SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

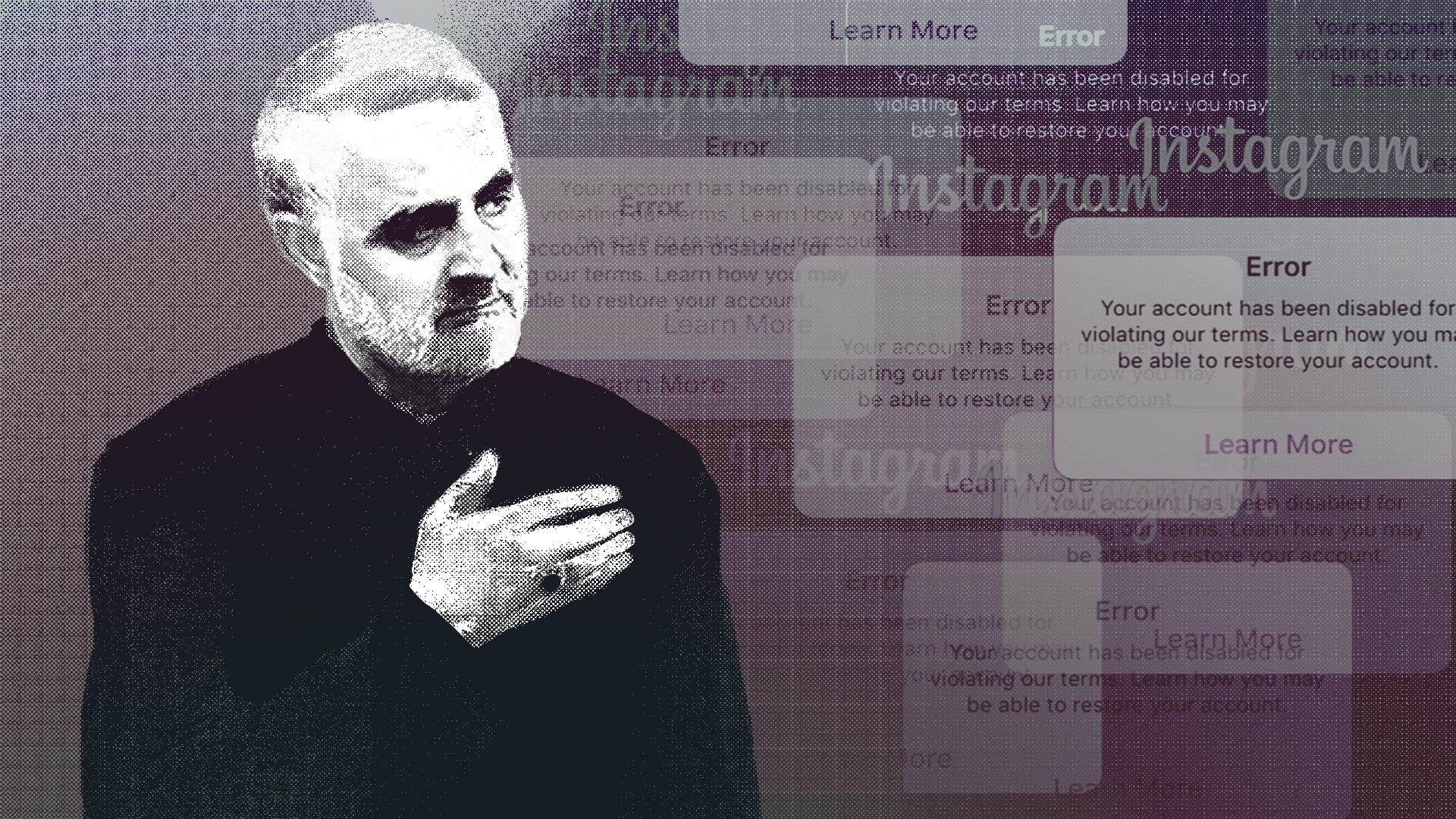

After a U.S. drone strike killed Iran’s General Qassem Soleimani, Iranians flocked to one of their favorite platforms, Instagram. But in the days following the general’s death, journalists, activists and ordinary Iranians have experienced shutdowns and censorship – not from Iran, but from Instagram.

