SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When Arief’s cell phone service was cut off, it came as no surprise. He had refused to visit the local branch of his mobile provider and give his fingerprints and a facial scan, in order to register his SIM card. He did so as a matter of principle, to show his opposition to what many believe to be increasing intrusions into the lives of Malay Muslims by the Thai authorities.

Arief, 21, is currently unemployed, and lives in Songkhla, one of Thailand’s Southern Border Provinces (SBPs). Unlike the rest of majority-Buddhist Thailand, this region is largely populated by ethnic Malay Muslims. It has also been under some form of military control since 2005.

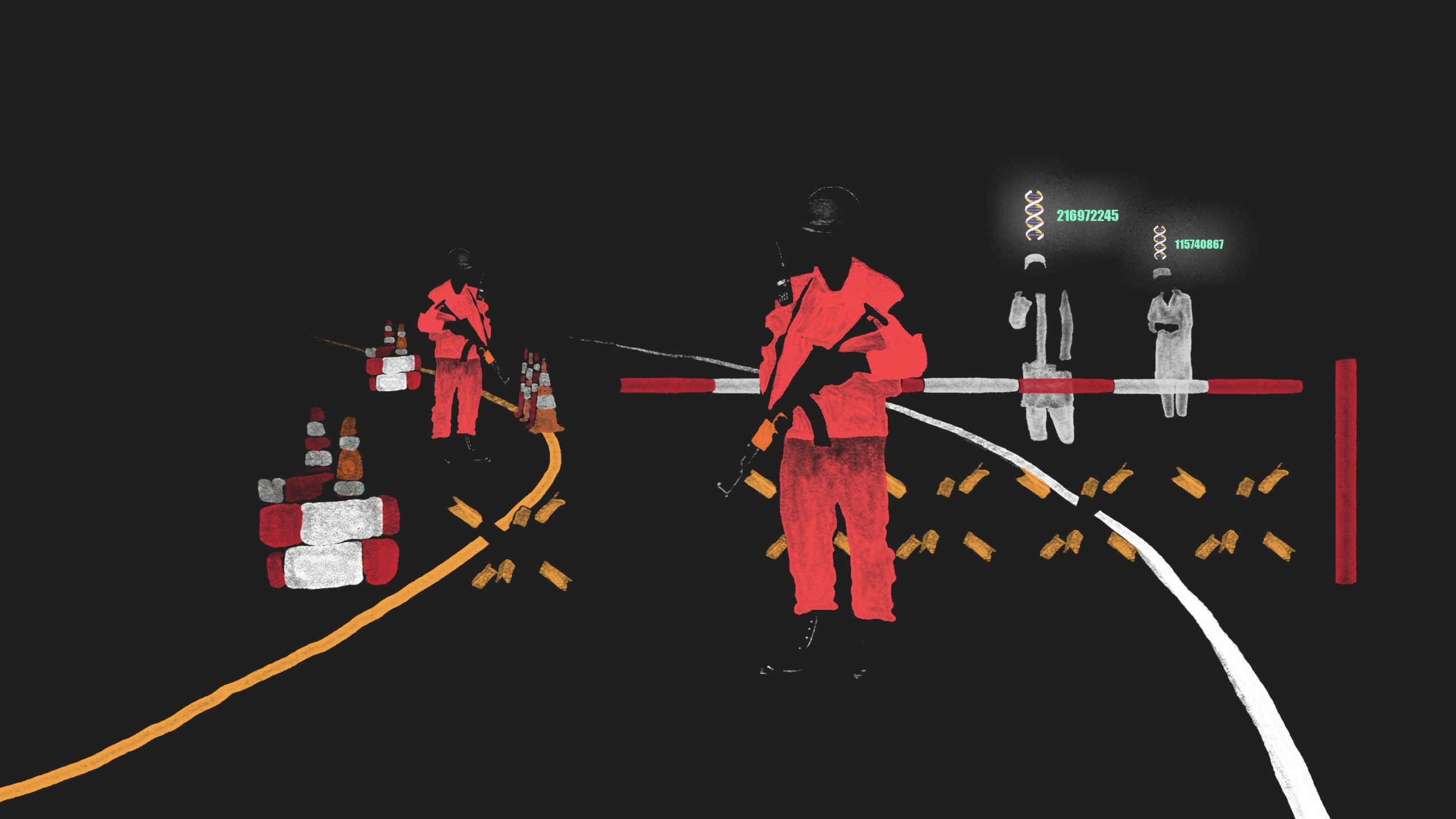

While Thais elsewhere have to register their SIM cards by showing a passport or government-issued ID, biometric registration has been mandatory for all residents of the SBPs since April. This move comes alongside a proliferation of surveillance technology that human rights groups believe could be used by Thai authorities to monitor minority groups.

The longtime imposition of military control by Bangkok, along with excess use of force by authorities has left many Malay Muslims distrustful of the state and concerned about how these technologies will impact their lives. While many of Arief’s friends and family have chosen to sacrifice privacy for convenience, he remains resolute.

“I don’t trust the government,” he told me, via Signal, using his home internet connection. “They will take advantage of this to further suppress our voices.”

