SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

One of the President’s most important powers is to direct and control the national agenda for development. And for its first 100 days, the Duterte administration chose to highlight the country’s drug problem and implemented a drug war to address it.

One major justification for this policy is the extent of drug use in the country, which is thought to worsen criminality and corruption. Estimates vary, but for our purposes let’s say that the drug problem affects somewhere between 1.8 to 4 million Filipinos.

Aside from drugs, however, a great many other social problems affect even more millions of Filipinos. Therefore, following the government’s logic, we ought to be waging similarly intense “wars” – or focused campaigns or programs – on these other issues as well.

Below is a short list of 5 other development “wars” the country ought to be waging, given the sheer number of Filipinos they affect. We also included possible strategies for each of these wars. Hopefully, these will enjoy as much attention from our President beyond his first 100 days.

1) War on poverty

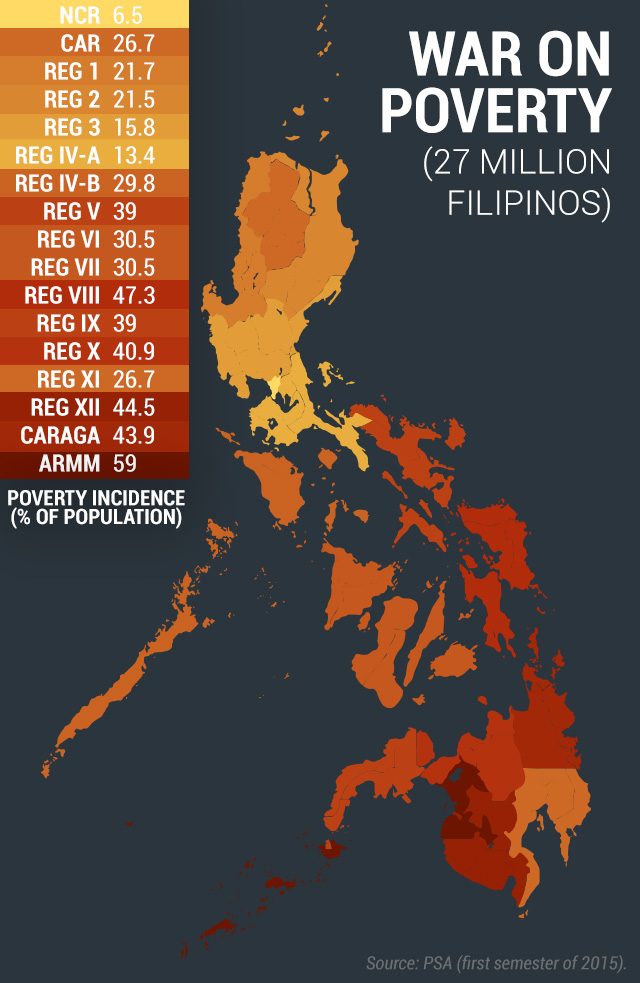

How bad the problem is: For several decades the country has had a chronic poverty problem. Despite high economic growth rates in recent years, the poverty rate has remained stubbornly high and even increased in recent years, translating to even more poor Filipinos than before. The poverty problem is particularly acute in Mindanao, as shown in Figure 1: whereas only 6.5% of people in NCR are poor, on average around 40% of people are poor across Mindanao’s regions.

What to do about it: Poverty is a devilishly complex issue that requires solutions in both the short run and long run. In the short run, poverty can be alleviated by making sure that inflation is tempered (e.g., food prices remain low) and people find jobs and stay in them. In the long run, the transmission of poverty across generations can be stopped when the poor are able to invest in their children’s education and health (as made possible by programs like conditional cash transfers).

2) War for water and electricity (16-17 million Filipinos)

How bad the problem is: Poverty is difficult to escape without access to basic amenities like water and electricity. As of 2014, around 14.5% of all households (or 16.5 million Filipinos) have no access to safe water supplies, and instead rely on unprotected sources like wells, springs, rivers, ponds, lakes, and rain water. Meanwhile, as many as 6.7 million Filipinos also don’t have access to sanitary toilet facilities, and 16 million still don’t have access to electricity as of 2013.

What to do about it: The national and local governments can allocate greater budgets for service expansion of water distribution, sanitation, and electrification. But where investments and tax revenues are inadequate, these efforts can be supplemented by funds coming from development aid agencies and the private sector through public-private partnerships. Too few of such partnerships exist today, and driving away aid money certainly doesn’t help in this cause.

