SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “Oh, my God,” then Colonel Avelino “Sonny” Razon Jr muttered to himself on January 12, 1995 as he watched Pope John Paul II walk to a crowd at the Villamor airbase in Pasay City, where his plane landed for his second visit to the Philippines.

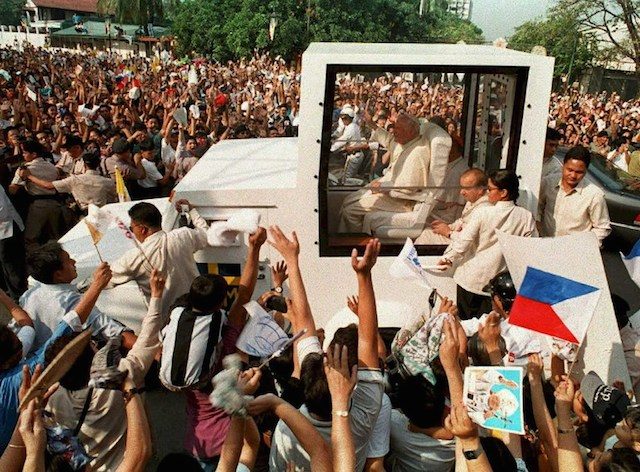

Razon, Presidential Security Group (PSG) officer in charge of the Pope’s close-in security at the time, said the plan was for the Pope to immediately board the bulletproof popemobile as soon as the arrival honors with President Fidel Ramos was over, and proceed to the Papal Nunciature, the residence of the Vatican’s ambassador to Manila.

The VIP guest had other plans, however. He wanted to say hello to the faithful who were waiting for him at the airport.

But why would this be such a big deal to Razon?

On January 6, 1995, a few days before the Pope’s arrival, Razon was looking at a photo of John Paul II tacked on a board in a room at the Doña Josefa apartment in Malate, Manila, which was littered with bottles of chemical bomb components. He also saw a priest’s cassock – a clear red flag to authorities because the two men living in the apartment were from the Middle East.

That fateful day of January, the police uncovered a terrorist plot to kill John Paul II.

Ramzi Yousef’s apartment

As the Philippines made its final preparations for the visit of Pope Francis on Thursday, January 15, Rappler sat down with Razon about the 1995 papal visit. (Eventually becoming the Philippine National Police chief, Razon is now detained at the PNP custodial center over malversation charges filed against him and 32 others, charges that he said he was linked to largely because he was a signatory to certain documents.)

“Sabi ko, iba na ‘to. Kasi ang report mga Muslim ang nakatira. Why would a Muslim have a sutana, a bible, and a picture of the pope (I said to myself, this is different. The report said Muslims lived there. Why would a Muslim have a priest’s cassock, a bible, a picture of the pope?),” Razon recalled.

“On top of the bed was a laptop. I told another officer to take the laptop and run back to his office to check it. I did not want him to open it there,” he said.

What the police initially saw was enough to figure out the terrorists’ plan. The raid, after all, was a confirmation of an intelligence report gathered by agencies in the last quarter of 1994 that Middle Eastern terrorists were coming to the Philippines to assassinate the Pope.

“My theory was someone will wear the cassock and pretend to be a priest to get near Luneta or Pasay [where the Pope was scheduled to hold masses] and then plant the bomb. Or they will put the bomb in a car along the route,” he said.

Unknown to Razon at the time was that one of the two men who stayed at Doña Josefa was Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the first World Trade Center bombing in the US in 1993. Signs of Yousef’s presence in the Philippines were the first public evidence that Al Qaeda’s tentacles had reached Southeast Asia.

Yousef was able to evade arrest but his trainee, Abdul Hakim Murad, returned to the apartment and was caught.

“We only captured Murad, not Yousef. Plus, we got reports then that there was a training in Batangas. So I thought there must still be a cell out there that we have not accounted for,” said Razon.

Thus, Philippine security officials had to change the Pope’s routes.

He laughed during the interview as he recalled how even President Fidel Ramos, a graduate of West Point and former chief of the Armed Forces chief, found himself acting like the Pope’s security officer in the middle of the crowd at the Villamor airport.

The people at the airport and the crowd that later flocked to the Pope’s masses around Metro Manila did not know about the threat. The government was tightlipped about it and revealed it only after the Pope’s visit.

“Ang pinaka-ano (dasal) ko is sana huwag mangyari yung kinakatakot namin (My prayer then was that our worst fears will not be realized). Not on my watch,” said Razon.

Miracle: Smoke

The discovery of the Doña Josefa apartment was a “miracle,” said Razon.

Smoke, likely from the liquid bombs Yousef and Murad were preparing, triggered a fire alarm that sent the Manila Bureau of Fire Protection and accompanying cops to the apartment.

It was an opportunity the police almost lost. When firemen and cops responded, they saw nothing that raised an alert. There was no fire – only smoke. It was a false alarm, they thought.

But the inspector on duty at the nearest police station, Aida Fariscal, proved to be one inquisitive officer. When the cops mentioned to her that the room was rented by Arabs, the lookout bulletin that the PSG previously disseminated based on the 1994 intelligence report on “Middle Easterners” came to mind.

She and the cops rushed back to the apartment and caught Murad.

“If it wasn’t for her, we would not have known about the specific threat. I don’t think she got the credit she deserved,” said Razon. The PSG rushed to the apartment as soon as Fariscal reported it to them.

Philippine security officials reported the arrest to their counterparts in the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and only then realized the kind of terrorists they were dealing with. A few days later, an FBI team from New York arrived in the Philippines.

“When they arrived, the message of the Americans was: ‘Hey guys, you stumbled upon a gold mine,’” recalled Razon.

