SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Cloaked politics: The political involvement of non-political Facebook pages in the 2022 presidential elections](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/04/fb-pages-presidential-election-2022.jpg)

This is a study presented by the authors in the #FactsFirstPH research briefing held on April 8, 2022. The full copy of the research is reposted with permission.

Extant studies have documented and analyzed the use of Facebook pages during elections in the Philippines and abroad. Citing data from Facebook’s Ad Library, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism shows that candidates for the May 2022 Philippine general elections are spending on Facebook advertising. Scholars Christine Williams and Girish Gulati’s 2013 study characterized the use of Facebook for political campaigns during the 2006 and 2008 US polls. In a comparative analysis of 18 election campaigns, researcher Diego Ceccobelli examined in 2018 how political leaders in advanced industrial democracies maximize the platform to “personalize” their political communication.

This is consistent with scholar Jayson Troy Bajar’s findings that the most dominant themes found on the Facebook pages of presidential candidates during the 2016 Philippine general elections were political advertisements and self-descriptions.

But aside from posts from official campaign pages, election-related content circulating on Facebook is also generated by pages owned by supporters and news organizations reporting about politics. Non-partisan Facebook pages are also found to be active participants in political discourses during elections. In 2020, scholars Anastasia Goodwin and others documented how political organizations were employing the services of coordinated networks of social media influencers for political campaigns during the 2020 US polls. In the report released by University of Texas’ Center for Media Engagement, experts and political strategists admitted to the practice of leveraging the “authenticity” of nano-celebrities on social media who are capable of cascading political messages to hyper-specific audiences.

The ethics of using non-partisan Facebook pages for election campaigns, whether paid for or otherwise, remains to be subject of debate as some political strategists would claim that the practice is merely tantamount to “digital door-knocking” and is no different from how celebrities are canvassing for votes in favor of candidates they support. However, Goodwin and other researchers also observed that the “scale of reach, the influencers’ relationship with their audience, and disclosure and transparency” make such political strategy deceptive and akin to digital astroturfing—a coordinated inauthentic behavior of social media accounts that “creates the false impression that a campaign has developed organically.”

In the Philippines, obfuscated Facebook pages created by “second-level subcontractors” who are part of a hierarchy of networked “disinformation architects” favored President Rodrigo Duterte’s bid during the 2016 Philippine general elections. The study drew an important distinction between celebrities and pundits actively and openly influencing political opinions and anonymous micro-influencers involved in “more clandestine political operations.”

What is clear from these findings is the strategic use of Facebook pages in reaching audiences for political communication and how campaigning has expanded from traditional sources of political messages such as the media, to emerging political intermediaries, such as online nano-influencers. Our paper provides evidence that political campaigning in contemporary media does not just end with political influencers and nano-celebrities – actors have penetrated non-political spaces, and seemingly non-partisan pages, with their reach and ability to cascade political content to diverse audiences, are serving as venues for strategic political

communication.

At the same time, we also demonstrate how non-political pages are activated to be part of disinformation campaigns and validate the involvement of obfuscated non-political Facebook pages in online discourses surrounding the 2022 Philippine elections. We also argue how their seemingly neutral interface serves as conducive channels for coordinated sharing of election-related propaganda and disinformation reaching millions of otherwise disinterested and non-partisan audiences.

Methodology

Data collection

Our corpus was extracted from a dataset of 2,162,463 Facebook posts that contained election-related keywords, which included names of presidential and vice-presidential candidates, political parties, election hashtags, and other election words published from May 1, 2021 to January 31, 2022. The data was scraped using CrowdTangle, a social media listening tool developed by Meta, the technology conglomerate that serves as the parent organization of Facebook.

Corpus extraction went through multiple layers of filtering prior to analysis (see Table 1). First, we extracted posts published by Facebook pages with Philippine-based administrators. Second, since we are primarily interested in posts that came from pages traditionally conceived and appear as neutral about election matters, we used page categories as another filtering criteria. To reduce the number of pages that only incidentally mentioned the keywords that we used in the initial scraping, we selected posts from high-volume categories (i.e., categories that contained a lot of posts). We used a cut-off number of 194 posts, which was calculated as the minimum outlier1 value in the upper bound of our dataset.