At least fifteen Iranian journalists have reported having their accounts suspended, according to the International Federation of Journalists. Government-owned and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-affiliated media agencies such as Tasnim News Agency, the Iran Newspaper and Jamaran News all had their accounts, with a combined hundreds of thousands of followers, removed entirely by Instagram. “This poses an immediate threat to freedom of information in Iran,” the International Federation of Journalists said in a statement.

Iranian influencers, human rights advocates, and activists are also experiencing account shutdowns.

“It’s very widespread, it’s huge,” said Amir Rashidi, an Iran internet security and digital rights researcher based in New York, who watched on Instagram as account after account in Iran was shut down or had posts removed after users discussed the killing. “Every person I saw that posted about Soleimani on Instagram, almost all of their posts have been removed.”

IRGC affiliated Tasnim News Agency (@Tasnimnews_Fa) has its Instagram profile removed following Soleimani’s assassination. Unclear if because of Soleimani’s terrorist designation and their coverage of him. Semi-official @FarsNews_Agency remains live, with commemorative posts. pic.twitter.com/nboZk1bLTu

While Facebook, Twitter and Telegram are all blocked by the government and can only be accessed through a virtual private network, Instagram is one of the few Western-built social media apps not yet banned by the government. The platform has an estimated 24 million active users in Iran and is an important communications tool – though reports say it’s about to be blocked by the government, too.

“The only platform where we could freely express ourselves was Instagram,” said Rashidi. “And now Instagram is censoring us.”

Instagram said that in removing posts in praise of Soleimani, it was complying with U.S. sanctions law. In April 2019, President Trump designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a foreign terrorist organization. Shortly after Trump’s designation was announced, Instagram removed a number of Revolutionary Guards’ pages, including that of Soleimani himself and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s English-language page, which the company later reinstated.

Stephanie Otway, a Facebook company spokesperson, said: “We operate under U.S. sanctions laws, including those related to the U.S. government’s designation of the IRGC and its leadership.”

Instagram said any accounts maintained by or on behalf of the Revolutionary Guards, as well as content that supports it, are in violation of its community guidelines banning terrorist content.

“This is just a field of law that really hasn’t been written quite yet,” explained Eliza Campbell, associate director at the Cyber Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C, who said the existing laws had failed to keep up with online speech. “The terrorist designation system is an important tool, but it’s also a blunt instrument,” she said. “I think we’re walking down a dangerous path when we afford these platforms – which are private entities, have no oversight, and are not elected bodies – to essentially dictate policy, which is what’s happening right now.”

