SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Let’s not blame the forecasters for runaway inflation](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/F6CAD6305EEB42588B281AEB78515D65/img/DC4C54CFCA7F402C8AEA36F9B379E0B6/Lets-not-blame-the-forecasters-for-runaway-inflation-Dec-19-2018.jpg)

Lo and behold, some government economists chose to end 2018 by picking a fight with their counterparts in the private sector.

In a surprise – and uncharacteristically combative – move, the Department of Finance (DOF) recently issued a statement where they blamed higher inflation this year on the “faulty” forecasts made by various economists in the private sector.

The DOF’s allegation goes something like this. Inflation can be driven by people’s sheer expectations of future inflation. So when professional forecasters kept predicting higher-than-usual inflation figures this year, this in itself stoked inflation – in the manner of a “self-fulfilling prophecy.”

But worse, the DOF even went on to name 13 different forecasters and ranked them according to how large their forecast errors were.

In this article, I argue that pinning the blame on the forecasters is twisted, unfair, and disappointing. Moreover, it distracts us from the more important issues surrounding inflation.

Blame game

In statistics, the accuracy of a forecast is measured in terms of how far off it is from the actual figure.

For instance, if inflation turns out to be 6% and you forecasted it to be 5.5% only, you underestimated it by half a percentage point (alternatively, you were 8.3% off the mark).

According to the DOF’s analysis – the full text of which has yet to be published – the inflation forecasts of 13 different analysts were off by 6% to 14.9% this year.

But this claim is faulty for several reasons.

First, the DOF used wrong statistical methods and assumptions in assessing the forecasters’ numbers.

For instance, by focusing on margins of error, they used a methodology that’s typically and appropriately used for cross-sectional data but not time-series data. Statisticians would rather look at other statistics like MAE (mean absolute error) or MAPE (mean absolute percentage error).

Second, in the process of chiding private sector economists, the DOF seems to have conveniently overlooked its own errors.

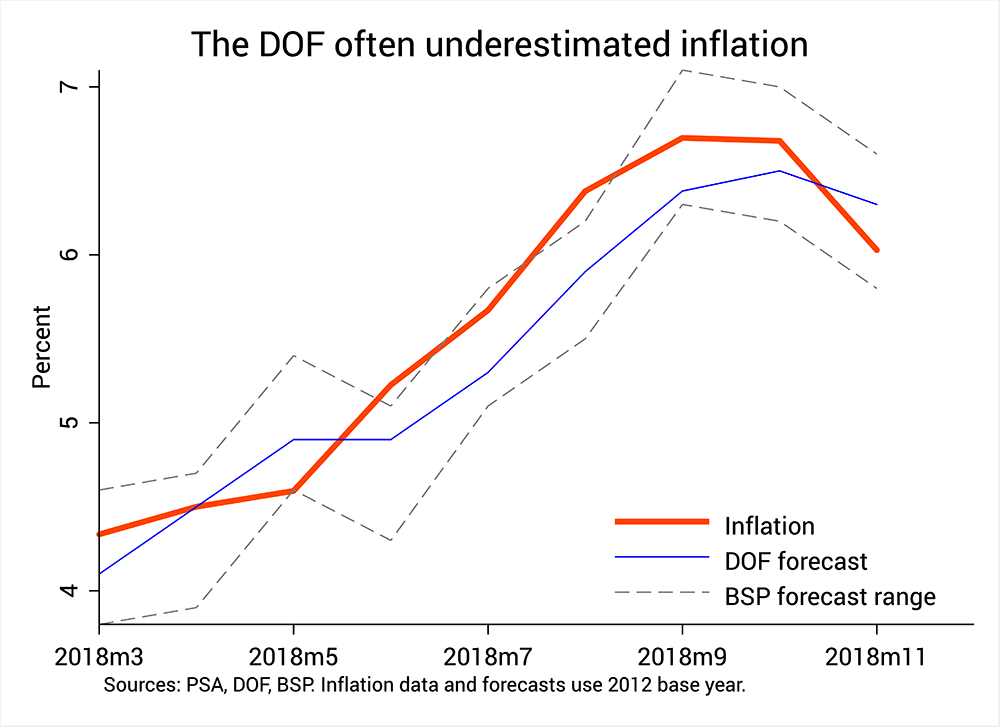

Figure 1 below shows that since March (when the official inflation figures and forecasts started using the new 2012 base year) the DOF often “underestimated” inflation, meaning they forecasted it to be lower than it actually was. (The BSP, by contrast, forecasts a range of values, which is the safer route to take.)

