SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Whatever happened to the Reproductive Health Law?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/4F00CF5FEC4B48388CC4FFAD5A1321DC/img/27348133C6F946A7881C48F6A29BF29B/Whatever-happened-to-the-Reproductive-Health-Law-October-18-2018.jpg)

This week, a new book by Marilen Dañguilan will be launched entitled The RH Bill Story: Contentions and Compromises. It’s all about the history of the Reproductive Health Bill, detailing its historic but tortuous 11-year journey through the legislative mill.

I’ve had a chance to preview the book, and I must say that advocates, researchers, and anyone with even a casual interest on the matter will find no reference that’s more comprehensive or authoritative.

But this got me thinking: Whatever happened to the RH Law since its passage, and what challenges does it face today?

Economics of reproductive health

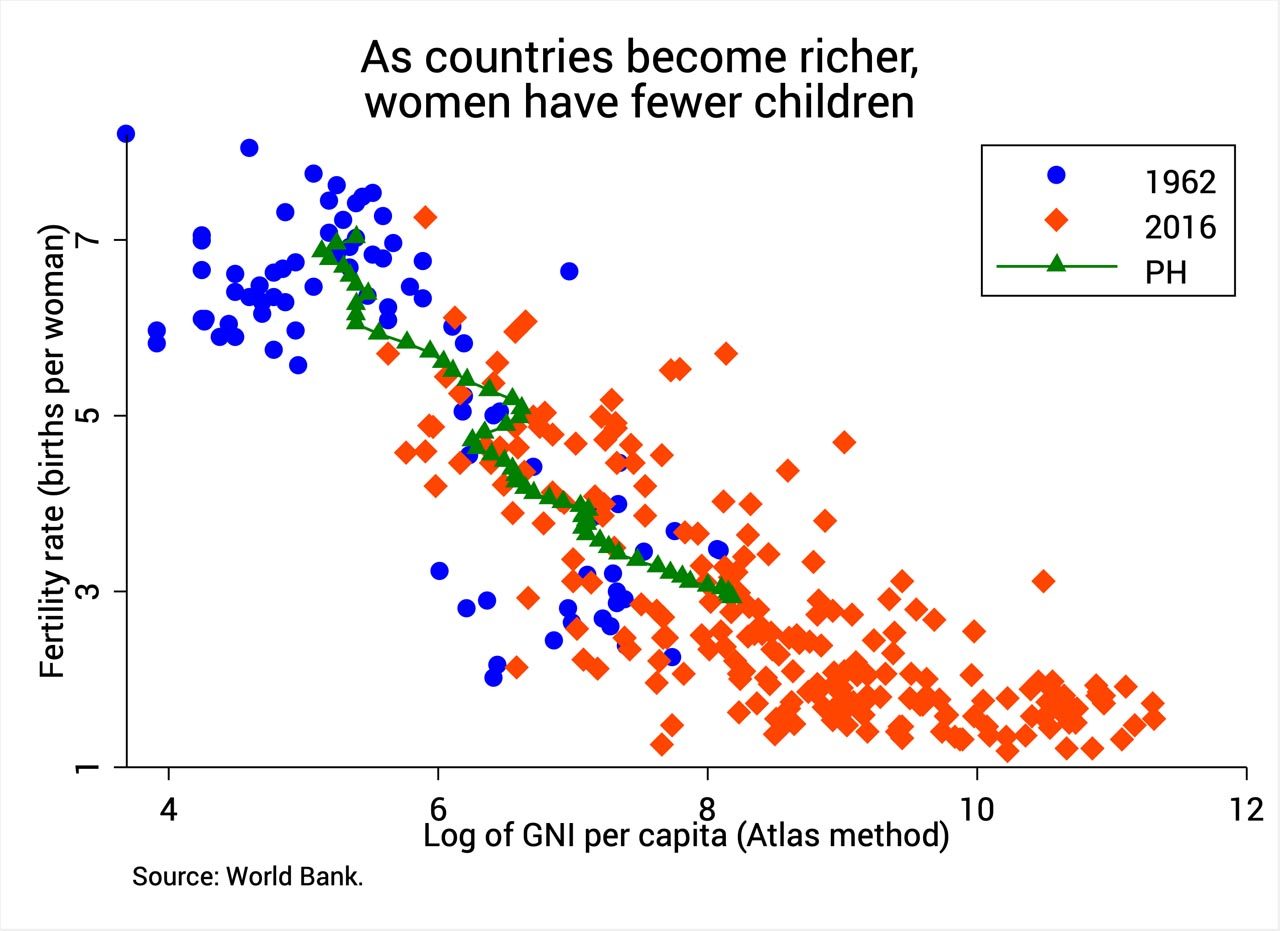

Figure 1 shows a well-established fact worldwide: as countries become richer, females bear fewer and fewer children.

