SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Lamont Strothers has not returned to the Philippines since 2002, his last playing year in the PBA. Now a high school coach, he vowed to stay put after an incredible basketball journey that took him to several countries.

“People laugh when I tell them this story. When I decided I was going to retire, I was going to let my passport run out. I was not going to renew it. That way, I wouldn’t have to get on a plane,” he shared.

But there’s one thing that might just lure the former San Miguel Beer stalwart back to the Philippines.

“I want to see the Tenement,” he said. “I saw it when they did a feature when Kobe (Bryant) passed. I was like, wow, that’s special.”

Strothers felt an affinity to the Tenement, a mass housing project in Taguig that’s home to a world-famous basketball court.

“I could identify with trying to play your way out,” shared Strothers. “That was us growing up. The systemic racism is real. Some of the kids in my neighborhood were projected never to be anybody. I was part of that African-American circle. You had to think your way out, meaning get high academic marks, or play your way out.”

Beating the odds has become standard fare for Strothers. That required envisaging plans and learning to reconstruct bigger dreams when circumstances forced him to change courses at midstream.

He first wanted to join the military, but an eye injury disqualified him from any branch of service. So he went to college and played basketball for the Christopher Newport University Captains, an NCAA Division III school.

Having an impaired vision was not an impediment to Strothers becoming a deadshot gunner who regularly lit up the scoreboard. He normed over 23 points a game in his collegiate career and was named All American and Player of the Year.

During the 1991 NBA Draft, he was selected in the second round by the Golden State Warriors, who traded him to the Portland Trail Blazers. As the 43rd overall pick, Strothers made history as the highest ever drafted Division III player.

Rude welcome

In his rookie year, Strothers made the NBA Finals against Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. He was part of a loaded Blazers backcourt that featured Clyde Drexler, Terry Porter, and Danny Ainge. A Blazer teammate was Ennis Whatley, who led San Miguel to the 1989 Grand Slam.

Strothers recalled his experience being in the grandest stage of basketball.

“I compare that to getting a doctorate in education. It was an eye-opener because it showed me how little I knew,” said Strothers.

“It gave me a blueprint on how to work to get better. You come in thinking you’re good and that you work hard. Then you realize the NBA is a totally different level. There’s a different way to train – in the weight room, on the floor, how you sleep, how you eat. It taught me how to be a pro.”

Strothers also shared how he got his life-long drive to excel.

“Watching my mother go through her journey, seeing different things in the neighborhood, trying to get my father’s attention because the spotlight was always on my brother, wanting to be like my brother who was really good were some of the things that fueled me,” he explained.

“You have to find something to motivate you. I tell everybody that you do not need other people’s permission to be successful. You take ownership of yourself and make that decision.”

Strothers played for the Dallas Mavericks in 1992-1993. He then saw action in the Continental Basketball Association (CBA) before taking his talents to Puerto Rico, Israel, France, and Turkey. In 1996, he found his way to the Philippines.

Locals have been known to give new imports a rude welcome by roughing them up. And Strothers recounted rather sheepishly the altercation he had with Jack Tanuan during a pre-tournament game before the Governor’s Cup.

“That didn’t go over too well,” he said. “It wasn’t really Jack Tanuan, God bless his soul. He just got the tailend of it. It was someone whose name I can’t seem to recall right now. He punched me and ran away so I chased him.”

He tried his hardest to remember the player’s name but it escaped him.

“I’ll know his name when I hear it. It will come to me,” he said, sounding exasperated that he could not remember.

A few days later, Strothers did remember: “Mosqueda was his name.” He meant Cadel Mosqueda of Mobiline.

Special place

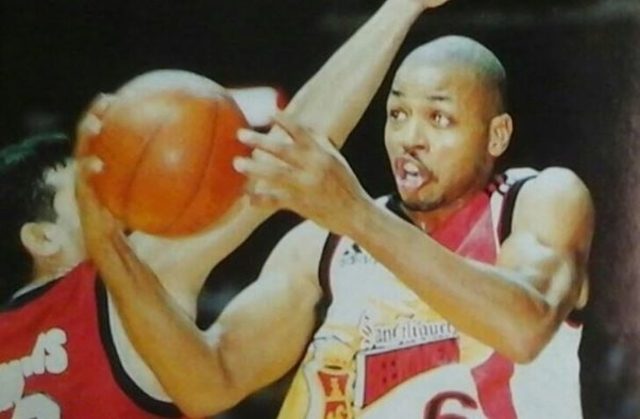

Strothers played 7 conferences in 6 years in the PBA as San Miguel’s resident import. He was named Best Import in the 1999 Governor’s Cup as San Miguel emerged champion. He came back the following year to defend and win the Governor’s Cup.

Now 52, Strothers had a chance to play for 3 different coaches during his years with San Miguel. He described the unique coaching styles he picked up from each one of them.

“Norman Black understood what I had to do to get the locals to buy into me. He helped me adjust and coached me to blend my talents with the locals,” he said.

“Ron Jacobs fine-tuned my ability to pay more attention to details. He taught me what to look for in tapes. He is the one who got me writing on the TV screen. He would pause the video and write on the screen. Now people see me do that here.”

“Jong Uichico was the peacemaker. He taught me how to stay calm,” Strothers shared. “I always played with a chip on my shoulder, the way my son plays now. I learned that the chip can remain there, but you don’t have to show it all the time.”

All these lessons he now applies as a high school coach and as a father. He also runs his own basketball camps and gets invited to different places to give motivational talks and share his basketball odyssey.

There will always be a chapter in Strothers’ story that will include the Philippines, which he says holds a special place in his heart.

“Outside of the coaches, the guys I got close to were Nelson Asaytono, Olsen Racela, Will Antonio, Allan Caidic, and Nic Belasco. When I was there, I had two drivers, Boy and Buck, whom I became very close to,” he shared.

“One thing I tell my people here is that Filipinos are very proud people, whether they have very little or they have a lot. It was basketball which brought me to the Philippines. It was the people who kept me there.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.