From a set of 537 categories, we were then left with 96 categories, with posts ranging from 200 to 60,749. In the third layer of filtering, we manually labeled each category as either political or non-political. Political categories are those that are directly linked to electoral and political matters (e.g., POLITICIAN), including those that share election updates (e.g., MEDIA_NEWS_COMPANY), information about policy and governance (GOVERNMENT_ORGANIZATION), campaign-related materials (ADVERTISING_MARKETING), advocacy messages (NGO), and other related matters. This label also included categories of individual content creators or personalities (e.g., PERSON, BLOGGER, and ARTIST), who share content related to the elections in their pages. Meanwhile,

categories labeled as non-political are those known to contain pages about special interest topics (e.g., CLOTHING, TRAVEL_SITE, HEALTH_BEAUTY), entertainment (e.g., TOPIC_JUST_FOR_FUN, SONG), and other categories for niche audiences (e.g., COLLECTIBLES_STORE, SOCIAL_CLUB). Posts labeled under this set of categories were

included in the next stage of filtering.

Finally, to ensure that the corpus is made up of pages that appear to be non-political, we removed pages that contained election-related keywords in their page name and page description, or fields that are immediately visible to Facebook audiences. For example, if the description of a page contained the word “election”, it was removed from the corpus.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine distributions of content per category and reveal posting patterns of non-political pages. We also extracted subsets of data that share content from official and unofficial pages of top presidential candidates, and summarized relevant metrics using Python and Pandas, which can process large volumes of data. Topic modeling using latent derelict allocation (LDA) was also performed to provide a top-line understanding of the content being shared by these pages.

Results and discussion

Non-political pages in the 2022 Philippine General election discourse

Out of the 96 high-volume page categories posting about the 2022 Philippine general elections, 65 categories are labeled as political while 31 categories are labeled as non-political. The top 20 page categories based on number of posts are shown in Table 2 below. In general, the top number of posts engaged in election-related conversations come from categories where political and partisan content are expected to originate, such as Facebook pages of celebrities and influential individuals (e.g. ‘PERSON’), media organizations (e.g. ‘NEWS_SITE’, and ‘MEDIA_NEWS-COMPANY’) and political/advocacy groups (e.g. COMMUNITY_ORGANIZATION, NON_PROFIT).

Our research is primarily interested in the involvement of non-political pages that appear non-political (see Table 3). “ACTIVITY_GENERAL” was the top category under non-political and appears to be a catch-all for interest-based pages that may include official and fan-made pages of celebrities, meme pages, and brand pages. It is noticeable that less than half, or 23,364 posts remained under this category, after removing pages that contained election-related terms in their page name and description. Other non-political page categories include interest-based pages

relating to entertainment which have noticeably fewer, yet still sizable amounts of posts. Similar to pages categorized as political, there is no strict adherence to the categories in terms of the actual identity and content of the pages, and identities and ownership of some pages are unclear.

The declared page categories, page name, and page description of pages included in the analysis make it appear that they are primarily disinterested and unrelated to the elections. However, their posting activity indicates otherwise. Despite being non-political pages, we observed that post volume ramped up as the election season drew closer. From May, posting activity steadily increased and peaked during the month of official filing of candidacy in October (see Figure 1).

Peaks in the day-to-day posting activity of these non-political pages were also observed during news events centering on elections, mainly during announcements of candidacy (see Figure 1). This is evident during October 7, the day before the deadline of official filing of candidacy and Leni Robredo’s announcement of her presidential bid, the uptick in posting during September 22 when Isko Moreno announced his intention to run for president and on November 13, when Sara Duterte officially ran as Vice President via substitution. There was also a surge in posting activity during Jessica Soho’s presidential interview. In general, peaks were observed during election-related events, providing evidence that non-political pages, despite their seemingly non-partisan appearance, are participating in election-related discourse.

Non-political pages and their political sources and content

The volume of posts made by non-political pages during political events is indicative of their political activity. However, this is not just limited to posting about politics – non-political pages are also sharing partisan content in their timelines. Looking at the top sources of content shared by non-political pages [Table 4], official presidential candidate pages (e.g., iskomorenodomagoso) and support pages (e.g., teamlenirobredo) were part of the top sources of content shared by non-political pages, alongside pages of mainstream media organizations

(e.g., abscbnNEWS), prominent Philippine shopping malls (smsupermalls), and the public information office of the Philippine National Police (pnp.pio).