Blueprint for 9/11 attacks

Razon believes that Murad returned to the apartment for the laptop, which by then was already in police custody.

The files in it indicated that it wasn’t only the Pope’s assassination that the Philippines had foiled, but also Yousef’s plot to simultaneously explode 11 airlines for his “48 hours of terror” a few weeks after the Pope’s visit. The decoded files showed that the elaborate plot was called Oplan Bojinka, and Yousef had by then just finished testing his liquid bombs in the Philippines to make sure they could not be detected by airports’ X-ray machines.

The blueprint for the second World Trade Center bombing that happened 6 years later was also in the laptop – hijack a commercial airline and crash it into, among several targets, the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and the World Trade Center in New York. It was the brainchild of Yousef’s uncle, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed.

To make better sense of the files and get more information before the Pope’s arrival, investigators had to interrogate Murad. But it wasn’t easy, said a former police intelligence officer, one of the grizzled veterans who interrogated him. Murad – “a hostile captive” – was nothing like the criminals or tough communists that the cops were used to dealing with.

The officer said that even one general joined the interrogation of Murad, hoping to break the prisoner’s resolve. Out of frustration, the general ended up kicking Murad, the officer said.

But the interrogators were determined to get information from him before the Pope arrived in the country.

The book Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao, written in 1999 by Rappler managing editor Glenda Gloria and editor-at-large Marites Vitug, says Murad was tortured during interrogation. The chapter on terrorism also talks about how Yousef was forced to execute the plot in Manila when the local groups he was working with proved ill-trained for his sophisticated plans.

Murad was later extradited to the US while Yousef was eventually arrested in Pakistan. Philippine policemen testified during their trials. The two were both convicted in the US.

Seeds of Terror by Rappler executive editor Maria Ressa, published in 2003, details how Manila played a role in Al Qaeda’s plans in Southeast Asia and how it adjusted its strategy after the arrest of Yousef.

New challenges

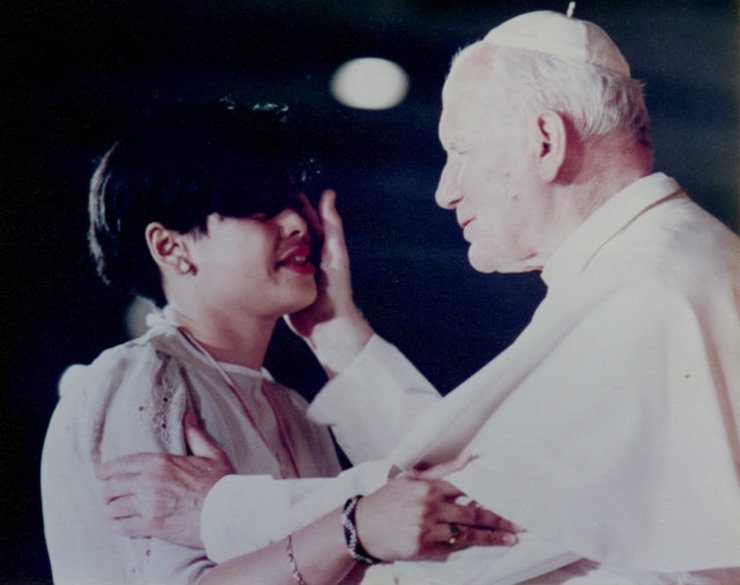

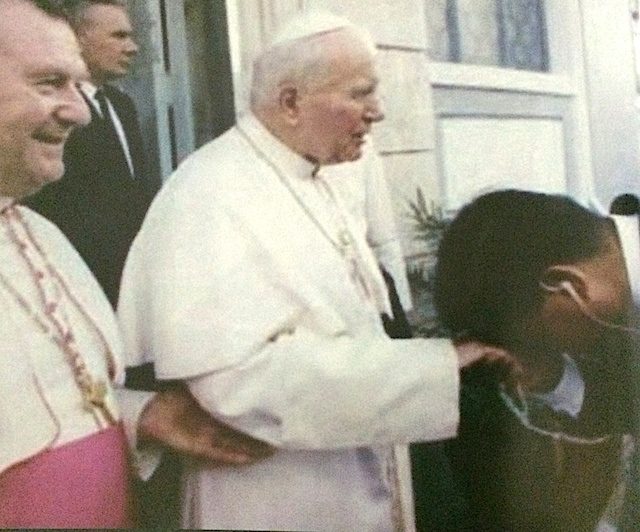

Looking back, Razon said the terror plot against John Paul II, now a saint, was one of the most memorable operations in his career after the years he spent fighting mutineers during the tumultuous term of Corazon Aquino. A photo of him kissing the Pope’s ring hangs on a wall at his residence.

“Noong nag-take off ‘yung Alitalia paalis ng pope, para akong nabunutan ng tinik (When his plane took off, I felt a huge load off my shoulders). Thank you, Lord,” recalled Razon.

But the fight against terrorism was only beginning.

Al Qaeda learned lessons from that episode, writes Ressa, scoring how governments failed to appreciate what was discovered in the Philippines in 1995 and allowed the terrorists to execute the 9/11 attacks.

Twenty-years later, the world now deals with a new terror group. The Islamic State (ISIS) represents the changing strategy of terrorists and the growing challenges that security officials face not only in protecting Pope Francis in his visit this week but in fighting terrorism in general, said the former police intelligence officer.

The military claims there is no serious threat against Pope Francis. It is true, said the former intelligence officer who maintains his own network of informants. “Wala akong nahahagip (We’re not catching any concrete information),” he said.

But he’s thinking of worst-case scenarios, like other officers we have interviewed. They have been wargaming for months, anticipating what possible threats Pope Francis may be exposed to.

“If I don’t do worst-case scenarios, that means I am not doing my job,” he said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.