SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Billboards extolling the virtues of Vietnam’s ruling communist party now compete for space with international brands such as Heineken, Samsung, and Toshiba in this Southeast Asian nation of 90 million.

And here in the capital of Hanoi, bicycles and cyclos have given way to high-end scooters, taxis and personal autos as the preferred mode of transportation.

It is an incredible transformation that US President Obama will see during his ongoing visit to this country prior to his journey on to Japan for the latest G-7 summit.

But, as economic and geo-political interests draw the United States and Vietnam together, much unfinished business remains that must be addressed. This includes Vietnam’s failing human rights record and incomplete transition to a true market economy.

US President Barack Obama could well be a forceful, added voice for change in Vietnam. Some of the nation’s most vulnerable and persecuted lie languishing in prisons for daring to protest, to report freely or to pray as they choose. A failure by the US president to speak up on there behalf would be a tragedy and a betrayal of the values upon which the United States was founded.

The US-Vietnam relationship has steadily gathered steam since the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1995. That has been for the better as both nations have moved to address the lingering aftermath of their long conflict, from questions over Americans killed or missing in action to the consequences of Agent Orange use.

Trade already has grown significantly between the two nations.

And, both the United States and Vietnam have joined ten other Asia-Pacific nations in pursuing a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal that if approved by all signatories would cover 40 percent of global GDP.

A quickened pace of progress in US-Vietnam ties now comes amidst an increasingly assertive China on Vietnam’s borders and off its coasts. Vietnam understandably seeks strengthened US engagement in Asia to counter the rise of China.

Yet, China may well view the United States as a “paper tiger” in the South China Sea. The administration’s stepping back from its “red line” ultimatum in Syria has undercut perceptions of the steadfastness of US commitment. One result: Chinese fishing boats and island building now, military boats later.

In that context, Obama could well use a little Thatcheresque advice. “This was no time to go wobbly,” the then Iron Lady of Great Britain was said to have said to US President George H.W. Bush on the necessity of standing strong in enforcing an embargo against Iraq in the lead-up to the first Gulf War.

2 critical areas

Today, America’s president must also not “go wobbly” in pressing for continued change in Vietnam in two critical areas.

First, human rights, and religious and press freedoms must be high on the list, even as Obama considers lifting allowing military sales to Vietnam. US President Ronald Reagan once famously said from a walled Berlin, before the Brandenburg Gate, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” Obama, once known for his rhetoric, has a chance to underscore America’s commitment to speaking up for those in Vietnam under increased or longtime threat in their own quest to be free.

This includes Thich Quang Do, leader of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam. The 87-year-old religious leader has been under some type of state confinement for the last three decades due to his actions seeking greater democracy and freer expression.

In March, a Hanoi court sentenced blogger Nguyen Huu Vinh to five years in prison for “abusing democratic freedoms to harm the interests of the state.” His assistant Nguyen Thi Minh Thuy received a prison sentence of three years.

And just in the last weeks, the persistent lack of civil liberties in Vietnam was on full display when protests by residents concerned about the possible links between industrial waste and large scale fish deaths near their home were suppressed.

These and others voices should not be ignored in Obama’s pursuit of a deal and a legacy.

Second, Obama must continue to press Vietnam to move forward on its journey to a more market-oriented economy – one that keeps the faith in the ability of Vietnamese businesses and business leaders to compete freely and fairly. Ranked only 90th out of some 189 economies in the World Bank’s Doing Business report, Vietnam remains a story of two steps forward and one-and-one-half steps back.

Improving upon this ranking will require Vietnam to up its game and re-commit to the battle of the “little bric” – addressing the stifling bureaucracy and regulations, and clamping down on the state interventionism and corruption that hinders stronger business growth and strengthened U.S.-Vietnam commercial ties.

While a few landmark anti-corruption cases have captured headlines – a 2013 scandal that rocked state-owned Vietnam National Shipping Lines, or Vinalines, is a case in point – corruption has endured.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, which measures perceived levels of public sector corruption worldwide, ranks Vietnam 112 out of 168.

In a few months, the United States will elect a new president. That US president, whoever he or she might be, would be well-served by making clear that America’s enduring commitment to Asia includes not just defense ties but also support for human rights, religious and press freedoms, and commercial engagement.

Such an effort would be the benefit of both the peoples of the United States and of Asia and the Pacific. – Rappler.com

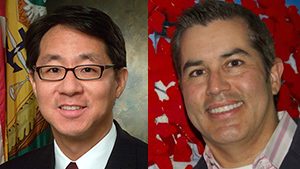

Curtis S. Chin, a former US Ambassador to the Development Bank, is managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group, LLC. Jose B. Collazo, a Southeast Asia analyst, is an associate at RiverPeak Group.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.