The official page of incumbent Manila Mayor Isko Moreno took the highest spot among presidential candidates as the most shared source of political content by non-political pages. His page is followed by the official pages of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., Vice President Leni Robredo, Senator Manny Pacquiao, and Senator Panfilo Lacson, respectively. Unlike news media and shopping mall pages, candidate pages are made primarily for political reasons, containing partisan materials that explicitly support and advocate for the candidates they represent, especially during election season. Non-political pages engage in the amplification of messages by political candidates, and audiences of these pages, who may have initially liked these pages for reasons unrelated to politics, become captive of campaign materials they cascade.

Political actors can take advantage of the large audience base of non-political pages. Since these pages are packaged for special interest groups and topics, they can reach diverse audience segments and influence political fence-sitters. This is in contrast to the followers of political pages, who are more likely to have already formed their political opinion. In other words, non-political pages serve as venues for strategic political communication. Our calculations show that non-political pages had an average of 238,154 followers, reaching a peak of 16,914,920.

Looking at the pages sharing content from official and unofficial pages of candidates [Figure 2], our findings indicate that there are more pages sharing content from Isko Moreno pages, followed by Robredo- and Marcos-related pages. Here, we selected non-official pages that contained the name of the presidential candidates in their page names.

It is also noticeable that there are no pages sharing content from unofficial pages related to Lacson.

pages

Although there are no pages sharing content from unofficial Lacson Facebook pages, it appears that pages that share content from the official Lacson page have the highest average number of followers, indicating the potential reach of his official page posts as they get shared by non-political pages. As shown in Figure 3, the average number of followers of the pages that share Lacson’s official content on Facebook towers over the other candidates.

unofficial candidate pages

When it comes to posts, interactions averaged at 2,025, with one post even scoring 903,717. These numbers tell us about the activity of non-political page followers, which can be engaged to gain more visibility on the platform. Overall, there are more posts shared from unofficial candidate pages than their official pages (except for Pacquiao). Among the top presidential candidates, Robredo had the most number of posts from her official and unofficial pages shared by non-political pages, followed by Moreno (see Figure 4).

pages

In terms of interaction, posts shared from Pacquiao’s unofficial pages garnered the biggest average interaction score, towering over other candidates. Noticeable in the graph (see Figure 5), however, is the low average interaction scores garnered by Lacson, even though some of the largest non-political pages are sharing content from his page.

by nonelection-related pages

The findings above are indicative of the reach and engagement present in non-political pages as they share content from partisan sources – from official candidate pages to campaign support pages and other unofficial candidate pages. It is also interesting to note that non-political pages shared more content from unofficial candidate pages. Compared to official candidate pages, content from these sources can be more affective and emotion-driven, and tend to have stronger partisan framing of political agendas in their support for a candidate.

