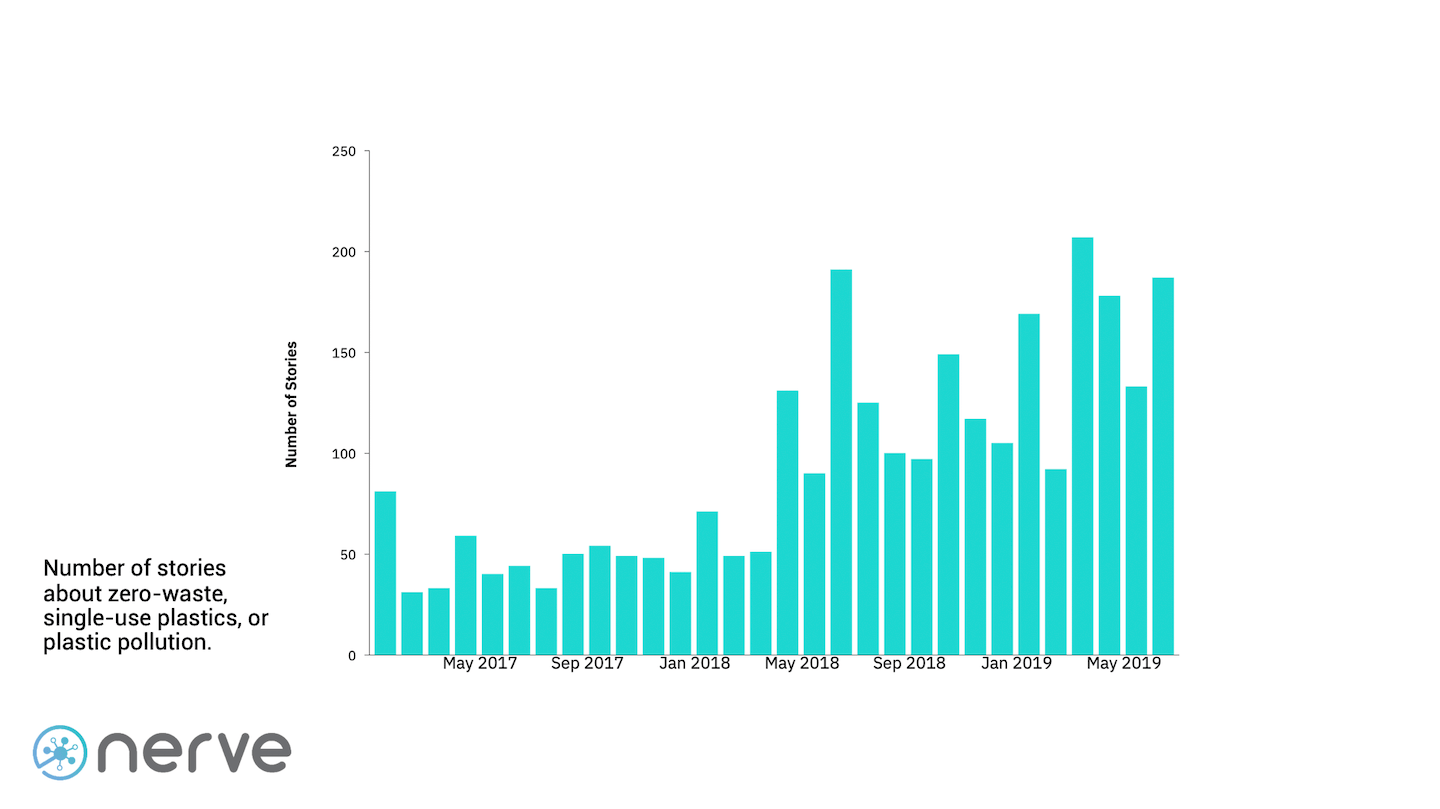

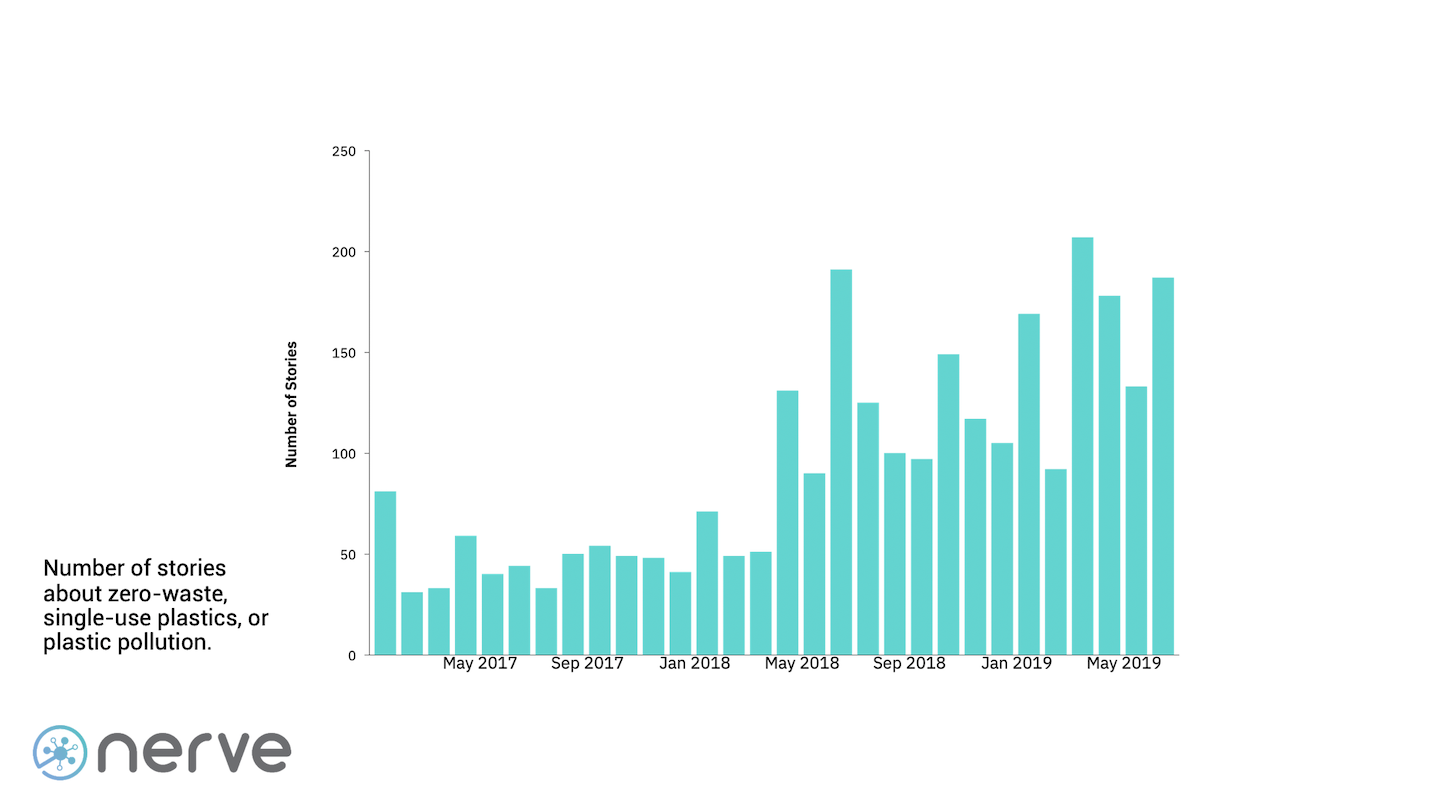

Buhay Zero Waste is a thriving online community that has over 43,000 members on Facebook as of early September 2019. It is the biggest online group on the social networking site that discusses the zero waste movement in the country. But the movement only started to gain wide popularity in late 2018 up to 2019 as seen in their Facebook group’s engagement.

Obligacion, meanwhile, has been involved in the movement since 2016. She acknowledged that back when the movement was still gaining ground in the country, the conversations were still focused on plastics and recycling. But soon enough it hit her, “It should be just not having anything to recycle in the first place.”

For her part, Obligacion said she has learned how to grow her own food and bake her own bread to address the issue of food waste. She also no longer sends her non-biodegradable trash to landfills – all in the name of sustainability.

Elitist?

Individuals promoting zero waste all have good intentions, but their efforts have been criticized as being somehow “elitist,” given the calls to refuse plastics altogether and to replace them with eco-friendly alternatives instead.

A scan of Twitter conversations on zero waste from January 2018 to August 2019 shows that the most discussed topics were about straws and shopping for zero waste. This alone suggests that public perception of the movement is consumerist, where purchasing alternatives was needed to become part of the movement.

Rocco Mapua, Obligacion’s partner and a fellow advocate of the movement, said this should not be the case.

“With the way things are right now, we are such a consumerist society. When you step out of the house, and everything is telling you, ‘Buy, buy, buy, buy, buy.’ So what we try to tell them is that there are things that you don’t need to buy,” he said.

In fact, there are studies that suggest paper production causes more harm to the environment than plastic production in terms of water and carbon footprint.

This does not mean that one is better than the other; it’s just that while plastics are seen as more harmful in the downstream of disposal, paper alternatives contribute no less damage to the environment through their production. (READ: [OPINION] Paper vs plastic: The right choice might not be what you think)

For Obligacion and her group, however, the conversation shouldn’t be centered on this debate. What people seem to forget is that the zero waste movement’s point is the reduction of waste by avoiding purchases to begin with – the first R in Johnson’s 5-point tenet: refuse.

