SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Is the Philippine economy overheating?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/CA15D1B23EEF4F05B7E9B171C4D0E288/img/73EA71E747D14610BC735D974BAE8763/PH-economy-overheating-Sept-28-2018.jpg)

A number of economists here and abroad have warned that the Philippine economy might already be “overheating.”

For example, the IMF (International Monetary Fund), the World Bank, the AMRO (ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office), and Fitch have all cautioned us against “early signs” and “increasing risks” of economic overheating.

Meanwhile, President Duterte’s economic managers – along with HSBC, Moody’s, and Capital Economics – have minimized or downplayed such prognosis.

Is the Philippine economy really overheating? How can we know that?

What is overheating?

When a car engine or electric circuit overheats, it usually means there’s an unusual or unexpected buildup of heat in the system, thus raising its temperature.

Economic overheating is analogous to this. When an economy overheats, it means there are more goods and services produced in an economy than expected. This is typically in response to greater demand from consumers and producers, and manifested by rising inflation or accelerating prices.

But how can an economy produce more goods and services than expected? Here we need to distinguish between actual GDP and potential GDP.

Actual GDP (gross domestic product) measures the value of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a given period of time.

Potential GDP, meanwhile, is a hypothetical concept that answers the following question: how much output can the Philippine economy produce if all Filipino workers, their machines and equipment, were fully utilized?

Sometimes, actual GDP and potential GDP are on par. But an imbalance – especially a prolonged one – doesn’t bode too well for the economy.

If actual GDP is larger than potential, then there’s overheating. The economy churns out goods and services beyond its capacity, and prices and wages tend to rise.

But if actual GDP is lower than potential, production slackens and more workers and machines become out of work. Prices and wages also tend to decline.

So is the economy overheating?

How do we know if the Philippine economy is overheating? Let’s look at some indicators.

