SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It was a scenario that they had prepared for a hundred times over but in the end, could not prevent.

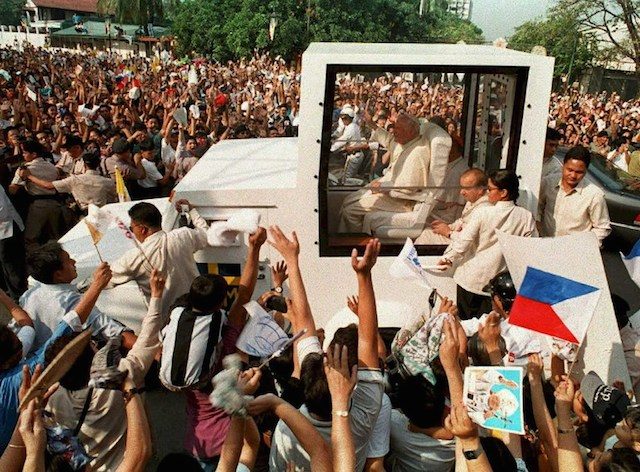

Pope John Paul II’s ceremonial procession during his second visit to the Philippines in 1995 started out routinely enough. But when the vehicle entered Roxas Boulevard, where thousands of Filipinos had been waiting for hours, it was nothing short of pandemonium.

The crowd breached security barriers, rushing towards the popemobile to catch a glimpse of the charismatic leader of the Roman Catholic Church.

“Wala nang magawa ang mga pulis (The police can’t do anything about it),” said a Filipino broadcaster in a clip from a 1995 news report. The trip that was only supposed to take 45 minutes in 1995 – from the airport to the Pope’s official residence, the Apostolic Nunciature – took hours.

It’s a scenario government officials want to avoid when the current Bishop of Rome, Pope Francis, visits the Philippines from January 15-19, 2015.

Government officials now estimate the same route will take 3 to 4 hours to travel, an adjustment from the 45-minute timeframe they originally set.

Things have changed since 1995, but in a way that could make securing the Pope an even tougher task – security threats in 1995 weren’t as pronounced, the Philippines had a much smaller population, and news took a little longer to reach people.

And as the Philippines prepares to welcome the so-called “People’s Pope,” his security team braces for the challenges of guarding a Pope known for his spontaneity, and making sure his legions of followers (including the onlookers) stay safe.

A papal visit in the predominantly Catholic Philippines, after all, is no ordinary visit.

“They have to consider…it’s like sending a saint [to the Philippines],” retired Philippine National Police (PNP) chief and former Presidential Security Group (PSG) deputy commander Avelino Razon Jr told Rappler.

When things don’t go to plan

Chief Superintendent Josephus Angan, then a Senior Inspector in the PSG, remembers John Paul II’s arrival as if it happened yesterday. Then commander of the PSG’s 1st company, Angan and his people were tasked with providing close-in security for John Paul II.

Call it instinct or presence of mind, but the moment the crowd came running, Angan and his team jumped out of their vehicles to surround the popemobile.

The PSG patiently pushed away bystanders who went too near, while keeping one eye on the Pope. Razon, who was in the vehicle trailing the Pope, had no choice but to jump out of his vehicle as well.

The PSG and police had every reason to be extra worried. A few days before, local police and the PSG stumbled upon an apparent plot to assassinate John Paul II. They would find out months later that it was part of a bigger plot, Oplan Bojinka.

But the security worries of government authorities go beyond their principal (in this case, the Pope). In a briefing with media, Roxas who is also chairman of the National Police Commission, explained they want to ensure both the safety of the Pope and his “flock.”

Officials now admit the 1995 papal visit could have gone better. There are, of course, things that security officials can do nothing about. John Paul II, for instance, deviated from the plan right away.

Instead of immediately alighting the bullet-proof popemobile after landing on Philippine soil, the Pontiff decided he wanted to greet the crowd that had gathered to welcome him.

