SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

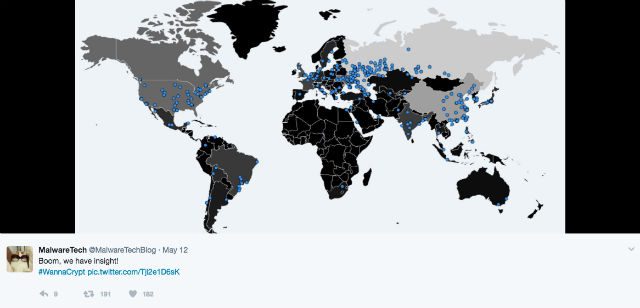

MANILA, Philippines – A massive cyberattack hit the world on Friday, May 12, United States time, affecting 200,000 computers in 150 countries – and counting.

The attack, making use of a malware called “WannaCry,” locked down the computers and encrypted the files within, rendering them unusable for the users. The actors behind the attack, which have yet to be identified, then asked the victims for ransom money to “free” the infected computers.

For this reason, the WannaCry saga is called a “ransomware” attack – one of the biggest ever. One chief research officer at a cybersecurity firm, Mikko Hyponnen of Helsinki-based F-Secure, called it the “biggest ransomware outbreak in history.”

As of writing, though, the infection and its effects have been somewhat contained, thanks to a United Kingdom cybersecurity researcher who goes by the handle @MalwareTechBlog on Twitter. The researcher, along with security firm Proofpoint’s Darien Huss, discovered the WannaCry “kill switch,” which has slowed down the malware’s progress.

The malware, however, continues to spread as new variants appear, stressing the need for the populace to remain vigilant and for the government, tech firms, and cybersecurity experts to sustain their efforts against the malware. (Read: Global pushback curbs cyberattacks but disruption goes on)

In the wake of the malware’s spread and current containment, what have we learned from these cyberattacks? Here are a number of lessons and observations:

1) The US government has been using software vulnerabilities as a tool.

The code used by WannaCry is said to have come from the United States’ National Security Agency. The NSA has been taking note of security vulnerabilities found in software used by people – in WannaCry’s case, Microsoft Windows – and been developing code to exploit these.

The code can then be used as a way to gather information from users, essentially like spyware. In WannaCry’s case, the code had been stolen and had fallen into the hands of criminal actors. In a blog post, Microsoft’s president and chief legal officer, Brad Smith, likened the leak to a missile being stolen from the US military: “An equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be the US military having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen.”

Smith also said that the governments of the world should treat the attack as a wake-up call: “They need to take a different approach and adhere in cyberspace to the same rules applied to weapons in the physical world. We need governments to consider the damage to civilians that comes from hoarding these vulnerabilities and the use of these exploits.”(Read: Microsoft says cyberattack should be wake up call for governments)

Rather than stockpile, sell, or exploit the vulnerabilities, Smith said, that governments should instead be required to report the vulnerabilities to software vendors.

2) Institutions, organizations have to be aware of their over-reliance on tech-enabled systems.

It’s unlikely and counter-intuitive for the world to go back to the old ways. But if there’s one thing that the attacks have re-emphasized, it’s that the world has evolved to be extremely reliant on computers, connected devices, and applications – perhaps a little too much so.

The question is, are we ready to completely rely on digital systems? The newest round of attacks appear to be saying otherwise.

The question rings even harder for certain sectors. Witness: Britain’s National Health Service (NHS). “Sixteen hospitals in the United Kingdom were forced to divert emergency patients after computer systems there were infected with Wanna,” reported cybersecurity blog Krebsonsecurity. This means that people could have died because the attacks put a stop to normal hospital procedures.

Given this and the current weaknesses of cybersecurity measures, should national healthcare systems rethink their reliance on computer systems, and come up with standardized emergency operational procedures that’s less computer-reliant? It’s a bandaid solution, but one that critical industries and sectors may have to consider – until cybersecurity measures prove they can prevent cyber strikes from grinding operations to a complete halt.

3) Cybersecurity needs a whole-of-society approach.

One reason that the attacks were so effective was that systems weren’t updated properly. Vendors, such as Microsoft, release security patches from time to time. For the vulnerability that the WannaCry malware exploited, Microsoft released one such patch last March 14, 2017.

However, not everyone downloaded and implemented the patch, contributing to the fast spread of the malware. What has happened highlights just how critical it is to keep systems updated. While a newer virus can just come in and override even the latest updates, implementing the latest available patches will still offer more security as opposed to not doing so.

Governments, as Microsoft suggested, need to understand that software vulnerabilities can be weaponized – and one that certain entities are looking to steal and use for criminal goals.

Microsoft and other tech companies, whose products are used by millions, will have to sustain efforts to enhance cybersecurity measures and cybersecurity awareness. Somehow, companies have to be responsible for their own legacy software too – especially when it’s still in use by a considerable number of people.

Microsoft, for instance, ended support and the issuance of security patches for their operating system (OS) Windows XP in 2014. Reports said that approximately 90% of healthcare facilities under UK’s National Health Service still use the 16-year-old Windows XP. The continuing use of the old OS is one of the conditions that contributed to the spread of WannaCry.

The question here is, how should tech companies deal with or help organizations that haven’t upgraded yet to newer systems such as Windows 8.1 or 10?

Should they push stronger for the adoption of the newer OSes and make users aware of the downsides of not doing so? Should tech companies be made to continue to support legacy software if it can be proven that people are still using them? Or should governments and its agencies, and private organizations be mandated to update their systems once support for a software officially ends?

We’ve already seen what happens when no action is taken.

4) Backing up one’s data can offer viable protection from ransomware

Ransomware finds leverage through the value of the information they kidnap. One simple way for people or organizations to make sure the malware can’t kidnap the information completely is to back up information or data on either the cloud or a separate storage. That’s one of the easiest way to prevent oneself from being victimized by ransomware.

However, it’s not a complete all-in-one solution. Sometimes, in the case of organizations or institutions employing individuals, the actual device is needed for operations. Organizations can indeed migrate their software-enabled operations to the cloud, but employees will still need an actual device to access the cloud. In this case, mere file backups will not suffice – unless the organizations are willing to invest in backup equipment to be deployed in emergencies. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.