SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Like a disease, poverty requires cure and prevention](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/4883319AD5ED4011A59A09435C782254/tl-vulnerability.jpg)

The eradication of poverty continues to be at the heart of the development agenda. The Philippines, together with 192 other countries, committed to attaining the Sustaining Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, which includes a goal to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere.”

To systematically adress the problem, it is crucial to count how many people are in poverty, to examine why people are poor, and to develop interventions for empowering poor people to have a fighting chance of getting out of poverty in a more sustainable manner.

While the government and various poverty stakeholders provide interventions to assist the poor, these programs are often directed at those who have been identified as poor, and may not necessarily include those at risk of becoming poor.

The scope of assessments and interventions must take into account the dynamics in poverty.

Some of the poor may exit poverty (from time to time, or even sustainably) and some of the non-poor can also slide into poverty, especially in the face of events such as sharp rises in prices, natural disasters, job losses, health problems or death of a family’s main income earner.

Addressing risk of future poverty

It is important to craft a roadmap where strategic interventions are based on a careful examination and reexamination of data not only on poverty, but also on vulnerability, which essentially pertains to the risk of future poverty.

Poverty rates across the Philippines have been unchanged in the period 2003 to 2015, especially from 2003 to 2012, despite the robust economic growth in the last decade.

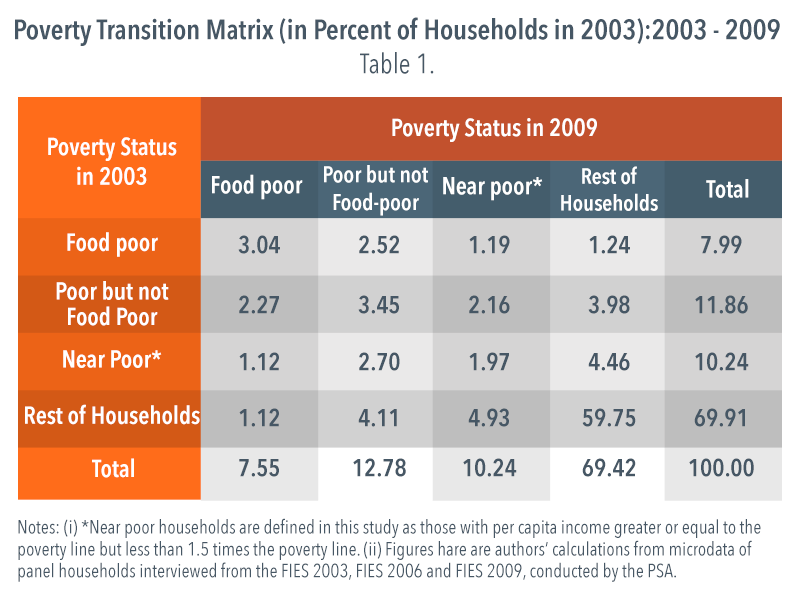

While gross poverty rates have been practically at a standstill, data on the poverty status of “panel” households interviewed in the 2003 Family Income Expenditure Survey (FIES) that were further interviewed in 2006 and in 2009 suggests that some poor households in 2003 have exited poverty in 2009, and some non-poor households in 2003 have fallen into poverty by 2009 (see Table 1 below).

Among near-poor households (that are not poor but with incomes less than 1.5 times the poverty threshold) in 2003, three out of 10 fell into poverty in 2009.

Thus, the near-poor are more vulnerable to income poverty than the non-poor.

Curative, preventive methods

Like a disease, poverty carries a stigma, and also requires interventions given its harm.

Approaches to poverty can be either curative (i.e., alleviating the conditions of the poor, and/or helping them exit out of poverty, just like treating the sick), or preventive (i.e., protecting those vulnerable from the risks and harmful effects of poverty by building the resilience of the vulnerable, just like treating those at risk of getting sick).

The National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC), established to serve as the coordinating and advisory body for the implementation of the social reform and poverty alleviation agenda, espouses a comprehensive, universal, and transformative social policy, including a rights-based approach, to ensure that reaching zero (poverty) becomes the cornerstone of the country’s development policies.

The NAPC also takes cognizance of poverty’s many faces, including vulnerabilities stemming from risks to welfare such as uncertainties from lack of decent work and educational attainment of household members, insecurity from land tenure and lack of productive assets, imperfect and asymmetric information on opportunities, as well as food insecurity, uncertain access to public goods, and asset damages from disasters and violence.

