SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Social media has revolutionized the way we interact, arguably, for the better – democratizing power and giving voices to long marginalized communities.

Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have broken information monopolies and curtailed censorship around the world by making it easy to connect with anyone. That’s changing the way we think, the way we work and the way we play.

At the same time, this unprecedented level of exposure comes with new hazards which we all need to manage in order to safeguard the quality of our online experiences.

The current dangers of social media are increasingly well documented. Recent media coverage brought public attention to online bullying and other abusive behaviors. Another recurring theme of our increasingly online lifestyle is data privacy.

Yet there is another, less well understood social media phenomenon which threatens the experience of all social media users. Some corporations, interest groups, and governments are mobilizing fictitious social media resources at scale to disrupt other legitimate uses of these platforms.

Left unchecked, practices like this could turn a platform like Twitter into a wasteland, discouraging people from participating and limiting the potential power of the crowd for good.

People on social media, bloggers, journalists, online marketers and anyone else looking to spread a message online need to be aware of this threat and learn how to deal with it.

Launch of #SmartFREEInternet

At 11 am on Friday, September 26, 2014, PLDT Chairman Manuel V. Pangilinan announced a promotion to provide free Internet access through the country’s largest telecommunications companies Smart, Talk’N Text, and Sun Cellular. From now until November (later revised to January), certain customers can access up to 30 megabytes of data daily without incurring the normal charges. The promotion is targeted to pre-paid customers, a fiercely competitive market in the Philippines.

Following Pangilinan’s announcement, Smart launched a social media campaign using #SmartFREEInternet. The company took the usual steps of promoting the hashtag and campaign messages through official as well as brand ambassador accounts. That was when things got interesting.

The following day, Di9it’s Carlo Ople, connected to an agency that services Smart, published a blog post criticising what he described as an organized effort to mislead social media users.

“You are deceiving your consumers with fictitious accounts,” wrote Ople. “You’re making fools out of them by making them feel they’re talking to real people when they’re not. This is digital marketing without creativity and with no soul. Instead of doing stuff like this just come up with a better offer, inform everyone about it, and let the consumers decide.”

Reach Social, Rappler’s data analytics arm, investigated Ople’s claims and began to track both #SmartFREEInternet and the sudden counter-campaign hashtags.

Timeline of disruption

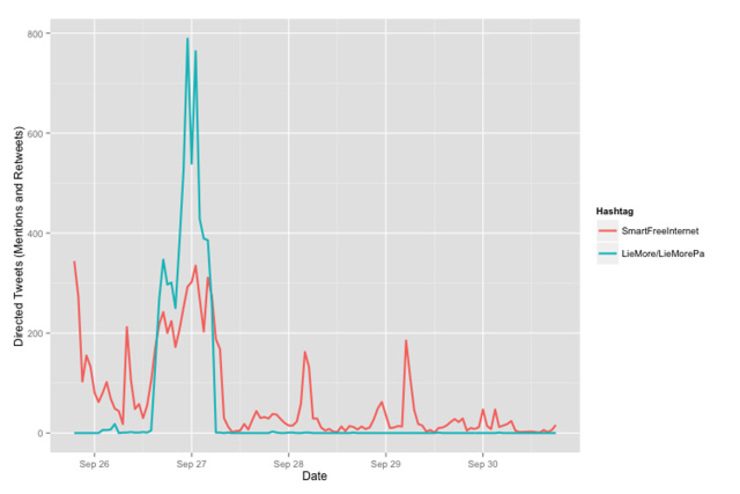

Hashtags #LieMore and #LieMorePa were by far the two most prevalent hashtags in the counter-campaign against #SmartFREEInternet. Reach analyzed tweets containing any of those three hashtags from September 25 until October 1, 2014.

A clear story emerged: shortly after the promotion launched, an intense and short-lived burst of negative tweets containing the hashtags #LieMore and #LieMorePa appeared (see Timeline below). It soon became obvious that this was not a genuine backlash against #SmartFREEInternet. But it was enough to drown Smart’s efforts.

By Saturday evening, September 27, only one day after the promotion launched, Smart had stopped most of their campaign activities on Twitter.

The counter-campaign hashtags #LieMore and #LieMorePa exhibit some interesting behavior. First, it produced an acute spike of directed messages with such frequency that it temporarily derailed Smart’s promotion.

Tweets from accounts using #LieMore were directed at a mixed group of Twitter accounts. Some of the targets had used #SmartFREEInternet in their tweets but also many did not. The majority of targets did not follow or publically message each other.

One thing that did tie these accounts together was their demographic, which strongly overlapped with the pre-paid market Smart was appealing to. This negative blitz, whether intentional or not, effectively disrupted Smart’s messaging offer.

