SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – For every major film festival, film-centric sites would have a list of cameras used by every participant, containing familiar names such as Arri, Sony, Panasonic, Red and the now common Blackmagic – but seldom would a smartphone brand be included.

Tangerine is a full-length film by Sean Baker that was a hit in the Sundance Film Festival last January. It involves two transgender prostitutes – Sin-Dee Rella and Alexandra, as they search the streets of LA for Chester, Sin-Dee’s cheating boyfriend/pimp.

More than the colorful plot, what generated interest for the film was when the credits rolled and it was revealed that the film was all shot using an iPhone 5s, 3 of them – and it looked good.

Sure, there were add-ons for the device – a $160 Anamorphic Adapter from Moondog Labs and the award-winning $8 FiLMiC Pro app for the iPhone, but it remains that at the core, it was the smartphone that put it all out.

Before it, there were already numerous short films in the internet that was shot via smartphone, most popular was Park Chan-wook’s Paranmanjang (Night Fishing) in 2011 – a 30-minute short which won the Golden Bear for Best Short Film at the 61st Berlin International Film Festival.

Smartphones have been certified

With Tangerine picked up by Magnolia Pictures for a limited US release in July, smartphones had been legitimized as a tool for filmmaking – not just an accessory as a light meter or preview monitor, but as a full-fledged camera for a feature film; and manufacturers are responding accordingly.

In 2013, Nokia announced the Lumia 1020 with a 41mp camera. Then Panasonic went back to the smartphone game at September of last year with a camera-focused model, the Lumix CM1, touting a lens made by Leica.

On the more popular end, Samsung and Apple have both steadily improved their cameras with every release. Add to that the tons of apps and accessories being made available to make shooting with your smartphone more friendly and you have a great ecosystem for the platform.

It all seems good, but one thing no one expected was how fast smartphones would eat up the market of digital cameras.

Quick reigns

It wasn’t long ago when digital SLRs took over film when the Canon 300D was made available with a sub-$1000 tag. Nikon went lower in 2006 with their Nikon D40, priced at $499. Canon then seemed to win it all in 2008 with their 5D Mark II – the first DSLR to have Full HD video recording capability – which became a standard for most videographers all over the world.

At the time when professional cameras were expensive and bulky; and camcorders lack the depth of field of professional cameras, DSLRs stood as a viable alternative in professional video production.

Fast forward to 2015 and both companies are in trouble. According to Reuters, Canon’s net profit fell 28.7%, raking in 33.93 billion yen ($285.27 million), compared to the 82.6 billion yen from the same quarter last year – thanks to strong sales of office equipment while their imaging department suffered a 22% decline.

After a 9% decline in sales for 2014, Nikon further skidded down, posting a 15% and 12% decline in sales and income respectively for their first quarter of the year, citing the ‘delayed market recovery in China and Europe’ as main reason. They know that it won’t be the end of the tunnel soon as in the same report, they stated that for the same quarter next year, they expect a decline of 10 percent in sales and 33 percent in income.

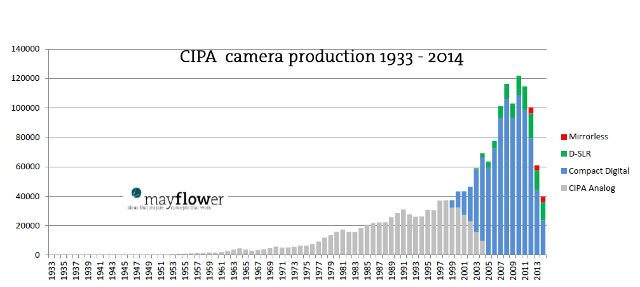

The Camera and Imaging Products Association’s (CIPA) 2014 report showed that shipments of cameras dropped 30.9% from the previous year, with compact cameras accounting for most of the losses.

The landscape changed when Instagram was announced on October of 2010, and caught fire the scene just a few years after. People were suddenly burdened of the workflow imposed by cameras, and they shifted to smartphones and tablets despite the photographic limitations.

Smartphone images are generally smaller, compared to the 2mb-4mb average of compacts. Speed was also a crucial factor because cameras require transferring of images from camera to computer before being uploaded, compared to a few clicks from the smartphone.

This, along with the buzz created by Tangerine, would further put the industry into a decline.

Fun! Fun! Fun!

