SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

WASHINGTON – Google is a powerhouse in Washington with deep pockets and close ties to the government regulators who oversee the company’s ambitions from advertising to artificial intelligence.

But the search giant’s political savvy hasn’t spared the company in recent weeks from stinging attacks from Democrats and Republicans, including President Donald Trump – a turn of fate that now threatens to saddle Google with months of continued scrutiny and new threats of regulation.

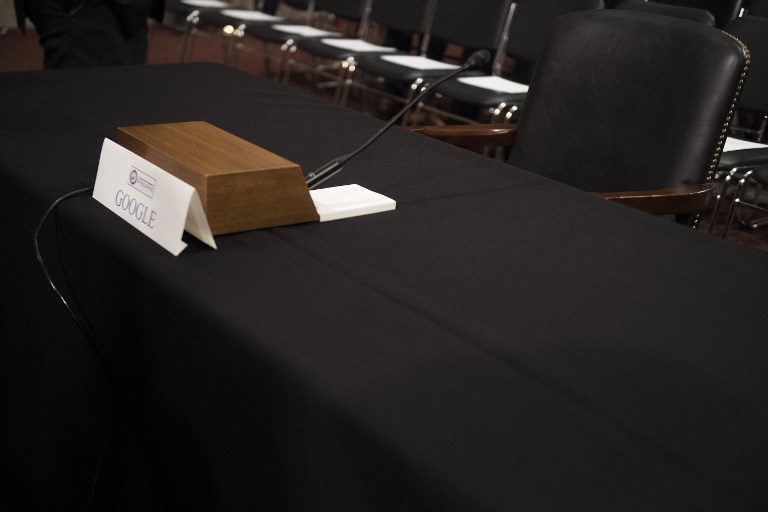

In August, Trump accused Google of manipulating search results to show negative stories about him. A week later, congressional lawmakers rebuked the company for failing to send one of its top executives to testify at a hearing alongside Facebook and Twitter. The Senate Intelligence Committee even left an open chair to highlight Google’s absence, which lawmakers like Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, called an “outrage.”

Even after the hearing concluded, the criticism hasn’t subsided. Now, Google faces the potential that lawmakers could ramp up their attacks – not to mention their demands for a top Google executive to appear soon on the Hill.

“Google is sadly mistaken if they think they’re off the hook after being a no-show,” Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., the top Democrat on the committee, said in a statement Friday.

The shifting of Google’s political fortunes ends a period of relative calm for the company in Washington. Lawmakers until recently had focused much of their attention on tech giants like Facebook, probing its recent privacy mishaps and efforts to combat Russian agents that spread propaganda online.

For Google, its new political headache could result in tougher scrutiny of its business practices, from its efforts to police sites like YouTube for abuse to its ambitions to launch a special search engine in China. Warner, for example, said he had questions for Google about China as well as its revelations of Russian accounts it found on YouTube and disabled earlier this year.

“They owe it to Congress to show they’re serious about protecting their users and our democratic values here at home and across the globe,” he said.

A Google spokeswoman said the company over the past decade has “actively engaged on both sides of the aisle, including testifying five times to Congress over the past year, as well as providing numerous briefings to members of Congress. We know there are many topics facing our industry and we will continue to work closely on them with policymakers in Washington D.C.”

Google long has counted on a sprawling Washington operation, which spent nearly $11 million on lobbying during the first six months of the year – a record among tech companies, federal ethics reports show. It recently has retooled that policy team, including the July promotion of Kent Walker, its longtime general counsel, to senior vice president of global affairs, overseeing the search giant’s policy efforts worldwide.

Since 2017, Google also has hired a former congressional staffer with ties to national Republicans, a former top policy aide from GE and a national security expert who served under President Barack Obama.

Walker and his team quickly found themselves on the defensive. Trump last month alleged Google search results had been “rigged” against him, and his administration at one point threatened regulation. Last week, the Justice Department said it would probe whether tech companies are “stifling the free exchange of ideas” online. And Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, recently added his high-profile support to calls for the government to reopen its antitrust probe of Google, which Washington closed without seriously penalizing the company in 2013.

But the hearing Wednesday laid bare the broad political anger toward Google. The company initially had offered Walker to testify in front of the Senate Intelligence Committee alongside Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg. Lawmakers rejected that idea, insisting on Larry Page, the chief executive of Google’s parent company, Alphabet, or Google CEO Sundar Pichai. Google declined the request.

During the hearing, Warner blasted Google for its “structural vulnerabilities,” including the fact that conspiracy theories often float to the top of search results. Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., lambasted Google as “arrogant.” And fellow GOP Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas criticized Google for canceling its work with the Pentagon on a drone program because of employees’ objections.

Google’s allies said the hearings featured plenty of “grandstanding,” in the words of Rob Atkinson, the president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, a think tank that counts the search giant as a board member. But Atkinson said that Google still should have dispatched its leaders to Washington.

“You have to feed the beast,” he said. “At the end of the day, it’s better to be there and engage than it is to not be there and hope you avoid some tough questions. I might not have said that three years ago, but it’s a different environment now. The sharp sticks are out on both sides of the aisle, bashing tech.”

For his part, Walker met privately last week with members of the Senate Intelligence Committee, a Google spokeswoman said. After the hearing debacle, Google is also deliberating how executives including Page and Pichai should approach the nation’s capital, according to two people familiar with the company’s thinking.

Senate lawmakers do not plan to subpoena Google to testify, a spokeswoman for Intelligence Committee Chairman Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C., said Friday. In the House, however, Google still faces pressure to send a top executive for a hearing to probe the company’s powerful algorithms. A hearing isn’t scheduled on the Energy and Commerce Committee, but its chairman, Rep. Greg Walden, R-Ore., “has specifically said he’d be interested in hearing from Google,” a spokeswoman said.

To close watchers of the tech industry in Congress, those demands are likely to intensify – and executives at Google and around Silicon Valley must rethink their historic reluctance to engage the Capitol or risk unintended consequences, said Sen. Ron Wyden , D-Ore., a member of the Intelligence Committee.

“It makes sense that tech companies would rather send a lawyer than a tech person to talk to Congress,” he said, “but it would be useful for tech companies to get to know Washington to make sure that the short-sighted tech policies up here don’t gain more purchase.” – © 2018. Washington Post

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.