SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

One of the biggest stories of the year for social media was how the primary platforms – Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube – managed disinformation during the US presidential elections. In the previous one in 2016, Facebook had been effectively manipulated by foreign state actors to influence the results in a certain way. All eyes were on them – and the other platforms – in 2020 to see if things had changed.

The short of it: they were, at the very least, generally more proactive, although to say that the solutions were perfect is a stretch.

In 2022, the Philippines, called a petri dish for information operations, will hold its own presidential elections. What happened in the recent US elections foretell what the social media landscape might be like in the upcoming Philippine polls. It’s important that we keep in mind these new learnings, where their policies stood, and where we can keep pushing them to improve the current digital ecosystem in preparation for 2022.

YouTube’s lax policies

Of the 3, YouTube was seen to have the softest stance on keeping misleading and outright false information on their platform.

It wasn’t until more than a month after the US elections that it started removing channels – 8,000 of them – with false election claims. Their justification? They allowed the misleading videos to persist to allow for political discussion. As a result, videos that supported Donald Trump’s campaign claiming electoral fraud remained on the platform, even if there had never been evidence of such.

Transparency.tube, an independent research project cited by The Washington Post, found that unfounded claims of election fraud had about 137 million views between November 3 and 10.

A Pew Research study found that 73% of viewers believe that news found on YouTube is “largely accurate.” Having a talking face on the platform, delivering the news, gives a video authoritativeness and legitimacy.

YouTube started removing the channels on December 9 when it felt enough states had verified Biden’s win.

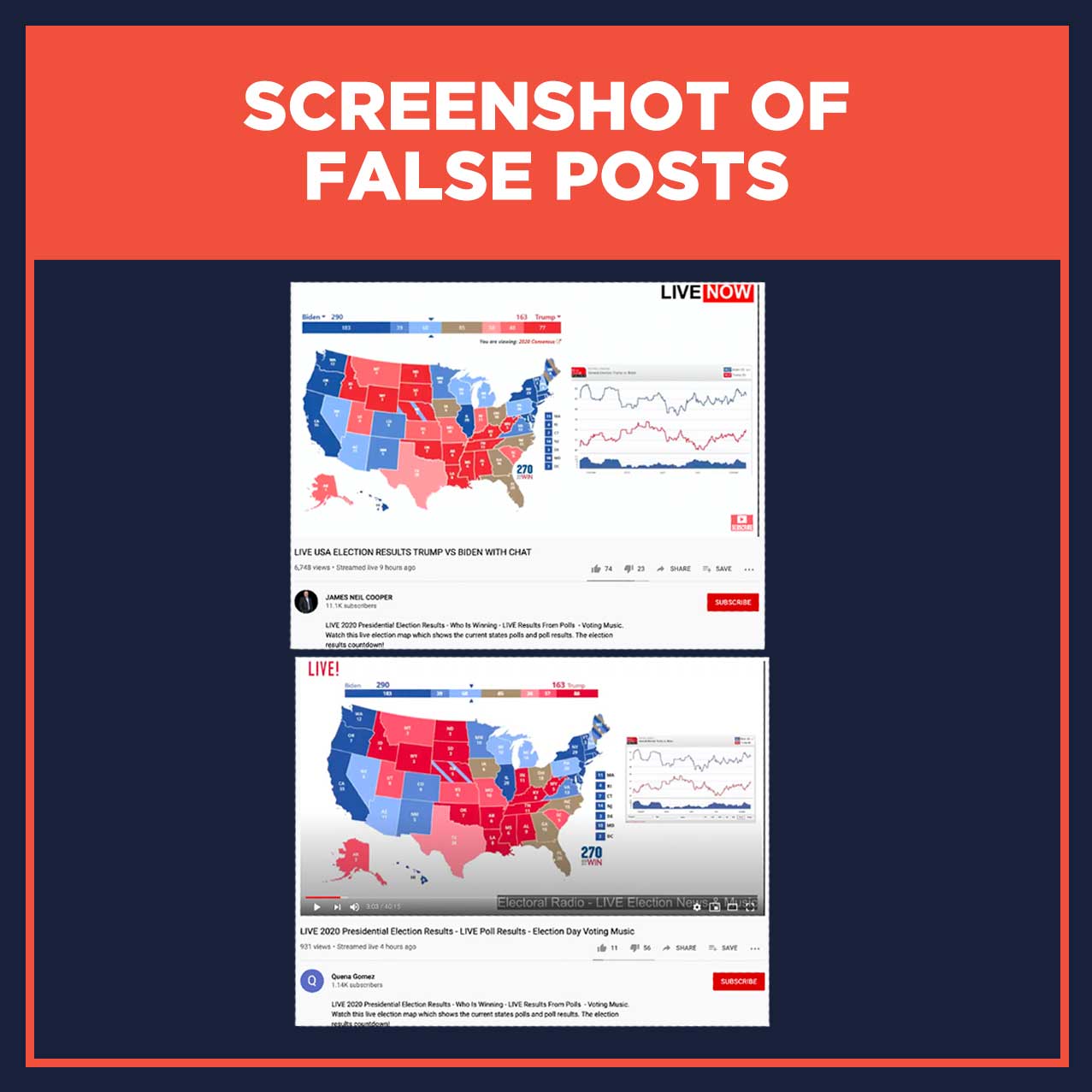

Videos claiming that Trump won, along with a fake election counter, pictured below, also fell through YouTube’s net:

YouTube, contesting the accusations of laxness, said that the most authoritative news outlets get recommended in their system. However, some videos – such as one that claimed Philadelphia had rescinded its call for a Biden win – had spread outside YouTube and got shared through private Facebook groups, according to Vice.

The far-right channel One America News Network (OANN), which had been posting videos on baseless claims of electoral fraud as Trump had been, was suspended in late November but for a different violation: COVID-19 misinformation. YouTube is selective on what types of false content to act on.

Given these instances, YouTube could become a safe haven for disinformation as Facebook and Twitter remain under closer scrutiny. The spotlight needs to be cast on YouTube as well.

Are labels enough?

The official numbers from Facebook: 265,000 posts removed or blocked for violating policies against voter interference and 3.3 million ad submissions blocked. Its key moves included labeling election disinformation such as Trump’s baseless claims of electoral fraud, yet the posts were still shared widely – similar to Twitter’s case.

Twitter was a little more aggressive, preventing some 400 false posts – some from Trump himself – from being shared or liked. About 300,000 tweets were also labeled for disinformation, which showed a user a warning before it can be shared.

Twitter reported a 29% reduction in shares for the false posts because of the pre-sharing warnings. However, a significant number of tweets from Trump baselessly claiming electoral fraud were still visibly being shared and liked in the days after the elections.

Even with the labels, the disinformation continued to spread. Those already part of a certain echo chamber kept seeing the same content, and a tiny label seemed puny relative to the relentless, emotion-stirring posts made by Trump himself.

It’s not a stretch to say that like-minded politicians will borrow the said strategy in the Philippine elections. Keep making noise; if the posts keep spreading anyway, who cares about a label?

According to internal Facebook discussions reported by BuzzFeed as well, Facebook data scientists found that the labels decrease the reshares by around 8%. However, because “Trump has SO many shares on any given post, the decrease is not going to change shares by orders of magnitude.” The labels simply aren’t effective enough to stop the tsunami of disinformation. Facebook says though that the labels are simply one part of their anti-disinformation efforts for the elections.

Facebook’s collective efforts though have not been enough to stop the spread of election disinformation, according to a December report by American non-profit Avaaz. The group found that leading up to the January Senate runoff elections, 60% of detected false and misleading posts still reached thousands without the fact-check labels.

The group, as reported by Venturebeat, found that the false posts with misleading claims on senatorial candidates, election recounts, and voter fraud still reached a combined total of 643,406 interactions. 112 of the 204 Facebook posts analyzed for the study didn’t have a fact-check label applied, meaning, a significant number of readers weren’t notified that what they’re reading was false.

The labels do help, according to MIT, as uncontested, unlabeled false posts retain a sense of authoritativeness for the reader. Posts with the proper labels lessen the impact. Given that, the labels make sense, but there’s still a lot to clean up, and there’s still a significant number of false posts flowing through Facebook’s filters.

Facebook reverses disinformation-fighting changes after the elections

For the US elections, Facebook made a change in its algorithm that allowed authoritative news outlets to be prioritized on the feed. This had something to do with what’s called the NEQ or the news ecosystem quality. They boosted the weight of the NEQ when it comes to what the algorithm recommends.

It feels like a logical change that would do wonders for democracy. For a while, when the votes were still being counted, the algorithm change helped increase the traffic for reputable sites such as CNN, NPR, and The New York Times. Meanwhile, highly partisan sites such as Breitbart and Occupy Democrats saw their traffic decline.

That change is gone now, with the presidential elections done. It shows that Facebook can prioritize more reliable news outlets if it wants to or if the polarized echo chamber hadn’t been so profitable.

The overall judgment from critics: Facebook and Twitter kept a closer eye on these elections than they ever have in the past, but a significant amount of disinformation is still slipping through. There doesn’t appear to be enough effort yet to break the echo chambers, with leaders and highly partisan outfits managing to keep their constituents listening.

YouTube appears to have had the worst run during the elections, given the platform’s soft stance on content with false information, allowing the misleading videos to stay afloat for about a month before eventually taking action. All for the sake of discussion, they said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.