Authorities argue that such measures are necessary to counter violence in the region. Since 2005, an armed insurgency, led by pro-independence groups such as the Barisan Revolusi Nasional (National Revolutionary Front), has carried out attacks targeting Thai civilians. At the same time, Human Rights Watch has documented abuses against Malay Muslims by Thai Security forces, including “extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture of suspected insurgents.” All in all, more than 7,000 people have died as a result of state or separatist violence.

“The conflict has left us with a region which is administered and governed, when it comes to conflict, territory, people and budgets, in ways that are visibly differently from other parts of the country,” said Romadon Panjor, editor of Deep South Watch, an organization that collects and analyzes data on conflict in the SBPs.

According to Chanatip Tatiyakaroonwong, a researcher, who has done extensive field work on biometric technology and data collection in the SBPs the increased militarization of the SBPs since 2005 has resulted in discrimination against Malay Muslims. He believes current and future uses of technology will only reflect this power imbalance.

“In everyday interactions, Malay Muslims are subject to racial profiling at checkpoints,” said Tatiyakaroonwong. “This is the same kind of racial profiling, but through an automated channel.”

Surveillance and monitoring technology is being used more and more by Thai security forces in the SBPs. For instance, here have also been media reports that ethnic Malay Thai citizens crossing the border from Malaysia have been subject to forced DNA collection, with some under the impression it was for Covid-19 testing.

According to Pornpen Khongkachonkiet, director of Thai human rights organization The Cross Cultural Foundation, “DNA collection was, before, very selective, for suspects, prisoners, or detainees, but now, they have been using this forced DNA collection for the greater population.”

Her organization has documented more than 100 cases of forced or involuntary DNA collection of Malay Muslims by security forces in the SBPs during anti-insurgency campaigns. They believe this is just a small fraction of the actual total.

Khongkachonkiet does not believe it is a coincidence that the SBPs form the first region in Thailand to see the installation of a widespread, AI-enabled CCTV surveillance system. In all, 8,200 cameras have already been installed in the SBPs, supervised by the National Security Council in Bangkok.

The government is framing this expansion of surveillance technology in a beneficial light.

“The biometric technology promises more accuracy in determining who is an insurgent,” said Tatiyakaroonwong. “It sets an expectation for law enforcement and the military that they are finally going to find all the insurgents, put them in jail and restore peace in the region.”

However, many people have concerns relating to both data privacy and oversight of security forces operating in the region.

From 2014 to 2019, Thailand was under the control of an unelected military junta. Before ceding some power to Parliament in elections last July, the junta enacted a number of laws that increased state control of digital technologies and data. They still retain total control over the upper house of Parliament, of which all 250 members are appointed by the military, and there’s been no change to their special role in the SBPs.

Its amendment of the Computer Crime Act in 2016 gave the government “nearly unfettered authority to restrict free speech, engage in surveillance” and “conduct warrantless searches of personal data, according to Article19, a United Kingdom based NGO which focuses on freedom of expression. The even more controversial 2019 Cybersecurity Law gave the state power to search and seize data and equipment in cases deemed matters of national security, all without court orders.

“We don’t have the robust personal data regulation, and when it comes to the Cybersecurity Law, the authorities can access information gathered by internet service providers,” said Sutawan Chanprasert, coordinator of internet research at the Bangkok NGO Digital Reach. “There’s no guarantee against misuse after the data is gathered, and no law that stipulates what state agencies can do with the data.”

Last year, Thailand passed a bill that would create a national digital ID system. Now, human rights groups are concerned that this scheme could be integrated with the country’s growing biometric infrastructure.

“If they merge the biometric technology with the digital ID, it could be disastrous because of the lack of protections in the law,” said Chanprasert. “If a lot of information is going to be integrated, it might allow the government to track citizens.”

There is also little to no transparency about who is providing the surveillance technology being deployed in Thailand. Military spending is highly opaque, and organizations like CrCF have been unable to ascertain which companies or countries are behind the systems.

“We don’t really have any level of access to that information,” said Khongkachonkiet.

What is known is that Mengvii — a Chinese company that designs image recognition and deep learning software and is currently blacklisted by the U.S. government for being implicated in human rights violations in Xinjiang — has been focusing its attention on Thailand. It’s Face++ facial recognition technology was demonstrated to Thai government officials and police departments in 2018.

For now, though, opposition to the use of biometric technology in the SBPs is strong. In addition to those residents who, like Arief, are refusing to register their biometric data for a SIM card, others are refusing to provide DNA samples to security forces. A growing debate about whether or not to provide biometric data to the authorities is also playing out on Facebook.

“People are becoming more and more vocal about the possibility of misuse on these technologies,” said Tatiyakaroonwong.

Many Malay Muslims are also aware of how surveillance technology has been used to repress other minority populations around the world, including the Uyghur community in China.

However, events in the SBPs tend to attract little attention in the rest of Thailand and concerns about the rights of Malay Muslims generally come a distant second to matters of national security.

“Biometrics and other technologies seem to be far away from the general public in the rest of Thailand,” said Khongkachonkiet. “But as surveillance technology creeps into the daily lives of Malay Muslims in the SBPs, with time, it may someday creep into the lives of all Thais.” – Rappler.com

Illustrations by Gogi Kamushadze

Nithin Coca is a freelance journalist who covers the social implications of technology in emerging economies and developing countries. His work has appeared in Al Jazeera, Quartz, Foreign Policy, Vice and a number of other publications.

This article has been republished from Coda Story with permission.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.