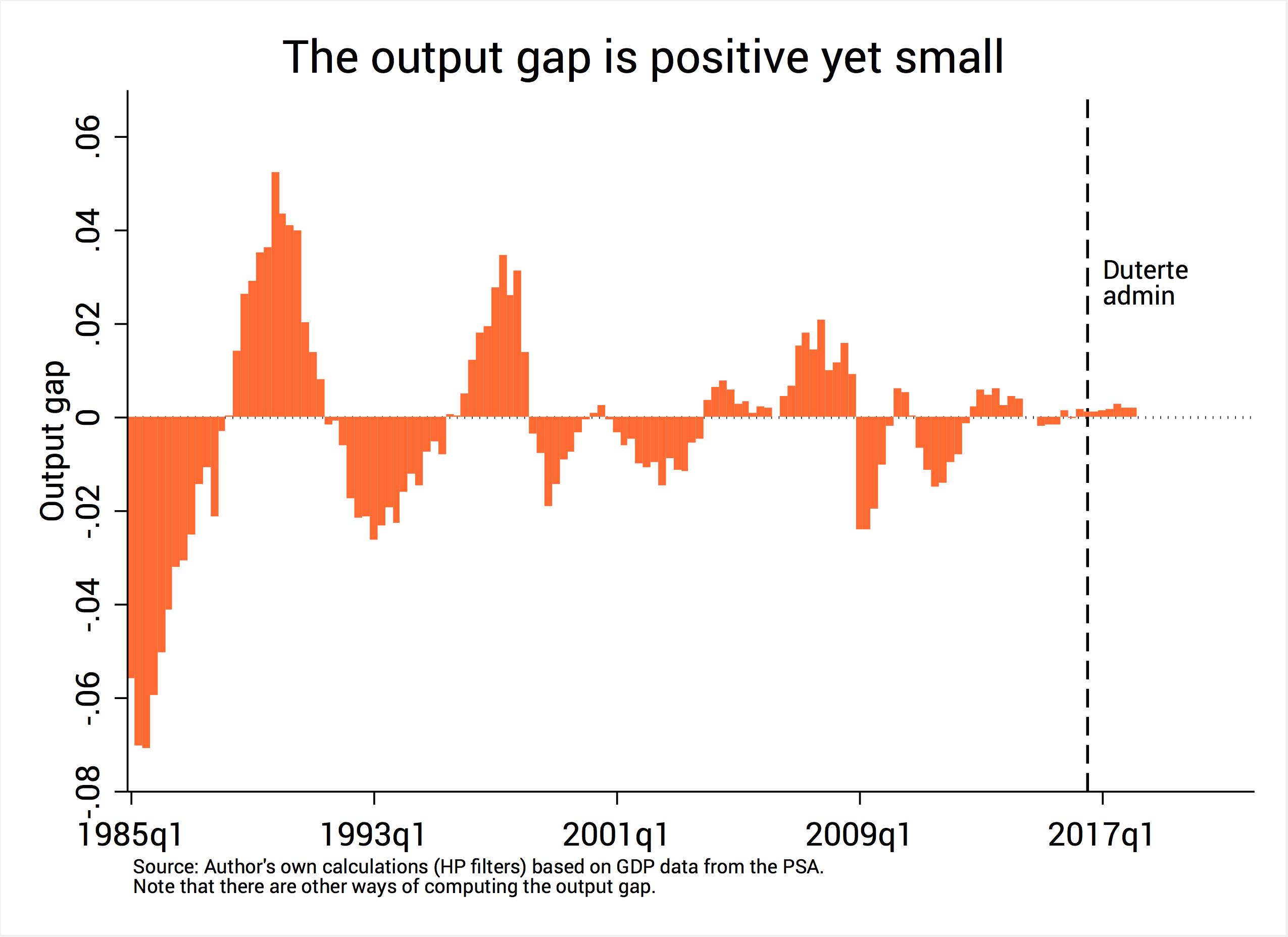

First, the difference between actual GDP and potential GDP – otherwise known as the “output gap” – is shown in Figure 1.

Notice that in recent times, from 2016 to present, the output gap is positive yet small compared to past levels. This suggests there’s overheating, albeit minimal.

Also notice that we’re now experiencing the 8th consecutive quarter of a positive output gap. The last time this happened was in 2007 to 2008, in the run-up to the global financial crisis.

Figure 1.