Indeed, if you collect the inflation forecasts published in BusinessWorld this year and compare them with the DOF’s forecasts, you’ll find that the DOF is 3.1 times likelier to underestimate inflation than the average forecaster.

Figure 1.

Overall, 2018 was a challenging year to forecast inflation for any analyst – whether in government or in the private sector.

Calling out analysts – and denouncing them for their errors – is therefore a pointless, malicious, and counterproductive exercise on the part of government.

For want of a clear explanation, Alvin Ang (one of the economists cited by the DOF) surmised that maybe the DOF was just motivated by a “frustration that think tanks can do better forecasts than the government.”

Wrong target

We can quibble no end with the numbers. But the more important point to make is that the figures churned out by forecasters are less important than the DOF might think, and therefore do not deserve this degree of blame.

Sure, there’s reason to believe that people’s expectations of inflation may fuel future inflation.

The reason is that inflation expectations could nudge people into certain behaviors – like hoarding, menu changes, or wage hike petitions – which tend to raise inflation in the future. (READ: Why is Philippine inflation now the highest in ASEAN?)

Yet there’s a whale of a difference between inflation expectations and inflation forecasts. The former is much broader and much more important than the latter, but the DOF seems to be conflating the two.

Economists’ forecasts – like those published in BusinessWorld – do get to influence the expectations of CEOs and other high-level business professionals.

But for tens of millions of other Filipinos – like ordinary consumers, restaurant owners, and hardware store owners – their inflation expectations are shaped by countless other ways, such as the market prices they observe in the palengke or grocery, the reports in the evening news, or the social media posts from their friends and family.

In other words, it’s a stretch to say that the Philippine economy turns on the ups and downs of private sector analysts’ forecasts. Thus, they can hardly be blamed for the spell of high inflation that befell our country this year.

Slippery slope

By playing the blame game, the DOF is also treading perilously close to a slippery slope.

For instance, if we accept for a moment that inflation forecasters do cause a substantial amount of additional inflation to occur, what should be the policy recommendation?

For all inflation forecasting to stop? For media outlets to impose a blanket ban on all forecast-related stories? For the Philippine Statistics Authority to quit publishing inflation figures altogether?

In their press release, the DOF even said, “Researchers are taught early on in college and graduate school. It is an even more crucial lesson when your research is no longer subject to a university’s Institutional Review Board.”

What is the DOF trying to achieve by making such statements? Is it really necessary to say such things?

Antagonistic remarks like these only put at risk otherwise friendly relations between government and the private sector. Already, some analysts have expressed their reluctance to participate in the future inflation expectation surveys regularly conducted by government.

What’s the long game here for the DOF?

Distraction?

Economic forecasting is notoriously difficult. It is – and always will be – riddled by some amount of error.

But this hardly gives government any excuse to blame our economic hardships this year on private sector forecasters.

Rather than point fingers, the DOF might do well to exert its energies instead on policies and programs that will genuinely help improve the plight of our people.

Some think that the DOF is merely distracting us from their own blunders and shortcomings in recent months, most notably the railroading of the TRAIN law and their faulty implementation of it.

We might ask them in return: How come the DOF grossly underestimated the impact of TRAIN on inflation? Why won’t they publicly release the actual data and models they used to estimate the various impacts of TRAIN?

Moreover, why are they pushing for the sequel of TRAIN (called the TRABAHO Bill) even without first thoroughly evaluating and auditing TRAIN’s impact on the Filipino people’s incomes and welfare?

Before casting stones at the forecasters, some DOF officials will do well to consider first if they are without sin. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.