SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Most people think those in the sciences are smart because they know stuff. But what the people in the sciences really possess is a stable relationship with “uncertainty” than those who are not in the sciences.

“Uncertainty” is not knowing nothing but accepting that we can only know so much from science at a certain time and that current knowledge can be modified, or even reversed depending on new evidence. This way, scientists remain open to changing their minds if the evidence compels them to do so. If they did not change their minds despite new evidence, then we should all pack up and resign to our fate.

And having evidence is not a quiz. It is a process, often a long and tedious one not only because of the availability of funding or materials, but also because of the specificity of the science (they study certain aspects only at a time to make sure they are really focused on the effects of the aspect they are studying) and reliability of the samples. You have to have a valid sample size relative to the potential affected number to generalize for larger populations. They also have to cross-check that with related tests or similar tests. This takes a lot of time.

As of March 12, at least 900 scientific papers have come out on the novel coronavirus but none of these, on their own, have led to a treatment, cure or vaccine for now. These studies have to bear on each other, and more studies to test, to lead to those. This virus is NEW, and science is doing a parallel course of getting to know it while fighting it. Which is a very tricky thing.

This is what is frustrating many people about much information, including our own health authorities, in giving guidelines to the public based on scientific evidence.

Here are 3 guideposts as to where we are, so far, in terms of what science has told us and how we can think about it knowing that the information can change:

1. Why does this novel coronavirus seem to be especially nasty to humans?

So far, scientists have found that the virus finds something inside our bodies that it can easily hook itself onto.

The spikes (the virus belongs to a family of viruses that are round with outer spikes, thus they named it “coronavirus”) in this novel coronavirus seem to have a protein that latches on to an enzyme called “furin” found in many of our organs – lungs, liver, small intestines. They suspect that this explains, if not wholly but in part, why the virus spreads so much more than the SARS.

Another study has found that the spikes also get attracted to something found in human cells nicknamed ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 at least ten times more tightly than does the spike protein in the SARS virus.) They want to be sure if these are the only ways that this novel coronavirus inserts itself in our bodies so they can find ways to cripple its modus operandi.

How we can think about this: This grounds our deepest hopes on an effective treatment or cure.

While most of us are working out how to be sane and stable in a lockdown, scientists are hard at work so they can figure out the treatments or cures to block the work of this virus. This assures us that science is not sleeping and is focused on the deep mechanisms of how this nasty virus is invading human cells.

While you are at it, it also gives you a glimpse at how science is crucial in solving the greatest problems of our time. Cultivate an appreciation for science, now, more than ever so you could see how it can help the way we work (regardless of what your job is), educate our youth and support the science being carried out by doctors, health workers and researchers not only during a pandemic but all the time.

