SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

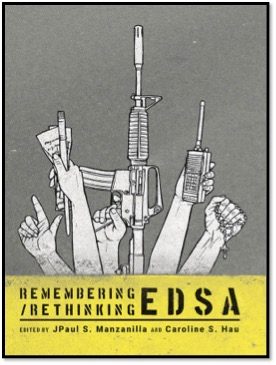

This is an exceprt from the essay “Being the Recollections of Ensign Faustino Sabado of the 5th Battalion Marine Landing team on what transpired between February 23 and 25 1986, as told in Bisayan to and roughly translated into English by Patricio N. Abinales,” which is part of Anvil Publishing’s new book Remembering/Rethinking EDSA, edited by JPaul S. Manzanilla and Caroline Hau.

We landed in Villamor Air Force Base around 5 am and were bused to the Marine Headquarters in Fort Bonifacio. In the additional briefing he gave us, Marine commandant Brigadier-General Artemio Tadiar said that our plan of attack had met some complications. After the Bishop of Manila, Jaime Cardinal Sin, called on “the people” to protect the rebels, he feared that civilians will be heading towards the outskirts of Camp Aguinaldo.

General Tadiar said we must strike before EDSA will be filled up with people as this will become a virtual defense shield for the rebels. He combined the 8th Marine Battalion and the 4th Marine Provisional Brigade to form two battalions under the leadership of Colonel Braulio B. Balbas, the Marines’ deputy commandant and head of the Combat Service Support Brigade. The attack force would be backed by enough firepower – one artillery unit with five 105-millimeter howitzers and V-50 and LVT6H assault tanks.

Once we are in the killing zone, one battalion will set up camp on the crossing of Ortigas Avenue and EDSA, while the other will move to the back of Camp Aguinaldo and probe weak points in the rebel defense. The artillery unit will set up their guns near Imelda Marcos’ University of Life campus.

After the briefing, we headed as a convoy towards Camps Aguinaldo and Crame. As we got into Ortigas, we saw vehicles parked on the road, their drivers clearly planning to slow down our advance. And they did! As we pondered our next moves – whether to run over the cars with our tanks, avoid them, or ask their drivers to move their vehicles out of our way. But no sooner had we settled down a group of civilians approached our position.

We immediately set up a defensive perimeter in case they would attack us. The group slowed down when they saw point our rifles at them. They realized that we were eager for the kill. Moreover, my comrades and I were getting irritated with what was happening. We had had very little sleep since we were ordered to leave our barracks in Zamboanga, and we had hardly eaten any decent meal! So, we surely were ready to break some heads and slash some stomachs!

Then what happened next was something totally unexpected.

Four nuns and 3 fair-skinned girls moved ahead of the group and briskly headed towards us. I looked at Caruso and said, “Unsa man ni?” He answered, “Ambot.” In our briefing, the officers told us that communists and oligarchs had decided to occupy a stretch of EDSA between the two camps, to protect the rebels from our attack. I did not know much about oligarchs (I knew they were rich, that was all), but knew the other one from the years we fought them in the mountains. But this? Nuns and mestizas? How could they be the communists and the oligarchs we were expected to eliminate as we closed into the camps?

Even our officers did not now what to do. A captain looked back at Colonel Balbas, his eyes inquiring if he should give the order to fire at the crowd. But Balbas ignored him, leaving our officers asking each other whether to fire or not.

Then things became more bizarre when the nuns knelt in front of us and prayed the “Our Lord’s Prayer,” followed by “Hail Mary,” and then the Rosary. We had a hard time keeping our stern and ice-cold dispositions. My buddy whispered to me, “Bai, are we supposed to pray with them?” I did not answer him because I too was feeling the pressure coming from their holy invocations. I was raised Catholic but had not gone to mass or confession for a long time now. I may have lost interest in the rituals but the fear of excommunication and being sent to Hell when I die was revived that afternoon. I continued to hold on to my rifle, but I was also strongly tempted to make the sign of the cross and even pray with them.

Then matters only became weirder. While the nuns were praying to (for?) us, the three mestizas began giving us flowers – one even inserted what I think were white roses into the barrel of a couple of rifles. While they were doing this, they kept imploring us not to attack the rebels because “We are all Filipinos! We all love democracy!” I was taken away by this lie – Filipinos do kill each other. And what of democracy? Did not the rebels violate democracy by not respecting the elections and trying to overthrow the President by the use of arms?

But I was also curious. This was the first time I’ve been physically close to a kastila-on (Spanish-looking, this is the other term we used to refer to these people), and now realized that their skins, their faces were indeed smooth as silk and as white as a bleached white t-shirt. And they smelled like sampaguitas! I whispered what I thought of their body odor to my buddy in Bisaya, “Bai, lain man ug baho na ilang paningot, humot kaayo!” He snapped back: “Domingo you idiot that’s perfume you are smelling not their body perspiration!” A diay?

Colonel Balbas finally ordered the tank commanders to prepare for the advance. We broke out our perimeter and moved to the back of the tanks – a routine maneuver that uses the tanks to protect us from incoming fire. As the tanks revved their engine, we suddenly heard voices at the front of our formation. We saw people shouting “Huwag na po! Kapwa mga Pilipino tayo! Huwag na kayong umabante! Tama na po!” in front of an LVT6H tank. Others were shouting “Cory! Cory! Cory!” and flashing the “L” sign with their hands, and still others sang “Bayan ko” or started to pray the Our Father.

A couple went to Balbas and their leader – this man in a yellow shirt claimed that he represented the leaders coordinating the crowd in EDSA and that he was passing on a message from them to the general. We could not hear what he whispered to Colonel Balbas, but when Balbas flinched and glared at the man, we knew it was not good. A stern Balbas broke away from the group and went straight to the lead tank commander ordering him to restart the engine. The commander obliged, and the LVT6H’s exhaust began to emit smoke. The other commanders also started their armor.

Instead of retreating, the crowd stood their ground. Then four men stood in front of the LVT6H and began attempting to push it back. This was a piteous act that made some of us laugh for obvious reasons: once that tank moves, these people are pulp. But the tanks never moved. I learned later that the tank commanders complied with Colonel Balbas’ command, but waited for the second – move forward! – that never came because the Colonel was again tied up by the group he was conversing with earlier.

So here we were, caught not in a cross fire, but hemmed in between God and the rich and beautiful. We kept waiting for Col. Balbas to issue an order to run over the vehicles and the people so we could proceed with our mission. But he never did anything. Instead, Balbas ordered the convoy return to Fort Bonifacio. As we retreated we saw the crowd clapping, the mestizas were blowing kisses at us, and the nuns were making the sign of the cross repeatedly.

Back at the Marine Headquarters, General Tadiar told us that we would try tomorrow again after a flustered Colonel Balbas explained what happened.

That night we had our first decent meal since we landed in Villamor.

Ensigns Faustino Sabado, Caruso Tecson, Sgt. Procopio Capio, and Capt. Percy Redoble are fictional characters, but the 5th Battalion Marine Landing Team to which they belonged is a real unit. It was one of the two Marine battalions whose mission was to attack Camp Crame on February 22, 1986. This never happened because of “people power.” The real stories of the Marines who were part of that assault team have yet to be written. Once these are finally put out for the public and the Marines to read, Ensign Sabado will disappear. – Rappler.com

Patricio N. Abinales is an OFW

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.