What is government doing?

In 2000, the Philippine government passed Republic Act No. 9003, also known as the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act. It serves as landmark legislation for managing waste in the country, right from its inception to its final disposal.

Local government units (LGUs) are tasked to craft their own local solid waste management plans under this law, which the National Solid Waste Management Commission (NSWMC) is mandated to review and oversee. This refers to each LGU’s framework for reusing, recycling, and composting wastes generated in their jurisdictions.

However, as of May 2019, only less than half of all LGUs in the Philippines (41.96%) have NSWMC-approved 10-year solid waste management plans.

Data from the NSWMC shows that out of all the regions in the country, only Metro Manila has a 100% rate of approved solid waste management plans. The Bicol Region is last, with only 3 of its 114 LGUs having such plans.

It’s no different in terms of local plastic regulations. (READ: Why can’t the Philippines solve its trash problem?)

News reports and information on LGU websites say that as of August 2019, there are only 65 cities and municipalities in the Philippines that have enforced ordinances prohibiting and/or regulating the use of plastics. Majority of these LGUs are in Luzon, particularly in Metro Manila.

At the national level, at least 29 bills that have been filed in the 18th Congress – 7 in the Senate and 22 in the House of Representatives – propose to ban or regulate plastics. Sadly, no bills have been filed for the development of the zero waste system in the country, aside from those addressing food scraps.

Still, the government has exerted efforts to introduce the zero waste concept in the country. In 2014, January was declared the Zero Waste Month through Proclamation No. 760.

Since then, the NSWMC, together with other government offices, government-owned-and-controlled corporations, and even non-governmental organizations have organized activities and events to educate the public about effective waste management every January.

But zero waste is certainly more than just solid waste management and plastic bans, as advocates have shown.

The role of corporations

If individuals and government have roles to play, so do corporations.

For instance, the country’s “sachet culture” cannot be ignored when it comes to zero waste. In the Philippines, tingi or products in small packages are sold to low-income markets because this gives them the ability to buy everyday necessities in small quantities.

The 2019 GAIA report on waste assessments and brand audits shows that more than 50% of all plastic residual waste collected were “branded waste.” Of this, only 10 companies were found responsible for 60% of all the branded plastic waste collected from the study sites.

International non-governmental organization Greenpeace, for one, called out the corporations and demanded accountability for all the plastic pollution they’ve caused. Their message is clear: to address this plastics problem, it should be stopped right from its production. (READ: The problem with plastics: stopping it ‘at the source’)

In contrast, individuals in the Buhay Zero Waste are less predisposed to finger-pointing. “For us, for people who practice zero waste, we take the responsibility upon ourselves for the waste that we generate and the things that we buy. I think not just downstream of my disposal, but also upstream of my purchase,” Obligacion said.

This does not mean that the group absolves multinationals from blame. It just means they are more open to collaborate and think of other ways to approach the situation.

Though rather small compared to the government and advocacy clusters, in recent years, companies have also taken a more active role in trying to include sustainability in their business activities. Corporations have launched initiatives to create louder buzz in the media to raise awareness about zero waste.

“At least all these big corporations are starting to clamp down on that stuff, whereas before it’s like they just churn these things out,” Obligacion said, adding that they consider this as a win for the movement, no matter how small.

In the country, the top 5 companies that have published the most number of articles and press releases discussing their sustainability and zero waste efforts are The Coca-Cola Company, Starbucks, Nestlé, Unilever, and Adidas. Their campaigns range from pledging to make the packaging of their products recyclable, hosting events to raise environmental awareness, to building facilities that process their post-consumer waste.

This positive response is why Obligacion and the Buhay Zero Waste community choose not to attack the corporations.

“[If] you start attacking somebody, they’re really not going to work with you anymore. They’re not gonna want to learn from you or listen to you even. So it’s better to just keep talking about what we do, telling them what we want, so that they know what we want and they can adapt accordingly,” Obligacion said.

While there is no one surefire way to address the worsening plastic pollution in the country, what’s important is that different sectors have their own acts in place. The problem is a complex one that needs attention from the government, companies, and individuals themselves. – Rappler.com

With contributions from data insights company, TheNerve.co (Topic mapping by Don Kevin Hapal, mapping of zero-waste ordinances by Angelica Sinay and Ralph Nodalo).

Rappler is building a network of climate advocates, LGUs, corporations, NGOs, youth groups, and individuals for the #ManyWaysToZeroWaste campaign, a movement pushing for responsible ways to use and reduce plastic. Go here to know how you can help.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.