SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), the government’s primary socioeconomic policy think tank, has released an extensive study on how the emergent technologies of today are changing the landscape of work due to their disruptive nature.

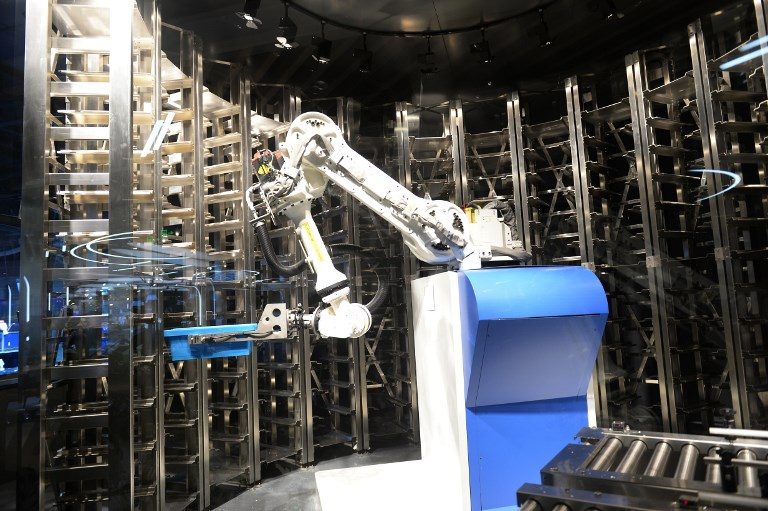

The study, called “Preparing the Philippines for the Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Scoping Study,” enumerates all these emergent technologies that embody the fourth industrial revolution – artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, data analytics, blockchain, cloud technology, to name some – and discusses what they are, their benefits to society, but also the potential disruptions they may cause.

Recalling the 3 other industrial revolutions of the past, the study puts the fourth industrial revolution in context: all revolutions are, by their nature, disruptive. They can bring about massive changes in society, among the most important of which is man’s value in industries where new technologies can seemingly do a more efficient job.

In the first industrial revolution, the value of man’s labor came into question as steam power began to drive industries. Today, in the face of smart technologies wherein more advanced, smarter machines can do more complicated, human-like tasks, man’s value in the workforce comes into question once again.

PIDS’ study is meant to probe this situation, showing how these technologies are being used now, how the Philippines can adjust to these disruptions, and what government policies can be established to foster a healthy, progressive relationship between the people and the new technologies.

The entire 110-page report can be found here.

For an overview, below we have prepared a list of key takeaways from the study.

Routine or codifiable jobs are most at risk

The study indicates two kinds of jobs: routine or codifiable and non-routine and non-codifiable. Computers and robots including those with AI capabilities are expected to replace routine jobs and complement non-routine ones. Examples of routine workers include assembly line worker, sewing machine operator, accountant, bank teller, and medical transcriptionist, to name some. Non-routine workers include managers, researchers, chefs, and those who are involved in unpredictable physical work.

What is non-codifiable now may be codifiable in the future

The definitions of codifiable and non-codifiable work are dynamic. As technology advances, so do the capabilities of robots and computers. Complex tasks that only humans can handle now may, in the future, be taken on by more advanced robots.

Currently, there is no definite time to when robots will start to replace humans in the threatened routine segment now. Some believe that technological availability and feasibility do not always mean outright adoption while some believe that when mass adoption comes, markets won’t be able to adjust fast enough without massive displacements. (READ: The Google tech that may threaten call center jobs)

Creative and social skills, a priority

The study mentions research by the US Department of Labor, which found that for workers to survive – both in routine and non-routine jobs – creative and social skills need to be acquired. These are two innately human skill categories that currently cannot be approximated by current robotic systems.

Judgment skills, problem-solving ability, intuition, and persuasion skills also hold high value in the face of automation.

2.2 million shop and sales persons and demonstrators at risk in the Philippines

Overall, a 2015 study by the International Labor Office estimates that 56% of all employment in Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are at risk of displacement because of automation. Industries in the following countries that are most at risk are hotels, restaurants, wholesale and retail trade, construction and manufacturing.