Not even President Fidel V. Ramos could stop the Pope – he even had to act as John Paul II’s “security” for a few seconds.

The impromptu airport meet-and-greet and the much-delayed arrival journey were mere hints of a bigger problem the papal security team in 1995 would eventually have to deal with.

- Metro Manila cheat sheet: Routes, rules for #PopeFrancisPH

- What you need to know: Pope Francis’ UST visit

- Pope Francis in Luneta: Things you should know

- Flight cancellations: Papal visit in PH, January 15-19, 2015

- Where to stay during Pope Francis’ Manila visit

- FYI: No camping out where Pope visits

- Palace: No backpacks at Pope’s Luneta Mass

- No firearms allowed where Pope Francis will visit

- 10 tips: Stay healthy, safe during Pope Francis events

- 11 tips: Help keep Pope Francis venues clean, orderly

Sectors, barriers

In a country with a penchant for “breaking” world records and being the best in anything, 1995 was a memorable year. That year, some 5 million Filipinos trooped to Luneta Park to attend a mass celebrated by John Paul II.

More are expected to flock to the open-space venue this year – at least 6 million, according to government estimates.

Luneta during the 1995 World Youth Day was literally a sea of people. There was hardly any room to move; a small commotion could have easily triggered a deadly stampede.

This time, government officials have applied a “physics-based” approach to calculating just how many should be allowed in the enclosed portion of the park.

Only 700,000 people will be allowed in the area immediately fronting the Quirino Grandstand, where the altar for the mass is installed.

In the Typhoon Yolanda-hit province of Leyte, where the Pope will spend around 8 hours, wooden barriers are already in place to secure his route and the venue for the mass.

To make sure stampedes and overcrowding are averted, the area will be divided into quadrants and sub-quadrants.

Once one quadrant is filled, venue marshals move on to fill a different quadrant. The irony of surrounding Francis – known for his ability to “break barriers” – with all sorts of safety barriers is not lost on many.

For every area, there will be 8 police personnel, up to 400 AFP reservists, at least 8 Health Department personnel, around 8 Philipppine Red Cross volunteers and two marshals.

But Luneta will only be opened to the public at 6 am Sunday, January 18, through a sole entrance along Maria Orosa street.

Officials hope keeping the density to 3 people to a square meter will make it possible for medical personnel to step in if needed and for the Pope – spiritual leader to millions – to interact with his flock.

This was, after all, something John Paul II wanted to do in 1995. But, Razon recalls, there simply was no space.

‘What happened?’

In the 1995 Luneta Mass, trouble began even before the Pope could leave the Apostolic Nunciature. In fact, it began in the wee hours of the morning, as pilgrims began to occupy the area fronting the Vatican embassy.

One of the PSG officers assigned to billet security recalled Swiss Guards showing concern over the growing number of people outside the Nunciature.

The PSG alerted the Manila Police District (MPD), who was tasked with securing the area and routes leading to and from the Apostolic Nunciature.

A police general who was with the PSG in 1995 remembers how unpopular he was with pilgrims then.

“Galit silang lahat sa akin, nakikipag-away minsan. Minsan, nagmamakaawa (The pilgrims were mad at me. Sometimes, they’d pick a fight. Or they’d beg),” said the officer, who added they once had to turn down a high-ranking city official because he was not authorized to meet the Pope.

As billet security, it was their job to screen the people who went inside and outside the Apostolic Nunciature. It was also their job to allow or turn down the faithful who wanted to serenade the Pope or stand vigil outside.

Occasionally, the former PSG officer told Rappler, the Pope would step out of the Nunciature balcony and wave to the crowd outside. It was in those moments they remembered that above all, the Pope needed to fulfil his pastoral role.

The real nightmare came in the hours before the scheduled Luneta mass. By daybreak, the crowd was simply too thick.

The PSG team stationed at the Pope’s residence conferred with his Swiss Guards, and concluded it was not safe to transport the Pope to Luneta through the planned route.