2. Aren’t other viruses so much worse but we have managed to keep them at bay?

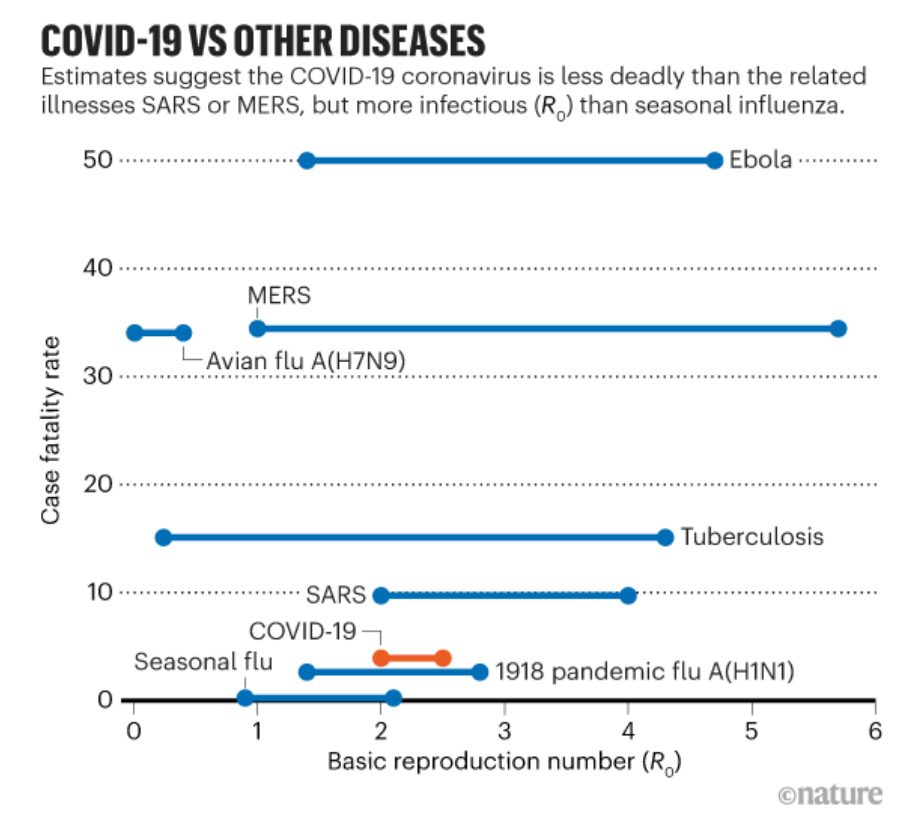

Here is the latest figure from the journal Nature on how COVID-19 is in terms of fatality rate and reproduction compared to related outbreaks.

It is definitely more than the seasonal flu in terms of fatalities but yes, SARS, MERS, and Ebola are far worse but those outbreaks have been contained. This is a new coronavirus and as mentioned in #1 above, we have not been able to contain it, that is why we have a pandemic.

How we can think about this: As citizens, we cannot shrug off COVID-19 because we survived the Ebola, MERS, and SARS outbreak. COVID-19 is much faster in the way it infects. The rate it will infect humans depend on us. This is why we have to stay home, so that the virus eventually runs out of a critical number of hosts to invade.

3. Is it airborne or not and therefore, should we wear masks or not?

It seems that the confusion on whether it was airborne or not was mainly because of 2 things:

- Using “airborne” will cause more panic and deprive health workers of their essential masks; and

- Experts themselves cannot agree on one definition of “airborne.”

We will never get a consensus because “airborne” means different things to experts. Some of them think of it as just being “transmissible by air” while others qualify under what conditions it is transmissible by air – which in this case is coughing, sneezing, talking, or even breathing.

How we can think about this: The coronavirus does not differentiate which definition of “airborne” you accept before it enters you. Therefore, if you breathe, you may be carrying it with or without the symptoms, then just consider it “airborne” and wear a mask even if you cannot get hold of a N95 mask. This empowers the citizenry to innovate and help each other.

All the expert definitions, including that of WHO in a press conference I have come across before I wrote the column saying that it is airborne, all point to transmission being “airborne.” They have qualified it as I have because a word cannot describe all its real-world nuances. So when health authorities were insisting it is not “airborne” but say that the new coronavirus means that the droplets that carry the virus from infected people can be expelled by people by coughing, sneezing, talking or even just breathing especially in confined spaces, then it gets confusing because you know you breathe air.

When it concerns our health and safety, when there is uncertainty, we should err on the side of caution. This means when the experts are not sure, we play it safe and still wear masks. Thinking of it as “airborne” because it can be carried by one’s breath, it now makes sense to wear a mask all the time even when it is not a N95 mask. This is because the droplets could be different sizes and some can be large enough to be trapped by masks before they come out. This matters because the amount of exposure we get from the droplets will determine if we will get sick of the virus or not.

Reasoning in the time of COVID-19

We can live with uncertainty because we have been doing so for the most part without always being conscious of it, with or without the pandemic.

Life is for the most part a journey through uncertainties. This current crisis gives us extra shivers because it is happening to all of us at the same time.

This is why I am wary of “war” being repeatedly invoked as the metaphor to fight this crisis. “War” implies there is a motive behind the enemy. The enemy is not even a living thing. It is an invisible thread of genes that rides on watery bubbles and its nature is to find a host and multiply.

And we humans? Reasoning and kindness have always seen us through the darkest of hours in the entire history of humanity.

For sure, our nature includes panicking and being warlike, but our BETTER NATURE is to rise above the elements of “war” and find the most harmonious way to deal with this – with reason, discipline, a respect for roles, and above all, kindness. – Rappler.com

Maria Isabel Garcia is a science writer. She has written two books, “Science Solitaire” and “Twenty One Grams of Spirit and Seven Ounces of Desire.” You can reach her at sciencesolitaire@gmail.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.