In the Philippines, social protection programs of the government such as Pantawid and SocPen, implemented by the Department of Social Welfare and Development, were communicated as poverty reduction programs.

But they are actually meant more to build resilience of the poor, especially as cash transfers are meager and are not going to change their poverty status.

Nonetheless, cash transfers (including the government transfers to cushion the impact of tax reforms) reduce the poverty gaps (i.e., the difference between the poverty thresholds and the poor’s income) of the 4.4 million Pantawid beneficiaries and the indigent elderly among the 3 million SocPen beneficiaries.

Government needs to strengthen social protection to progressively include those vulnerable and implement specific programs that take account of varying circumstances of households that are poor or vulnerable to poverty.

Protecting the vulnerable

Following previous work that use a “modified probit model” on per capita income data to predict the probability that a household will be poor in the future, vulnerability estimation was carried out using data sourced from the FIES for the years 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, and 2015. Used in this were a number of household characteristics, including employment, education, location, dwelling characteristics, experience in price surges, and experience of severe storms.

Based on the resulting estimates of the probability of a household being poor in the future, households are classified as vulnerable if they their chance of being poor in the future exceeds the national poverty rate, and as nonvulnerable otherwise.

The vulnerable are categorized into highly vulnerable if the probability of being poor is greater than 50% and relatively vulnerable if the probability is between the national poverty rate and 50%.

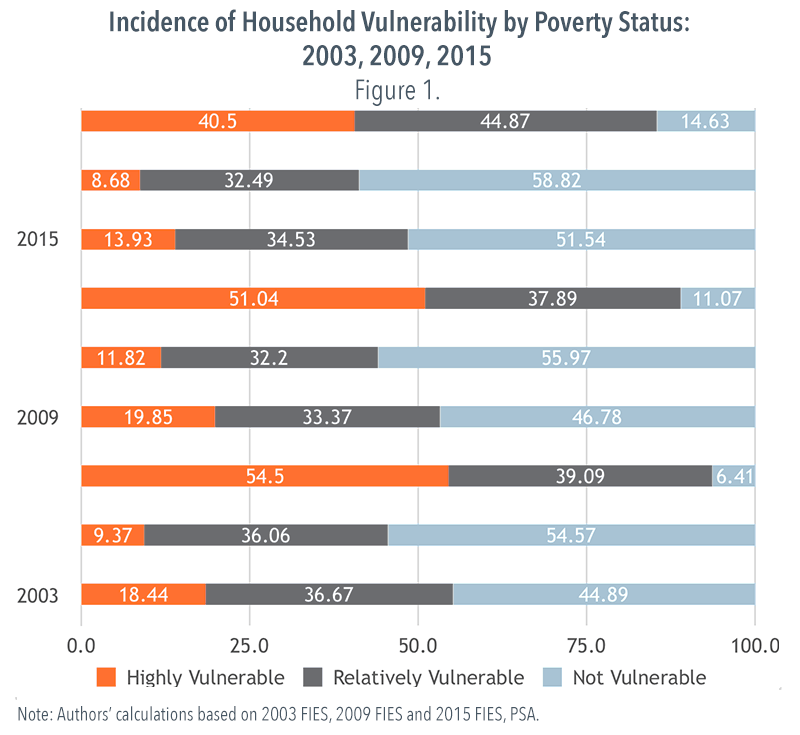

The proportion of households that are vulnerable across the population for the years 2003, 2009, and 2015 by poverty status is shown in Figure 1 below.

Across the years, the proportion of households in the Philippines that are vulnerable to income poverty has been around double to triple the corresponding official estimates of the proportion of households in poverty.

Household vulnerability rates have been steadily declining from 55.1% in 2003 to 48.5% in 2015.

Among poor households, the proportion that are found to be highly vulnerable to income poverty has also decreased from 54.5% in 2003 to 40.5% in 2015 (Figure 1).

The overall percentage of households that are relatively vulnerable has also decreased but at substantially lesser rates from 36.7% in 2003 to 34.5% in 2015, on account of the increase in the proportion of poor households that are relatively vulnerable, which offset the decline in the proportion of non-poor households that are relatively vulnerable.

As of 2015, about three-fifths (58.8%) of non-poor households are classified as not vulnerable to poverty, but the bulk of vulnerable households continue to be non-poor households with non-poor households having 71.0% share of all vulnerable households.

In 2015, about one-seventh (13.9%) of households throughout the country were highly vulnerable and about a third (34.9%) were relatively vulnerable.