While it was common for our grand-grandparents to have, say, 6 to 7 children, most couples today settle for just 2 to 3 kids.

The reason for this global phenomenon is simple: as women enjoy greater economic opportunities, larger incomes, and empowerment (in a broad sense), rearing children becomes more and more costly – both in terms of money and time.

Figure 1

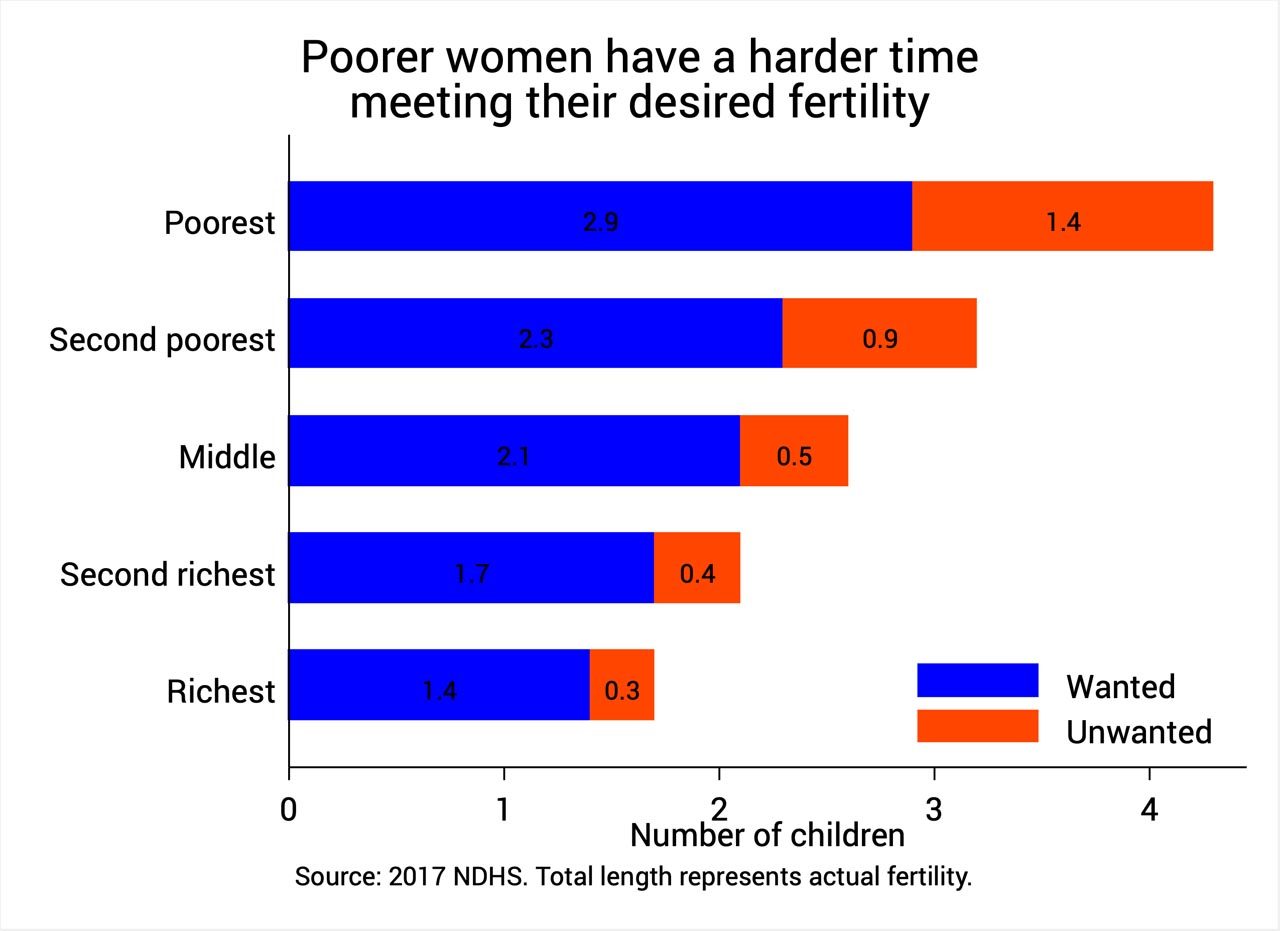

Despite this, many women today still find it difficult to achieve their desired fertility, especially poor women. This much is true in the Philippines, as reported by the 2017 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS).