Instagram gained popularity not only because of its streamlined sharing capability but because it’s just fun. They enabled easy-to-use filters, above all else, which made them appeal to users. On the other hand, brands kept marketing compact cameras as something that gives out a professional look, which doesn’t appear to matter anymore.

Proof that consumers are into ‘fun’ things? Fujifilm Instax. For a while, people bought it because of the distinct look of their images. It’s different, easy to use, looks good, but expensive. Its box of special paper containing about 10 sheets costs around P350 to P400 ($7-9), slowing its momentum considerably.

In Japan, there’s a thriving market for toy cameras – small, toy-looking plastic cameras that take captivating images. The most popular are the Digital Harinezumi – a lo-fi camera that simulates film outputs – and the new Rhianna.

With the Harinezumi in its fourth version after its 2009 debut, it has garnered a cult following, even used by Terrence Malick in the intro of his film ‘Into The Wonder’ and Filipina filmmaker Pam Miras used it for her full-feature, Pascalina – which was awarded Best Film at 2012 Cinema One Originals. The Harinezumi simulates vintage looks via filters, while the Rhianna does the same but with a more modern look.

By now you would ask “Is this a filter game?” Well, no. Aside from being novice friendly and having film-esque filters, these toy cameras are very small. The Harinezumi measures at a mere 9cm horizontal and 3.5cm vertical; while the Rhianna is a bit heftier at 10cm horizontal, 6.5cm vertical and features an extended lens.

If brands want to win back consumers into using their cameras, they would have to be smaller than a smartphone, and have to be fun for consumers. They have to stop marketing things as ‘pro-like’ and being all technical about their approach; most people do not really use those scene modes and do not care how high the ISO can be because of flash.

Show them images, show them how non-intrusive the camera can be if they bring one along on their trip, give them features that they would definitely use – like Harinezumi’s Double Exposure, and Rhianna’s square image option (useful because of Instagram’s square rule), give them something that would flawlessly work, that they could just click away at the shutter.

This is supported by market research from Mayflower Concepts. In their presentation at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) at Las Vegas last January, they contrasted the iPhone with a mirrorless camera, saying the operation of a high-tech product like an iPhone is subjected to swiping compared to the camera with four selection wheels, ten operational buttons, and not to mention the numerous things in the menu. They ended their presentation by saying that brands should “change [their] style of communication away from technology and towards ‘fun of photography.’”

Adapt or concede?

If developing a new camera category would be too risky, why don’t they just go Sony’s route? 40 percent of all camera sensors in 2014 were made by Sony, and it’s a good business.

Ars Technica said that it is giving the company good income, especially since it’s the one developing the sensors for the iPhone and the rising Chinese brand Xiaomi.

The business went from 320 million units to 450 million this year, or 16.5% more revenue and 36% higher operating profit. A Wall Street Journal report said every iPhone 6 sold generated up to $20 for the Japanese company.

For Canon and Nikon, both long time players in the industry, they could lend their expertise in lens making to smartphone brands and collaborate on products’ cameras, like what Leica did for the Panasonic Lumix CM1, a $999 underpowered smartphone that’s focused on imaging.

In a teardown report from IHS, the rear camera module of the Samsung Galaxy S6 Edge costs $18.50, while the front camera is at $3.00 for a total of $21.50. Take that into Samsung’s expectation of 70 million units sold by the end of the year – a figure highly possible as Forbes reports that the unit is selling out due to high demands and either Canon or Nikon will sit at an expected gross income of $1.5 billion if they were to make the sensor and lens for both cameras at the same price point.

It’s undeniable at this point that smartphones are dominating over the casual users and it’s paving its way into several art forms as well. Camera companies should really consider either making a ‘fun’ camera or lending a hand to smartphone companies instead of making competing ‘pro-like’ products and burning money by marketing them.

Besides, unlike the fall of film, the smartphone didn’t eat into the professional market. It’s logical to focus on semi professional cameras and higher.

During the 2014 Golden Globes, Netflix received more affirmation for its projects after House of Cards and Orange is the New Black were nominated, to which Amy Poehler said during the opening monologue, “Enjoy it while it lasts Netflix, because you’re not going to be feeling so smug in a couple of years when Snapchat is up here accepting Best Drama.”

With the right artist behind the lens, that might really happen. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.