Second, almost none of the tweets containing #LieMore or #LieMorePa also used #SmartFREEInternet. Intuitively, this seems like an error because piggybacking on the primary hashtag of the Smart campaign would give access to the same audience. However, including #SmartFREEInternet would also help make that hashtag trend.

Third, many of the tweets that disrupted the Smart conversation were deleted soon after – a seeming attempt to erase the actions taken (and why many call this black ops).

3 different groups

The Twitter accounts sending the messages fall into 3 distinct categories. The first category is a series of accounts created explicitly for this counter-campaign. These accounts had a very obvious profile: an unusually high ratio of outbound to inbound traffic, recent creation date, spare profile information – leading to the conclusion they are bots. By the end of the weekend, most of these accounts were suspended just like @ClaireAmweg, which Ople used as an example in his blog.

The managed accounts also tweet infrequently but at regular intervals, usually between one tweet every 3 days to two weeks. It can be difficult to spot these accounts based on their status updates because negative messages such as the #LieMore and #LieMorePa tweets are deleted quickly after the campaign is over.

However, the remaining status updates are a mix of positive messages about a competing brand and filler content used to make the accounts appear legitimate. The content of the unbranded status updates ranges from material scraped from Wikipedia articles, to retweets of a single popular account, to banal but common expressions. (How many times has someone tweeted “love hurts, live more” or any combination of those words?)

They also have followers, and usually don’t follow more than twice the number of people following them. In the case of #LieMore, they usually had around 200 followers but sometimes up to 300. While it seems unlikely anyone would follow these accounts, a manual review of obviously fake accounts shows they probably acquire followers in one of two ways.

First, they rely on the fact that some accounts will follow back no matter what. Second, and more telling, is these accounts often follow each other. After identifying a single managed fake account, it is easy enough to connect the dots to many others.

It’s very clear these accounts are created and maintained in bulk. A group of managed fake accounts exhibit some similar patterns. Besides following each other, they will also follow one or two of a handful of large legitimate accounts. They tend to tweet at around the same time and post at similar intervals. They were mostly created within a month of each other, but sometimes up to a year or more apart.

The third type of account to tweet #LieMore and #LieMorePa are legitimate accounts who picked up the hashtag after it was launched en masse by bots and fake accounts. Some of these accounts were directly targeted by the counter-campaign, but others simply saw the hashtag and started using it. Their grievances and complaints appear to be genuine and their behavior is not abusive.

As consumers of telecommunications products, this third group has the most to lose from the disruptive counter-campaign because they were cut off from a potentially gainful dialogue with companies they are purchasing services from. Regardless of whether they would be persuaded by Smart’s promotion, this group of people were intentionally prevented from gaining information about their choices in service operators.

Communities

The image below is a social network diagram, in which each circle represents an individual Twitter account. The size of the circle represents how many messages were directed to that account, and circles which are closely tied together are the same color. The line between the circles represents directed messages, the blue lines contained the hashtags #LieMore or #LieMorePa, and the yellow lines contained #SmartFREEInternet.

The group in the bottom left corner contains Smart’s official account @SmartCARES, which was used to announce the promotion but did not engage in any back-and-forth conversation with other Twitter users. Smart is completely disconnected from the larger central group, which is composed mostly of accounts which were targeted by the #LieMore and #LieMorePa bots. As mentioned above, some of these accounts were using the #SmartFREEInternet hashtag and some were not. Most of these accounts fit the demographic for pre-paid plans, the target market of this promotion.

In a move taken directly from real world guerrilla warfare (what the communists called ‘surrounding the cities from the countryside’), the bots and fake accounts surrounded and isolated the central group.

In the social network diagram, these accounts are the center of the small groups encircling the the central community. They are also scattered through the legitimate accounts. Although their messages were probably less meaningful, they were just much louder.

Smart’s accounts didn’t address the counter-campaign directly (and perhaps even if they did, it wouldn’t have been able to match the volume). That allowed the #LieMore counter-campaign to hijack the conversation and to separate Smart from its target audience.

What can you do?

Be vigilant. The age of social media devolves great power directly to the people, but it requires a level of awareness and skepticism. If you look at some of the bots’ and fake accounts’ tweets, there is outright disinformation in their responses to real people.

Learn to recognize behavior like this and shine the light of day.

Like in the real world, hold individuals, companies and nations accountable for their actions – both offline and online. – Rappler.com

Reach is the data analytics arm of Rappler. It uses an in-house tool developed to monitor the growth of communities and the spread of information and emotions on social media.

Business people image via ShutterStock.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.