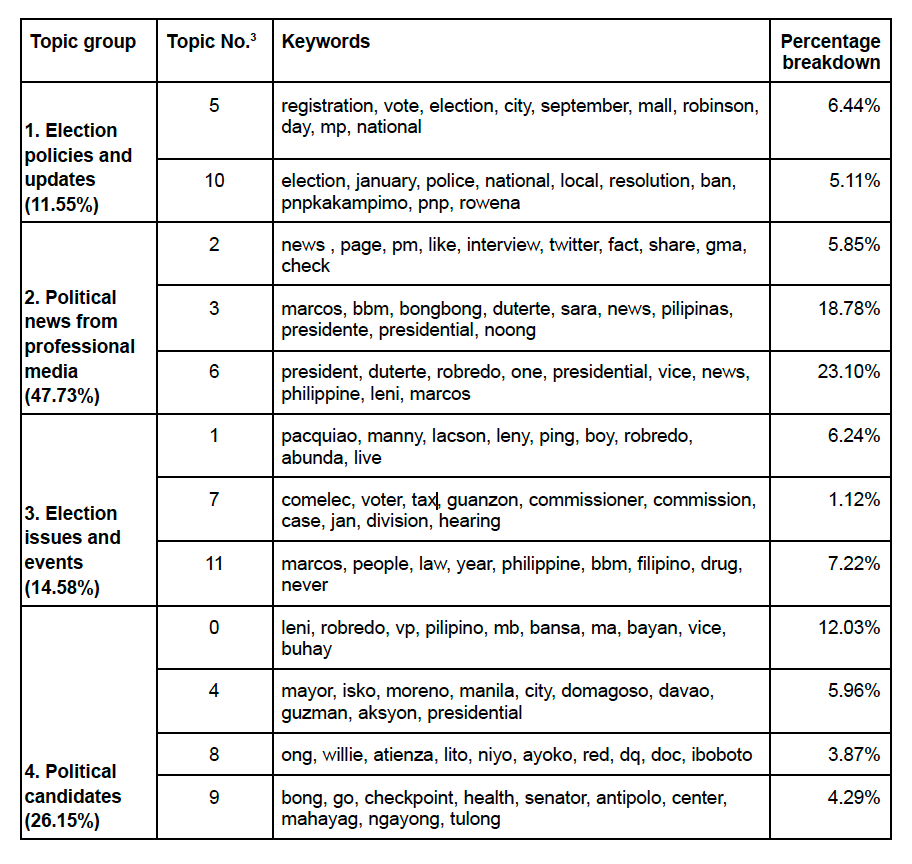

To get a top-line understanding of the political topics shared by these non-political pages from different sources, topic models were generated. Upon examination of the keywords, we found that the topics can be clustered into four groups (see Table 5). The first topic group (11.55% of the corpus) contains keywords related to election policies and updates, and it can be inferred that posts under these topics were related to election policies and voter registration guidelines shared by government institutions (e.g., COMELEC, PNP) and their partners (e.g., SM

Supermalls).

The second topic group, which is the most dominant in the corpus (47.73%) contains topics with keywords related to political news from professional media (e.g., ABS-CBN News, Manila Bulletin), which can be understood as posts that share news articles about the elections and political candidates, evident in the co-occurence of political candidate names and the word “news.”

The third topic group (14.58% of the corpus) contains topics with keywords about election issues and events such as interviews and cases. The fourth group, which is second-most dominant in the corpus (26.15%) contains topics containing the keywords specific to political candidates. Topic groups 1 and 2 may have emerged as non-political pages disseminated election-related information, but topic groups 3 and 4 can be a result of non-political pages engaging in partisan behaviors online, given the topics and keywords clustered under them.

The topic numbering below is based on topic outputs generated through latent derelict allocation in Python.

Non-political pages, political propaganda, and disinformation

While it is difficult to fully operationalize the tracking of propaganda and disinformation in social media, a good indicator of it is “Coordinated Inauthentic behavior.” Facebook’s Nathaniel Glecher defines this as a phenomenon wherein “groups of pages or people work together to mislead others about who they are or what they are doing.” One of the methods to identify coordinated inauthentic behavior is through “coordinated link sharing behavior,” or when multiple Facebook pages repeatedly share the same posts in an “unusual short period of time.”. We identified 61 pages engaging in this behavior sharing 634 unique links. Most of the links are shared from pages with non-candidate-related keywords.

However, those that are candidate-related emanated from Lacson-related pages or Pacquiao-related pages (see Table 6). Interestingly, while having the most shares, Lacson-related pages shared only 7 unique links across 28 unique pages multiple times. Conversely, Manny Pacquiao-related pages had 100 unique links shared only across 9 unique pages. Upon inspection, these identified coordinated pages pose as entertainment pages sharing relatable quotes about life, romance, and heartbreak.

To deep-dive into coordinated link-sharing behavior, we looked into simultaneous posting of content among pages. By determining time points with the highest instance of simultaneous posting down to the seconds-level, we were able to reveal indicators of inauthentic behavior from non-political pages. To illustrate, we found 51 posts from different non-political pages posting the same content at exactly 11:42:56 on September 29, 2021. Shown in Table 7 are 10 Timestamps with the highest volume of simultaneously uploaded posts. Upon inspection, we found the same set of posts being uploaded by different non-political pages, all of which contain support for Lacson. Similar to the identified coordinated pages mentioned above, these pages masquerade as accounts that share content related to mental health, wellness, romance, heartbreak, motivation, and self-help but display inauthentic posting behavior related to politics and the elections.

TABLE 7. Posting timestamps and number of simultaneously uploaded posts

Aside from coordinated inauthentic behavior, we found evidence of disguised propaganda when we examined page names and corresponding usernames. To reiterate, our dataset is composed of pages with page names and page descriptions that appear non-political, i.e., their names did not contain any word or phrase that are related to politics or to the 2022 presidential elections. However, we found that pages whose page names appear neutral or interest-based (e.g., gaming and music), but with Facebook usernames revealing their hyper-partisan identities. In particular, we found a number of posts from pages with usernames containing the words “Duterte” and “Marcos” to be sharing content from official and unofficial pages of Marcos Jr., while disguised as gaming and music pages.