For instance, latest data show that the poorest fifth of Filipino women not only have the most number of children on average, but they also have the highest level of “unwanted fertility,” or the gap between actual and desired number of children (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

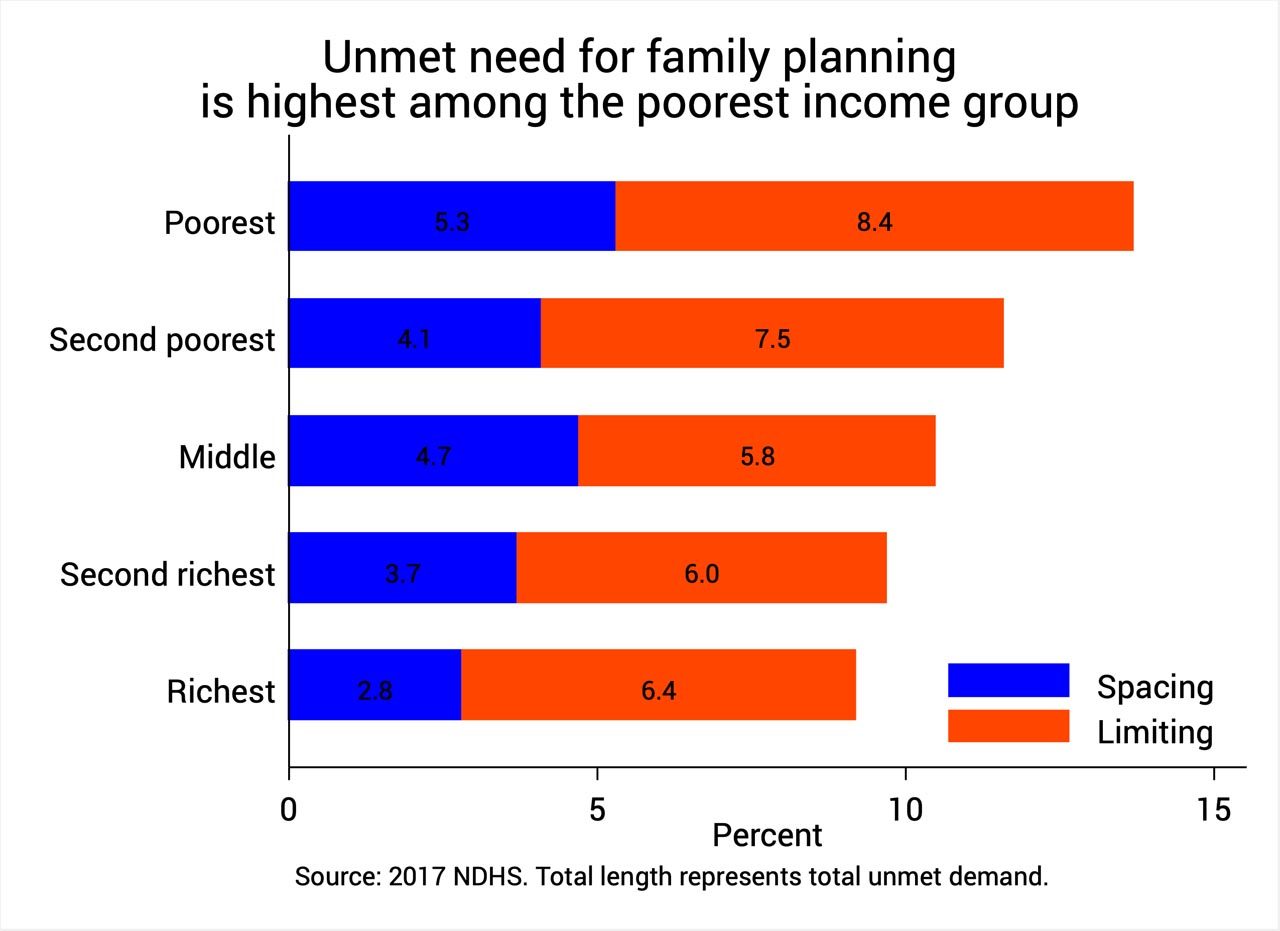

In addition, the percentage of women who want to space or limit childbearing but are not using any contraceptive method – otherwise referred to as “unmet demand” for RH goods and services – is also highest among the poorest (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Why are poor women disadvantaged in terms of fertility choices?

