SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When I headed the Philippine Statistical Association Inc. (PSAI), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) invited the PSAI to conduct a third party evaluation of its Unconditional Cash Transfer (UCT) Program for Yolanda Victims. The emergency UCT program of UNICEF was aimed at providing quick relief to children and their families.

Ten thousand vulnerable families in Tacloban City and municipalities of Burauen, Dagami, Julita, La Paz, and Pastrana in Leyte were identified to receive $100 every month for a period of six months from February 2014 to July 2014.

The 10,000 household beneficiaries of the UNCT included households with pregnant and lactating women (PLWs), children suffering from moderate/severe acute malnutrition (MAM/SAM) or at risk of malnutrition, persons with disabilities (PWDs), persons with chronic illness, elderly persons, single female-headed households, child-headed households, households hosting separated children.

Dr. Celia Reyes, a PSAI lifetime member, and my esteemed colleague at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies who also serves as the Community Based Monitoring System (CBMS) Network Coordinating Team Leader, led the PSAI third party evaluation.

The PSAI conducted three survey rounds to collect information on a panel of households that received the UCT support. In addition, focus group discussions (FGDs) were also conducted to better understand the quantitative results. Key stakeholders, such as the implementing partners and cash distribution personnel, were also interviewed.

Of the 10,000 households, a stratified random sample of 499 beneficiary-households was selected for interviews for three survey rounds by the PSAI. The number of panel households interviewed for the three rounds is 484, thus attrition in the panel was quite minimal: attrition rate from the first survey wave to the second wave 0.82% final attrition rate was slightly over 1 percent (1.22%).

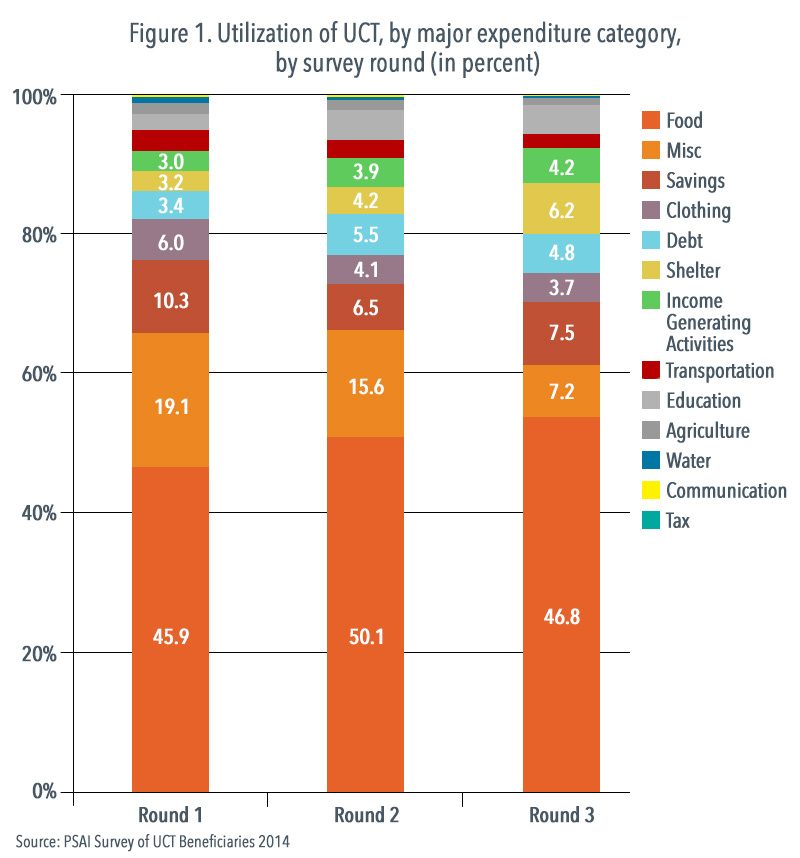

Food, savings

The PSAI observed that across the survey rounds, the top three uses of the emergency cash transfer received by households were on food expenses, miscellaneous expenses and for savings. (See Figure 1). Thus, the cash relief was able to help the beneficiaries smooth their food consumption, with about half of cash received spent on food.