To make things worse, the crowd in Luneta was already blocking the route the Pope was supposed to take. Another former PSG officer, assigned to check the safety of the Pope’s areas of engagement, still remembers how his immediate superior reacted to the news that the Pope could not leave the Apostolic Nunciature.

“Goddammit. Why did you let it reach that point? What happened?” his commanding officer berated him on the phone.

And so Plan B kicked in: they would exit a different (and less secure) route, and drive to the PSG headquarters in Malacañang where a chopper would airlift the Pope to Luneta.

But there was a problem: John Paul II was supposedly terrified of helicopter rides. The PSG officer said he was bawled out by his boss again because of that oversight.

In another 1995 event in the University of Santo Tomas (UST), the PSG had to push back the crowd because they were worried the stage would give in.

Such stories – of emergency airlifts, overcrowded streets, and pushy crowds – are why officials this time are not sparing personnel or resources.

For this year’s papal visit, some 25,000 cops have been deployed to secure routes and venues in Metro Manila and the province of Leyte. Another 12,000 Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) personnel will support the PNP, with more personnel from the Health Department, the Bureau of Fire Protection, and other agencies.

Officials are not discounting the same kind of emergencies during Francis’ visit. Should there be a stampede, a chopper will be ready to airlift the pontiff away from the crowd.

All in all, some 40,000 people are being deployed in Metro Manila and Leyte to secure the people.

Listen, please

It’s hard when your principal has his own plans and downright impossible when the crowd, or at least members of the crowd, have their own radically different plans.

Former PSG members remember with a snicker the hard-headed socialites in Luneta who demanded they welcome John Paul II upon his arrival via chopper. The helicopter John Paul II used had a strong down draft and there was an abandoned fountain nearby.

The strong wind and stagnant water were a predictably bad combination.

“I told them, ‘Ma’am, you better leave the area because the chopper is coming. You’ll get wet,’” he recalled telling a group of ladies.

They refused to budge. And true enough, the moment John Paul II’s helicopter began its descent, the socialites got drenched in cold, stagnant water.

PSG members themselves were nearly put in danger, no thanks to the over-eager crowd. The billet team’s quarters, an elevated container van, was in danger of falling when a rowdy crowd tried to get closer to the Apostolic Nunciature.

“The next day, we had the support for the container van reinforced,” one of the billet security team members said.

Razon recalls accidentally running over the foot of an old man who went too close to the papal convoy.

“But he wasn’t angry at us or anything. I guess he knew it was his fault – he shouldn’t have come too close,” said the retired police general.

Both the Palace and the papal security team have appealed to the public to follow the rules and safety procedures set by government.

“These are not inconveniences or if they really are, it is really for the greater good of the Pope and the public at large,” Interior Secretary Manuel Roxas II said in a previous statement.

In media briefings and internal meetings, the government’s papal security team always plays clips of the Roxas Boulevard stampede and shows images of the Luneta crowd in 1995.

It’s a constant reminder to current officials of the things that should not happen when Francis, the “People’s Pope,” visits the Philippines.

Security officials have also taken into consideration the fact that the popemobile is not bulletproof, as specifically requested by the Pope himself to represent the vulnerability of the Catholic Church and the Church’s relationship with the faithful.

Last-minute preparations and adjustments for this year’s papal visit seem to abound. President Benigno Aquino III, known to be a very finicky and hands-on boss, was reportedly unsatisfied with the papal security team’s report a little over the week before the Pope’s visit.

The President himself, in fact, conducted ocular inspections of the Pope’s official residence, the Quirino station of the LRT1, Luneta, and Villamor Air Base late Tuesday evening, January 13.

To some, the tens of thousands deployed and the undetermined amount spent for papal security is overkill. But for the uniformed men then – and now – who spent sleepless nights agonizing over each plan, a pope’s visit is incomparable to that of other dignitaries.

In separate interviews, both Razon and Angan recalled their amazement at the crowd that showed up to welcome and celebrate with the now Saint John Paul II.

The only event that comes closest? The People Power Revolution. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.