Thus, as of 2015, about half (48.5%) of Filipino households were vulnerable to income poverty, a third of which were highly vulnerable.

Rural vs urban

The rural population is more vulnerable than its urban counterpart, with vulnerability rates at two thirds (69.3%) of all households at in rural areas, compared to two-fifths (40.4%) of urban households, as of 2015.

Although vulnerability is a largely rural phenomenon, the proportion of highly vulnerable households in rural areas has declined by 7.1 percentage points from 27.6%in 2003 to 20.5% in 2015.

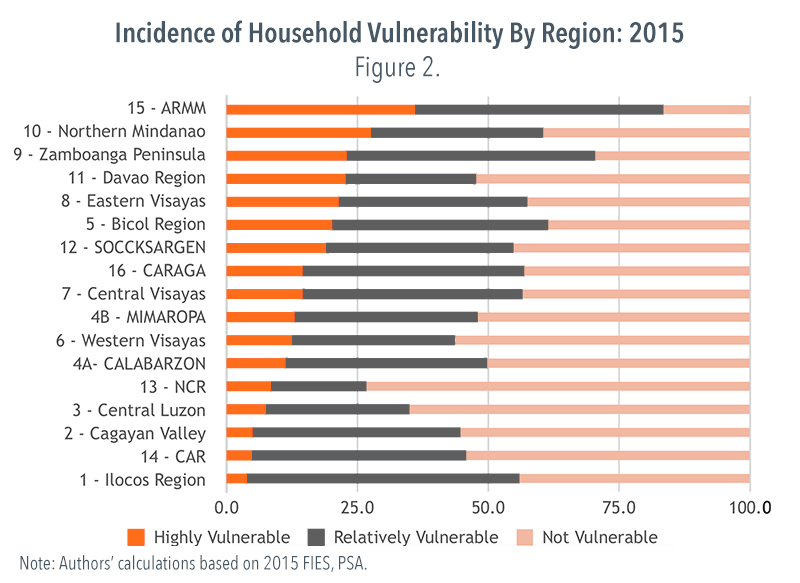

Across the regions, ARMM is the most vulnerable region (83.3%) – more than two fifths of these are highly vulnerable (see Figure 2).

The Ilocos Region has the lowest proportion of households (3.8%) that are highly vulnerable among the regions, but as much as 52.0% of its households are relatively vulnerable, putting it in the middle among regions as far as vulnerability rate is concerned.

The NCR (26.6%) and Central Luzon (34.9%) are the only regions with (overall) vulnerability rates below 35%.

Most vulnerable: Fishermen, farmers, children

Republic Act 8425 or the Social Reform and Poverty Alleviation Act provides the government’s framework for social protection and defining poverty.

This law also identified 14 basic sectors, that require focused intervention for poverty alleviation.

These sectors are: (1) Farmer-peasant; (2) Artisanal fisherfolk; (3) Workers in the formal sector and migrant workers; (4) Workers in the informal sector (5) Indigenous peoples and cultural communities; (6) Women; (7) Differently-abled persons; (8) Senior citizens; (9) Victims of calamities and disasters; (10_ Youth and students; (11) Children; (12) Urban poor; (13) Cooperatives; and (14) Non-government organizations. The PSA has obtained estimates of poverty for 9 of the 14 basic sectors making use of merged Labor Force Survey (LFS)-FIES data.