More often than not, it all boils down to lack of access: not only are RH goods and services unaffordable to many poor women, but supplies may also be dearer near where they live. Information about the use and effectiveness of such products also does not reach many of the poor.

This glaring “failure” in the market for RH goods and services provides a rather straightforward, clear-cut case for government to step in and provide corrective subsidies. Hence, the need for measures such as the RH Bill.

Politics of reproductive health

Yet since the very first incarnation of the RH Bill, it turned out to be one of the most contentious and divisive pieces of legislation in our country’s history.

The laborious path toward the RH Law’s passage kept running into the dead-end that is Article II, Sec. 12 of the 1987 Constitution: “The State recognizes the sanctity of life… It shall equally protect the life of the mother and the life of the unborn from conception.”

Because of this provision, otherwise rational debates about family planning or women’s reproductive rights were repeatedly reduced to philosophical, moral, and even existential debates about “life” and “conception.”

On the one hand, artificial family planning methods (like condoms and IUDs) were endlessly demonized as sinful and labeled as abortifacients, even if many scientific studies belie such claims.

On the other hand, “pro-life” groups strongly advocated the use of natural methods (such as abstinence or the calendar method), which some perceived as tedious, impractical, and relatively ineffective.

To begin with, such debates were needless. The spirit of the RH Bill was to allow women to choose freely whichever method of family planning they see fit. They should therefore be presented the full gamut of options, and not restricted to any one type.

Nonetheless, the debates were interminably toxic.

Lawmakers repeatedly found themselves in the middle of a tug-of-war between RH advocates on the one hand and the Catholic Church (among other religious groups) on the other.

The political sway of the Catholic Church, in particular, was in full display during the debates.

Their vehement opposition against the RH Bill manifested, for example, in the way they opposed former president Fidel Ramos and his health secretary Juan Flavier (who advocated the use of artificial methods), and the way they didn’t support calls for the impeachment of former president Gloria Arroyo (who advocated natural methods).

Even academics just had to join the fray to clear up the muddled debates. For example, the usually reticent faculty members of the UP School of Economics took a rare, collective stand on the RH Bill – not just once, but twice (in 2004 and 2008).

Recent roadblocks

But even after the RH Law’s passage in 2012, the end of a long 11-year battle in Congress, disinformation continued to derail its implementation.

No sooner had the RH Law been passed than Catholic groups filed petitions with the Supreme Court to declare it unconstitutional, again invoking the constitutional provision about the State protecting the “life of the unborn from conception.”

This petition prompted the Supreme Court of a status quo ante order that effectively stalled the RH Law’s implementation. It was only in 2014 (more than a year later) that the Supreme Court held that the RH Law was not unconstitutional but for 8 specific provisions.

But Catholic groups did not stop there. Another allied group filed a petition with the Supreme Court that aimed, this time, to stop the government’s purchase, sale, distribution, and administration of artificial contraceptives – as well as their registration or re-certification. They resurrected the old plaint that these products were abortifacients.

This prompted the Supreme Court to impose a temporary restraining order (TRO) specifically on the distribution of Implanon and Implanon NXT (birth control implants), at least until the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) certified that they were not abortifacients.

Tedious proceedings bogged down the RH Law anew, and only in November 2017, two years later, did the FDA finally make the much-awaited certifications.

With the TRO finally lifted, the Department of Health now freely distributes contraceptives to their regional health offices and to various NGOs.

End of the story?

On the one hand, we can breathe a collective sigh of relief now that the RH Law is being implemented without any major roadblock in sight.

On the other hand, Marilen Dañguilan doubts if the story of the RH Law will ever end, what with the demonstrably strong lobby of religious groups (especially the Catholic Church), as well as the legal bedrock on which they can always anchor their counterarguments: Article II, Sec. 12 of the 1987 Constitution.

Yet the RH Law, at its core, is a law about women, their right to choose, and their ability to live better, more meaningful lives.

To this day, it seems baffling to me that men – especially those in the hierarchy of the Catholic Church and the halls of Congress – should have a disproportionately large say on how women should choose for their own bodies and lives.

In 2018, such patronization of women seems positively medieval and out of place. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.