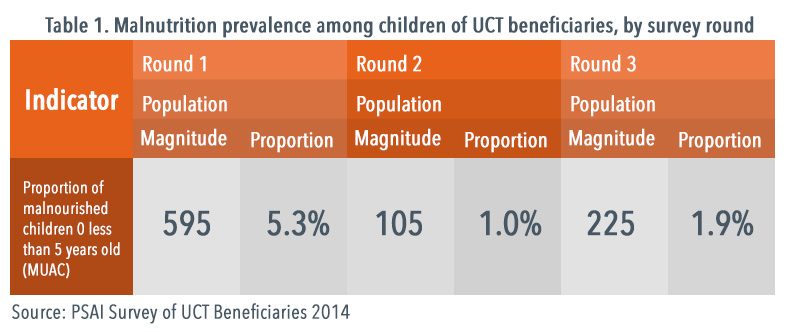

More than half of the cash was spent on food and this led to a significant decline in the malnutrition prevalence among children from 5% to about 1% to 2%.

Despite overall improvement in nutrition among children of beneficiary households, there were at least 21 children who were not malnourished during the first round of the survey were classified as malnourished by the third round of the survey. All of these children were located outside of Tacloban; these children were females, less than 1-year-old and have experienced hunger.

The emergency cash was also used to address some of the other needs of beneficiary households such as medicines, housing repair, livelihood and education-related expenses.

The FGDs revealed that many of the households spent money on vitamins, particularly for children. Savings also became increasingly an important use of the assistance. Proportion that went to savings was highest during the first round since families saved part of transfer to be able to buy materials for repairing their houses.

However, utilization for miscellaneous expenses and savings has continuously declined over time. Some households used part of the money to start or expand livelihood activities, such as pig-raising, sari-sari stores and food vending.

The amount of the cash was very significant compared to their usual income and allowed them to purchase items that they would not ordinarily be able to purchase. Majority of the beneficiaries recovered, either partially or fully, from the devastation of Yolanda after the six-month program.

The UCT was also used for household expenses relating to clothing, shelter, debt, income generating activities, transportation, education, agriculture, water, and communication. Expenditure on shelter almost doubled between the first and third rounds. Utilization for income generating expenses increased by 1.2 percent since the 1st round.

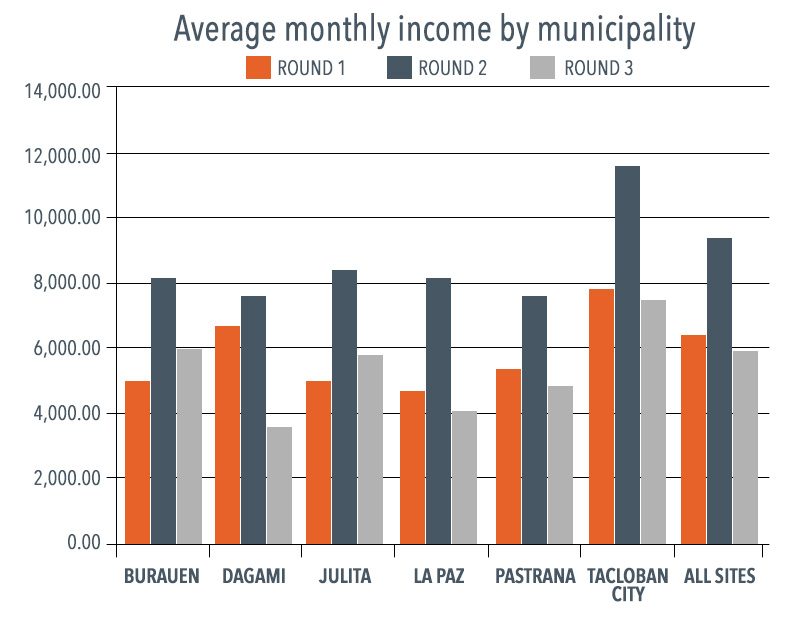

Average monthly income of beneficiary households across sites increased during the duration of the program, but drastically declined after the grant ended. In almost all sites, average monthly income after the program ended was lower compared to the period when the program started. The biggest reduction is marked in the municipality of Dagami where monthly income has been reduced by an average of at least P 3,076 per month.