3) War on hunger and undernourishment (14-17 million Filipinos)

How bad the problem is: Growth is meaningless if so many people remain to be hungry. According to the Social Weather Stations nearly 3.4 million Filipino families (or 17 million Filipinos) suffered from involuntary hunger as of June 2016. This is despite the general decline of hunger incidence among families since 2010 (Figure 2). Meanwhile, the PSA estimated that there are as many as 13.6 million undernourished Filipinos as of 2015.

What to do about it: Hunger refers to inadequate quantities of food, while malnutrition refers to their inadequate quality. Hence, solving both issues is not as simple as buying more food and giving them to the poor for free or at a discount. Also, contrary to conventional wisdom, large-scale solutions like feeding programs may also be less effective than small-scale solutions, such as the simple provision of iodized salt to address iodine deficiency.

4) War on underemployment (7 million Filipinos)

How bad the problem is: As of October 2015 around 2.4 million Filipinos in the labor force didn’t have work. But a more serious problem than joblessness is underemployment, where one has a job but still needs or wants more work. This affected around 7 million Filipinos as of October last year. All in all, the country needs to generate nearly 10 million jobs to solve both unemployment and underemployment.

What to do about it: The country needs to improve not just the quantity of jobs out there, but also their quality. First, jobs have to be created by attracting more investments into the country, promoting entrepreneurship, and helping small and medium enterprises. Second, jobs need to be more compatible with the skills and education of people in the labor force. A better match between skills and jobs will also obviate any need for people to seek employment abroad and become OFWs.

5) War for education (4 million Filipinos)

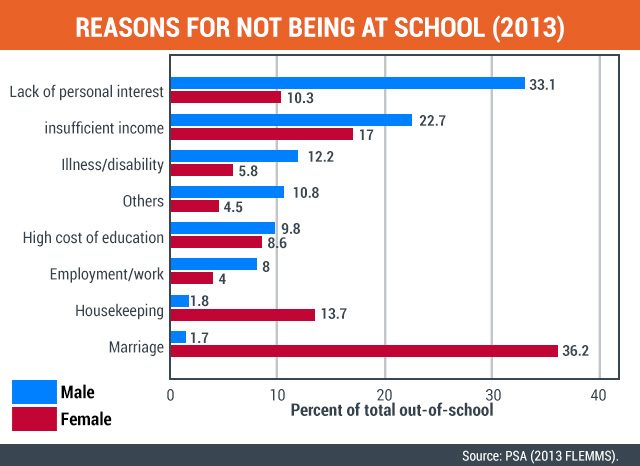

How bad the problem is: Although a vast majority of Filipinos can read and write, a sizeable number still receive inadequate education and drop out of school early. As of 2013, around one in 10 Filipinos aged 6-24 (or 4 million children and teens) were out-of-school. Studies also show that boys drop out because of lack of interest and insufficient family incomes, while females drop out primarily because of marriage and housekeeping duties.

What to do about it: School attendance and retention can be addressed from both demand and supply sides. On the demand side, policies need to address the economic reasons that prevent school entry and retention. Here small financial incentives work well, justifying the expansion of programs like 4Ps. On the supply side, the government must continuously expand school resources and reduce school-related costs, especially with the onset of senior high school.

Conclusion: Development is a battle on many fronts

Needless to say, the above list of other wars is hardly exhaustive. We haven’t included problems that affect the more than 100 million Filipinos, such as public and private corruption, inadequate health insurance coverage, the prevalence of political dynasties, and risks from climate change.

We also haven’t mentioned issues which affect relatively few Filipinos but are nonetheless important, such as infant and maternal mortality, urban traffic congestion, homelessness, and gender discrimination.

To be sure, the country does have a serious drug problem, and it is understandable that many Filipinos think of the drug war as urgent and necessary, given past administrations’ perceived inaction on the matter.

However, a country’s development can be thought of as a battle on many fronts. Hence, it cannot be won by directing all our energies on any single front alone.

Now that we’ve heard the policy direction “from above”, perhaps it’s time for us to initiate the policy process “from below” – for the people to articulate the policies they would like the Duterte government to act on. Policymaking can take years to complete, so now would be the best time for Filipinos to speak out on the issues that matter to us the most. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD student and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to Kevin Mandrilla for helpful comments and suggestions.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.