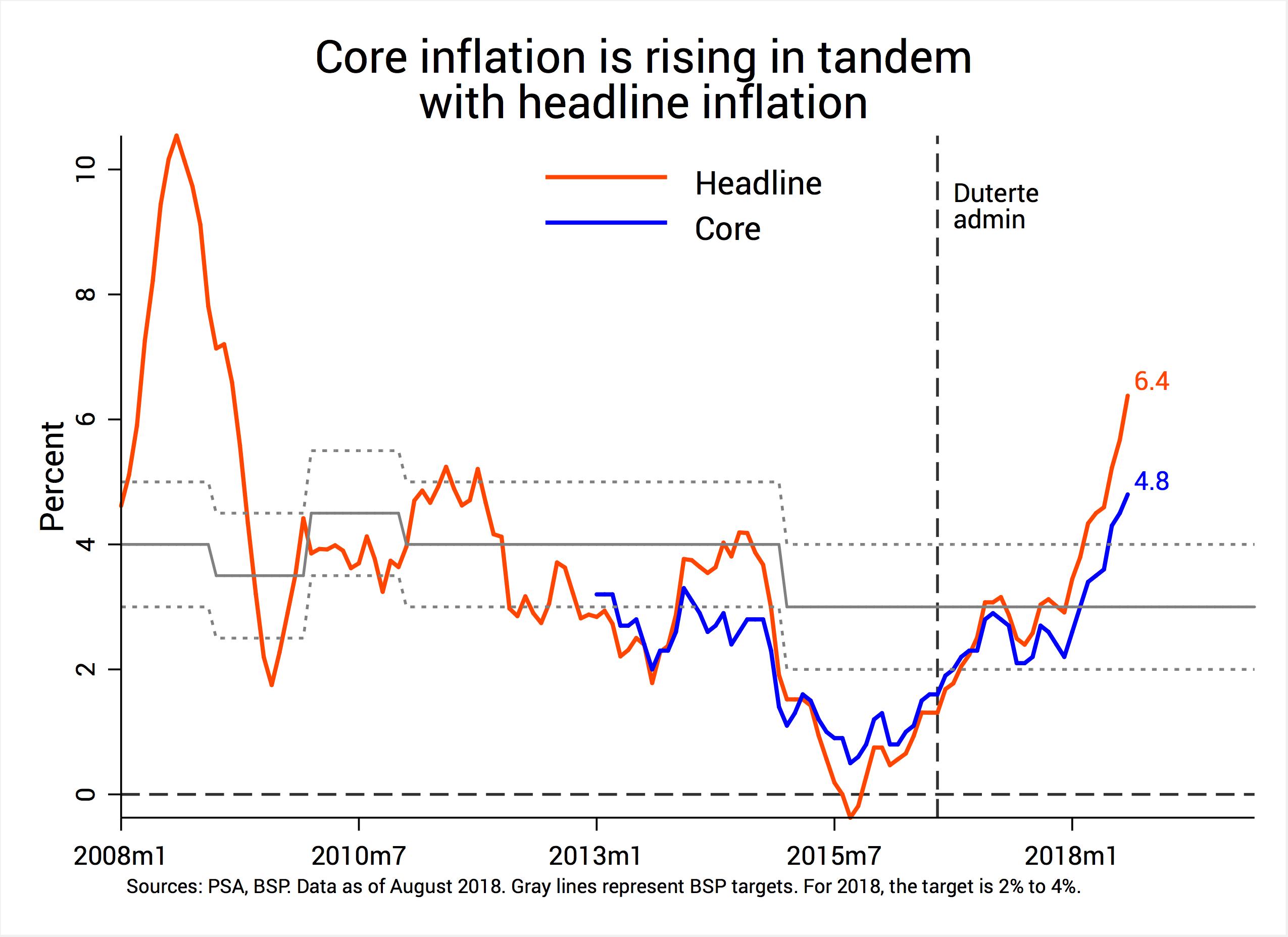

Second, inflation – which measures how fast prices are rising – is currently at its highest in 9.4 years, as shown in Figure 2.

Although alarmingly high, some say this level of inflation is no proof of overheating because it’s driven primarily by increasing costs of production – say, higher world oil prices and the rice crisis – rather than by stronger demand.

However, the data belie this.

The blue trend in Figure 2 shows the inflation rate if we remove commodities which typically have volatile price movements, such as rice, corn, meat, fish, vegetables, and petroleum products.

Notice that this blue trend (“core” inflation) is rising in tandem with the orange trend (“headline” inflation) in recent months.

This, to me, is stronger evidence of overheating.

Higher world oil price and the rice crisis, despite their predominance in the news, can only explain part of rising inflation. Instead, it might be borne in larger part by unmoored inflation expectations. (READ: Why is Philippine inflation now the highest in ASEAN?)

Figure 2.

Third, we can also look at credit growth.

When people take on more loans – either for their businesses or for their own personal consumption (car loans, housing loans, etc) – it could signal brisk economic activity.

Figure 3 shows that in 2016 there was a sharp rise in total loans from universal and commercial banks. This could have triggered early red flags about overheating. Overall credit growth fell in 2017, but rose again early this year.

Figure 3.