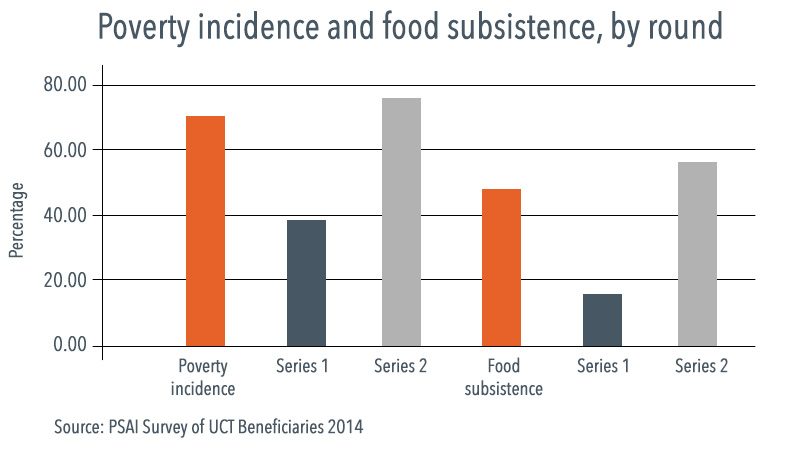

The UCT grant was twice that of average income of households, so this yielded a substantial effect on poverty incidence reduction. However, considering that the cash transfer constituted a significant portion of total income of the households, the end of the UCT program meant a significant reduction in the total income of the households.

This explains why some households fell into poverty during the third round.

The PSAI also noticed marked improvements not only in nutrition and income, but also in the areas of educational status of children, employment and housing.

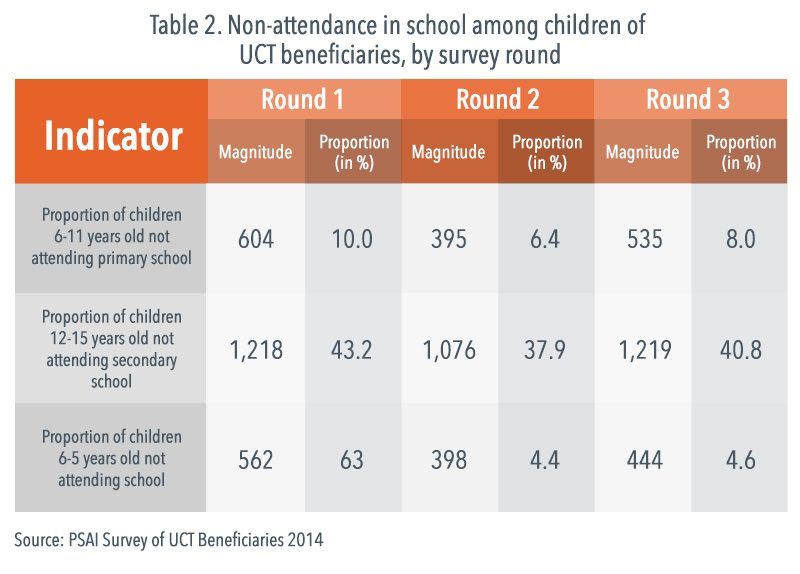

Table 2, for instance, shows that there was an overall improvement from round 1 to round 3, though there was a slight decrease in school attendance from round 2 to round 3.