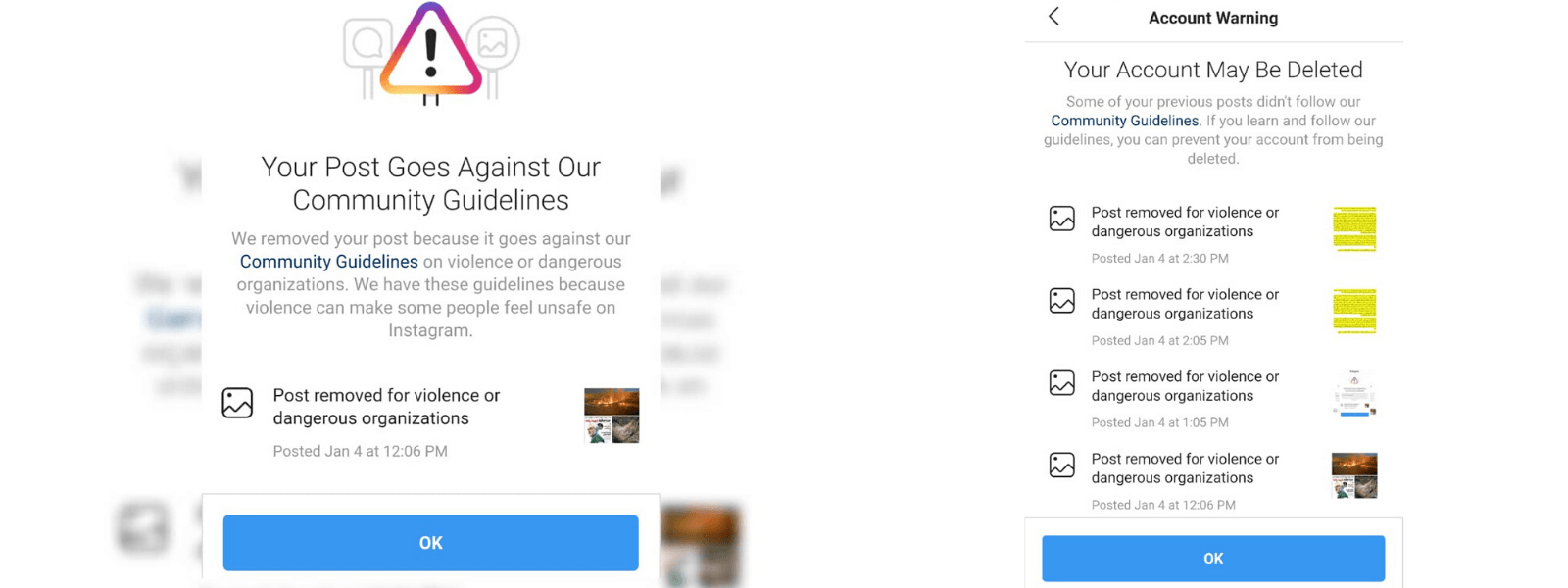

Prominent human rights advocate and investigative journalist Emadeddin Baghi, 57, who has nearly 40,000 Instagram followers, also had four of his Soleimani-related Instagram posts removed. Baghi, who has been imprisoned multiple times in Iran, is a well-known critic of the IRGC. “I shared a post that had two parts,” Baghi said. The general’s death, he wrote, had “saddened some, and made others happy,” but that the assassination “was an act which is contrary to the principles of international law.”

In the post, Baghi also reflected on how Iran reached this point in history, and how it could have been avoided. Baghi described the post as daring given the current emotional climate in Iran. “In fact,” he said, it was “a criticism of the government’s policies.” But Baghi is nonplussed as to why the post was deleted: “which of these words is really questionable on Instagram?” he said.

“If you learn and follow our guidelines, you can prevent your account from being deleted,” the Instagram app warned Baghi. He believes the reason for the post’s deletion may be as a result of describing the general’s death as a “martyrdom,” a view held by many Iranians, who see Soleimani as a uniting figure that fought Saddam Hussein and ISIS.

“When it comes to non-English languages, their tools and metric for designating dangerous speech are really sloppy—or at least, underdeveloped,” said Campbell. “My guess is they have a list of danger-words, and the word for “martyr” in this case was probably one of them.”

The Iranian diaspora has also been affected by Instagram’s crackdown. Norwegian-Iranian businesswoman Bahareh Letnes, the partner of Norway’s former fisheries minister, also had her posts removed. Letnes, 29, who has a following of more than 20,000 on Instagram, had posted a black-and-white photo of Soleimani, describing him as a “war hero” and adding: “I hope the US military is now thrown out of the Middle East forever. Rest in peace.” Her post was deleted by Instagram.

“I was not surprised, because I knew censorship and lack of freedom of speech exist all over the world,” Letnes said. “Instagram said I am not allowed to use violent images. Can you show me violence here?” she said, in reference to one of her posts depicting the general. “Instagram thinks the image of Soleimani is violent.”

“The United States must gladly suspend my account, censor me, threaten me, but I will not be silent,” Letnes wrote in another Instagram post on Tuesday.

On Monday, an Iran government spokesperson, Ali Rabiei, condemned Instagram for shutting down discussions of Soleimani. “In an undemocratic and unashamed action, Instagram has blocked an innocence nations’ voice protesting to the assesination of General #Soleimani,” he tweeted.

In November, the Iranian government shut down the internet for a week, denying millions access to the web. For years, Iran has been building a government-controlled “intranet”, and are also creating a domestic platform to replace Instagram as the government prepares to block the app. Iranians fear the November shutdown was a precursor to a permanent internet blackout.

Rashidi said Instagram’s removal of Soleimani-related content has played into the hands of Iran’s leaders and their campaign to build an internet that’s ring-fenced off from the world. “It’s a huge propaganda gift for the Iranian government—these companies need to understand the consequences of their decision,” he said. “They are basically helping the Iranian government control the Iranian people.”

Iranians are already attempting to get around the threat of deletions and account shutdowns. “People are self-censoring. When they post something about the situation they try not to mention Soleimani’s name or the IRGC,” said Rashidi. “It seems there is no platform ever for us to express ourselves or speak our mind.” – Rappler.com

Isobel Cockerell is a reporter and filmmaker with Coda Story. A graduate of Columbia Journalism School, she has also reported for WIRED, USA Today, Rappler, The Daily Beast, the Huffington Post and others.

This article has been republished from Coda Story with permission.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.