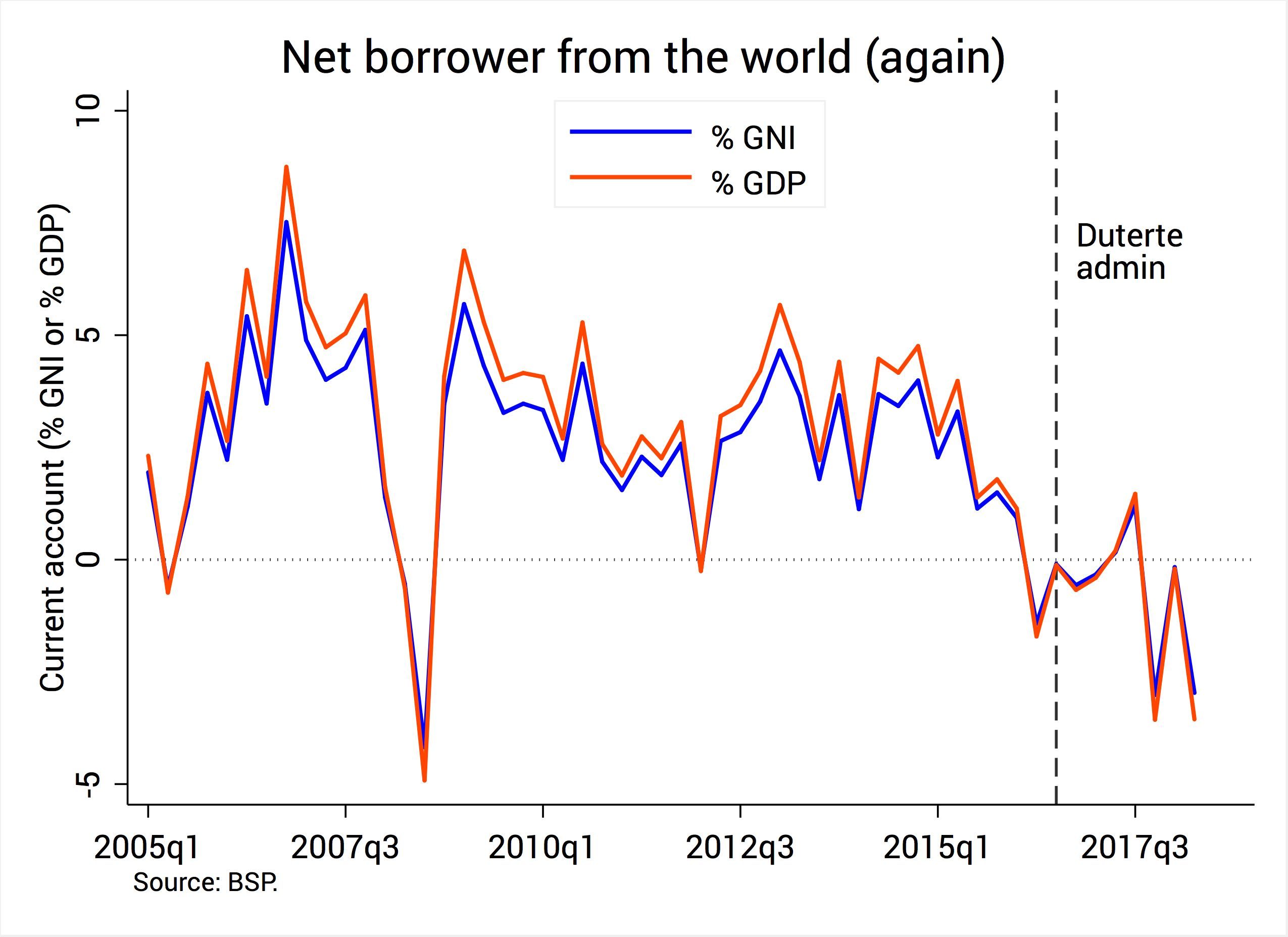

Fourth, we can look at the country’s “current account deficit.”

Figure 4 shows that it is widening. (READ: Duterte’s ‘twin deficits’: What you need to know)

This is important because the current account reflects the gap between local saving and investment. If the current account deficit is widening, this suggests we’re not saving enough and we’re financing our investments by borrowing from the rest of the world.

Figure 4.

A growing current account deficit is not necessarily bad. It could mean, say, that the Duterte administration’s infrastructure program (called Build, Build, Build) is well on its way, and that we’re actually planting the seeds for future growth and prosperity.

However, this boost in future growth could also mean we’re planting the seeds for higher inflation in the future.

What can government do?

Combining all of the above – a positive but small output gap, rising core inflation, swelling credit growth, and a widening current account deficit – the Philippine economy does seem to be overheating, although the jury is still out as to its magnitude.

What can government do in response?

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) plays a key role here.

To cool down an overheating economy, the BSP could douse it by imposing higher interest rates. This policy works by dissuading people from taking on more loans – whether for production or consumption – thereby tempering credit growth and future economic activity.

This is what exactly the BSP has been doing in the past months. After interest rate hikes in May and June (0.25 percentage point each) and in August (0.50 percentage point), the BSP did the same on Thursday, September 27 (another 0.50 percentage point).

But large and frequent interest rate hikes – though necessary now – could also dampen economic growth in the future.

Indeed, Figure 1 shows that episodes of overheating are typically followed by periods of slacking production. This is no coincidence: inflation borne by overheating prods the central bank to take drastic steps that could later bring the economy to its knees.

This is why we need to detect and forestall economic overheating as early as possible. The longer we wait, the more painful the economic blowback we’ll have to suffer later on.

Heed the warnings

Although BSP officials have reassured the public that they’re closely monitoring the situation and standing ready to act, other economic managers remain stubbornly impervious to the warning signs about overheating.

Finance Secretary Sonny Dominguez, for example, recently said that, “We believe that we’re not really in danger of overheating at the moment. We still have a long way to go.”

But to fix an overheating car, you don’t just continue driving it on the highway. Instead, you pull over, open the hood, and let things simmer down.

In like manner, the economic managers cannot just turn a blind eye to the blinking red lights and blindly push through with their pet projects, especially since some (like Build, Build, Build) could only stoke further overheating.

They must soon heed the warnings and cool down the country’s economic engine before things get way worse. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to Ma. Christina Epetia (UP School of Economics) for helpful comments and suggestions. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.