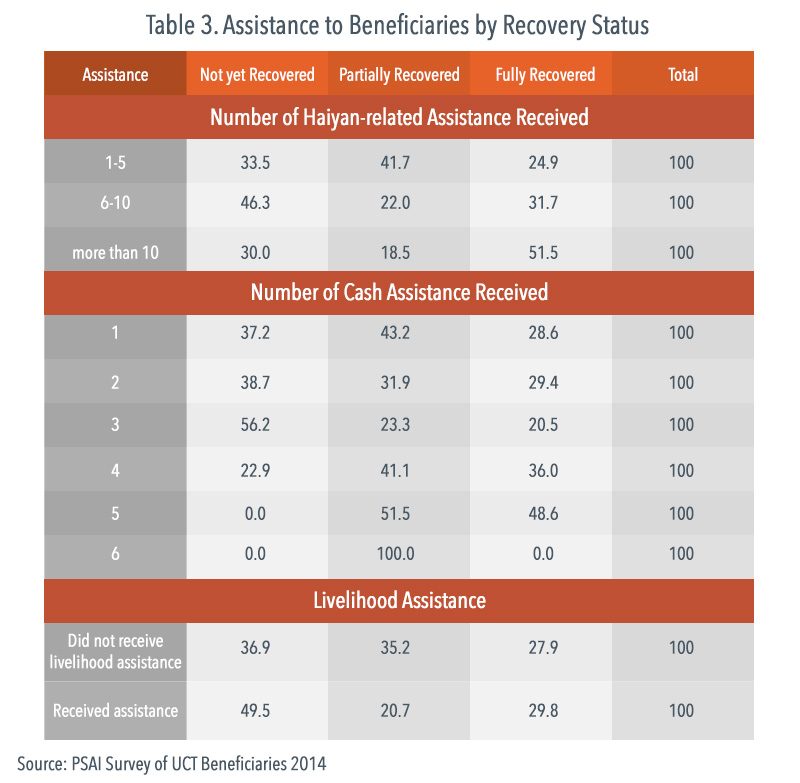

About 61 in every 100 beneficiary households have recovered from Super Typhoon Yolanda. Of these 61 households, about half (28 households) have fully recovered while the other half (33 households) have partially recovered.

In particular, those who used part of their cash transfer for livelihood or for savings were more likely to have recovered. Households received on the average about 5 assistance programs. More than half of the households who received more than 10 Haiyan-related Assistance have recovered.

The UCT assistance program has a number of learning lessons especially for future interventions to disaster victims. While most often people have a condescending view of cash assistance, (whether conditional or unconditional), it appears that the UCT has been a big help to beneficiary households.

The absence of conditionalities allowed the households to use the cash assistance as needed. Not all households, however, have fully recovered almost a year after Yolanda. Six months of assistance may not have been long enough for some households to get back on their feet.

The amount of P4370 per month over a period of six months is rather large compared to the usual income of the beneficiaries and cash assistance provided by other donors. This has allowed the beneficiaries to smooth their consumption of food and start/expand livelihood activities.

Costs, in terms of money and time, could be substantial on the part of the beneficiaries in obtaining the cash grants. More accessible distribution points could be considered for similar programs in the future. Distribution system for cash and non-cash transfers needs to be mapped out as part of disaster preparedness plans. Few and distant distribution points may pose significant costs on the part of the beneficiaries. Arbitrary distribution points may leave out some families in the communities.

Investments should clearly be made in having an updated list of residents in each area, with household and individual level characteristics that could be used as starting point for the list of potential beneficiaries.

Generating local level data such as the CBMS, can make communities and LGUs better prepared to cope with disasters (that are certainly recurring in the country). Well-defined criteria could be used in identifying beneficiaries to lessen reliance on skilled field workers to identify who should get into the program.

Coordination on the types of assistance can be improved. Greater coordination by LGUs, who have the main face of government in the field, can ensure that all affected households are covered by the different programs.

Alternative evacuation facilities should be identified. Return to normal routine, especially going to school for children, helps with the recovery process. Psychosocial impact assessment of disasters, particularly on children, need to be undertaken. Behavioral therapy could be provided to overcome trauma.

More details on the evaluation of UNICEF’s UCT program for Yolanda victims are to be discussed during the PSAI Annual Conference this coming August 31, 2016 to September 2, 2016 in Naga City.

The PSAI hopes that stakeholders of disaster risk management and social protection will join the community of statisticians in this upcoming conference. Disasters keep recurring, and it is time we, especially our nation’s new government, learn from lessons on how best to help those in need of help the most. – Rappler.com

Dr. Jose Ramon “Toots” Albert is a professional statistician who holds a PhD in Statistics from the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He is a Senior Research Fellow of the government’s think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), and the immediate past president of the country’s professional society of data producers, users and analysts, the Philippine Statistical Association, Inc. for 2014-2015.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.