Malicious actors take advantage of the “limited identity cues,” says scholar Judith Donath, in digital media environments to manipulate audiences. In the case of cloaked political pages, manipulation is done as political pages take on non-political identities to reach unsuspecting audiences, distribute political content, and amplify political agendas. Not only are the sources of these pages unknown and hidden, but they also impersonate non-political identities to build connections with non-political audiences.

Conclusion and recommendations

Our report has provided evidence of the role of non-political pages in the 2022 Philippine presidential election discourse on Facebook. In particular, we found non-political pages actively engaging in political activity and election-related conversations based on their posting behavior in the run-up to the elections. Our study has also presented how non-political pages are not just engaged in activities beyond those that can be considered politically neutral (such as sharing election information-dissemination); they actively engage in online partisan behaviors by sharing content from partisan sources, and participating in partisan discourses online. Finally, we have shown evidence that non-political pages can be used for disinformation through the obfuscation of their actual, partisan identities, and coordinated posting behaviors.

Given the role and influence of non-political pages in the election discourse, we offer the following insights for media, platforms, civil society, and voters:

Anonymity with accountability. The “limited identity cues” present in social media platforms allow users to remain anonymous as they engage in discourse online. Anonymity affords individuals the freedom to engage in democratic discourse as it allows them to reveal their true beliefs without fear of isolation or social pressure. However, it also allows users to engage in deceitful behaviors due to lack of accountability (Asenbaum, 2018). Anonymity thus becomes an abusive user’s license to engage in malicious behaviors. On Facebook, pages engaging in abusive and malicious behaviors can be taken down, but they can freely reemerge without any real consequences. The anonymous page administrators remain obfuscated and able to create more cloaked pages. Platforms must thus reconsider how to hold users accountable for any abusive action online, without removing the affordance of anonymity that enables others to freely and creatively engage in democratic discourse.

Investigating disinformation outside of the traditional information sources. Aside from looking into news or news-like genres, we recommend fact-checkers, media, and researchers of disinformation to investigate spaces that appear neutral or non-political, especially since these pages are able to reach audiences that are not primarily interested in politics or engaged in political discourses. As shown in our research, coordinated, inauthentic behavior, and disguised propaganda are also enacted by pages that appear to be non-political. Platforms that have non-political content genres such as YouTube can be examined to see how disguised propaganda operates in these spaces.

Non-political Facebook pages can be used for disinformation through the obfuscation of their actual, partisan identities, and coordinated posting behaviors.

Increasing discernment and criticality of our personal information environments. What appears to be non-political online may actually be venues where political propaganda is distributed and amplified. Digital literacy and voter education programs can be enhanced by highlighting how seemingly non-political pages can also be used to spread disinformation and manipulate audiences. Evidently, this issue is rooted in and can be addressed by larger institutions, but by constantly retooling current media literacy programs with the emerging practices of disinformation in social media, users can become more critical as they engage with different actors in the platform. – Rappler.com

Jon Benedik Bunquin is an assistant professor at the Department of Communication Research, University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication. He uses quantitative and computational methods to study how networked environments shape the communication of political and scientific information. He has presented and published work on the political communication networks of the Filipino youth, networks of online social movements, political participation, and science communication in various local and international conferences and journals. He earned his MA Communication and BA Journalism (cum laude) degrees from the University of the Philippines.

Myrnelle A. Cinco is currently aiding the Department of Communication Research of the University of the Philippines Diliman College of Mass Communication in a number of research projects. She is working as a research assistant for an international nonprofit organization working on human rights. She has a background in data analytics, data science, and research and previously received her Bachelor’s degree in Communication Research from the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Julienne M. Urrea is an English and Literature instructor at the University of the Philippines Rural High School, a basic education laboratory unit of the University of the Philippines Los Baños. She is a graduate student at the Department of Communication Research, UP Diliman College of Mass Communication.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Cybermisogyny violates human rights](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/06/Cyber-misogyny-human-rights.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] Building Narratives: stories of greatness and windmills in Marcos Jr.’s campaign video](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/05/Narratives-marcos-windmills-May-18-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINYON] Takoyaki tattoo at ang business model ng pang-iinis](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/20240410-Takoyaki-tattoo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.