Those with low automation risk are education and training and human health and social work.

Millions of Indonesian office clerks, and hundreds of thousands of sewing machine operators and food service counter attendants in Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand encounter a high level of automation risk too.

Of these, women, lower-wage and less educated workers face a higher automation risk.

However, rather than outright displace workers, technologies can provide a boost in a complementary relationship

The study mentions a Journal of Economic Perspectives essay that says a mutual relationship with technology can be attained with proper human capital investment.

“Although computers substitute for workers in performing routine, codifiable tasks, they also amplify the comparative advantage of workers in supplying problem-solving skills, adaptability, and creativity,” the study says.

But in order to do so, “human capital investment must be at the heart of any long-term strategy for producing skills that are complemented by rather than substituted for by technological change.”

The education system must be adaptable, creative and flexible as well

To foster human capital effectively amid the constant threat of more and more jobs being automated, the study says that the education system must be flexible and modular. This is key to ensure that the system will be able to cater to quickly changing needs and diverse passions and interests of the students.

The study compares the ideal education system to that of LEGO blocks – modular, in the sense that it can mixed and matched with the “changing needs and interests of the students who will be facing a constantly changing work environment.”

It’s a time of rapid change driven by technology, and with a flexible education system, students will be trained how they can adapt quickly, and “work alongside machines rather than compete with them.”

The study also encourages “continuous improvement in the learning environment,” as it says that the “only way to keep up is to continuously learn, unlearn, and re-learn.” Illiteracy in the the 21st century is no longer defined as those who can’t read and write but those cannot learn, unlearn and relearn, it says, adding that lifelong learning, continuous training and retraining is now what’s asked of workers.

Robots continue to improve, and workers need to adapt to this, and constantly find their place through learning and relearning.

The Philippine picture

The World Economic Forum in their 2018 Readiness for the Future of Production Report defined the Philippines as the archetype “legacy country,” meaning the country has a strong production base (skills and manpower) but is weak in terms of maximizing this potential.

This is because the country has “weaker performance across drivers of production” including technology and innovation, human capital, global trade and investment, institutional framework, sustainable resources, and the demand environment. The report recommends significant investment in these areas in order for the Philippines to be ready for the fourth industrial revolution.

Currently, the Philippines is facing challenges in science, technology and innovation as it ranks 73rd out of 127 economies in the 2017 Global Innovation Index by Cornell University, Institut Européen d’Administration des Affaires (INSEAD), and World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). The country is behind Singapore (7th), Malaysia (37th), Vietnam (47th) and Thailand (51st) but ahead of Indonesia (87th) and Cambodia (101st). (READ: DICT: 48% of employees to be affected by automation)

Helping address the low ranking is DOST”s Science for Change Program (S4CP) which focuses on heavily investing in science and technology education, training and services. The program is also crucial to pushing for higher R&D spending from the government, with DOST pushing for a doubling of the budget yearly over the next five years to reach P672 billion by 2022.

The program, which proposes increasing scholarship slots, will be instrumental in increasing the number of research scientists and engineers in the country, which at 270 is below the UNESCO benchmark of 380, and far from Singapore (6,618), Malaysia (2,826), and Thailand (974). By 2025, the DOST expects to reach UNESCO’s benchmark.

Along with this, the DOST and the DICT also have other initiatives including the Balik Scientist Program, the National Broadband Plan, the National Cybersecurity Plan, and Tech4Ed as part of the government’s push for digital transformation. These initiatives can work hand in hand to make the Philippines more technologically adept, facilitate the adoption and absorption of newer technologies, and make Filipinos better-equipped at striking a complementary working relationship with these.

The Philippines is far from the technological and knowledge frontier, and cannot be, at this point, categorized as ready for the fourth industrial revolution. To become ready, however, the study makes a recommendation. (READ: New skills needed as automation shifts job landscape – World Economic Forum)

Urging to build slowly but steadily, the study warns that it’s “risky to rely on hubristic leapfrog strategies, but must instead “focus on establishing a solid basic foundation for sustained learning and on accumulating various types of capital, while progressively and systematically closing the existing technological and knowledge gaps.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.