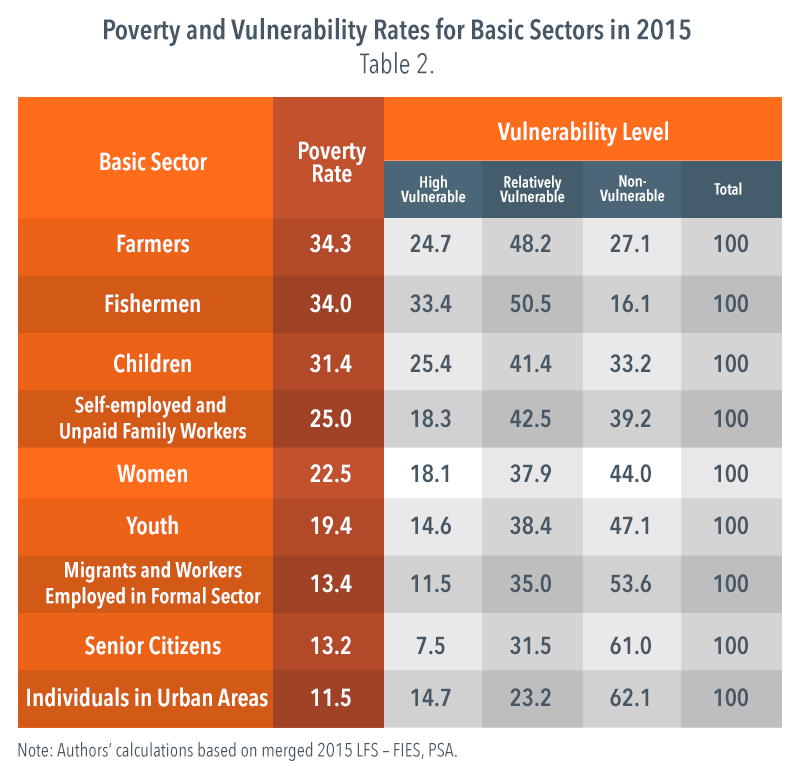

The share of the basic sectors that are highly vulnerable, relatively vulnerable and non-vulnerable to income poverty, also based on merged results of the LFS-FIES, can likewise be generated (see Table 2).

We can observe that vulnerability rates for the populations of the basic sectors are much larger than corresponding shares of the population in poverty.

The vulnerability rates, and the proportions of the basic sectors that are highly vulnerable, are consistently highest for fishermen, farmers and children.

Consistent also with patterns in poverty rates, the lowest vulnerability rates are also observed for persons residing in urban areas, and for senior citizens.

Ways forward in tackling poverty

While the country has had some progress in reducing poverty from 1990, the rate has been rather minimal in recent years, with a substantial proportion (16.5%) of households remaining poor as of 2015 and about 3 times as many (48.5%) vulnerable to poverty.

To overcome obstacles in reducing poverty, government and all poverty stakeholders need to see the importance of forward-looking planning and risk resilience building in a context of uncertainty.

Poverty alleviation and social protection efforts have typically resolved around the formulation and implementation of “one size fits all” strategies.

For instance, social protection actions involve the provision of a uniform cash assistance to all beneficiaries, rather than accounting for differentiated needs. SocPen, for instance, provides P500 monthly pensions for all beneficiaries, who are by law, supposed to be indigent senior citizens.

Pantawid provides P300 monthly education grants for pre-primary and primary students, P500 monthly education assistance for high school students and Php500 monthly health grants to households, without recognizing differences in opportunity costs for schooling between boys and girls.

Support from the development community during extreme crises, such as unconditional cash transfers (UCT) of monthly USD100 assistance provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to 10,000 poor households in the aftermath of the effects of super typhoon Yolanda have themselves been one size fits all, in both the assistance and the payment modes.

The TRAIN law also provides cash support of P200 per month for this year (and P300 monthly in 2019 and 2020) for 10 Million lower income beneficiaries, including the over 4 million Pantawid beneficiaries, and 3 Million SocPen elderly beneficiaries.

To get more impact in efforts to reduce poverty, government needs to build an enabling environment for shared action and responsibility with local governments and other stakeholders.

We also need to formulate an action agenda that addresses all relevant risks to vulnerability jointly seeing synergies, tradeoffs and priorities in policy responses, using all available resources, institutions and means of implementation across different contexts.

We not only have to “cure” poverty, but also “prevent” it, or at least mitigate its harm to people who are likely going to suffer from this disease.

An examination of data on both poverty and vulnerability will not only allow vulnerable households to reduce the effects of adverse events (such as natural calamities, price shocks, and idiosyncratic shocks) on their conditions but also empower them to seize the moment and take advantage of opportunities for improving their prospects for a better future today. – Rappler.com

(Editor’s note: This Rappler article is a condensed version of a Discussion Paper released at the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS.

Dr. Jose Ramon “Toots” Albert is a professional statistician and policy researcher. He is a Senior Research Fellow of the PIDS, the government’s think tank, and a past president of the country’s professional society of data producers, users and analysts, the Philippine Statistical Association, Inc. From 2012 to 2014, he was seconded by PIDS to the defunct National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) as the NSCB Secretary General. He teaches part-time at the De La Salle University College of Business and at the Asian Institute of Management.

Jana Flor V. Vizmanos is a Research Analyst at PIDS. She earned her degree in BS Economics at the University of the Philippines Diliman in 2014 where she graduated cum laude.)

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.