SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I recall how I reacted to this image with a combination of bemusement and cynicism. For it struck me there and then that the promise of globalization was a delicious lie. The farmer from America could perhaps afford to fly to India to have a cup of tea with some Indian agriculturalists, but it would be a long time before an Indian farmer could afford to fly to Texas to share some tacos with his American counterparts. And even if he could afford it, he probably would have been denied a tourist visa, on the grounds that he may have been an economic migrant.

That’s the reality of capital-driven globalization, and it sucks.

It ain’t new, this Globalization Thingy.

As a lecturer of Southeast Asian politics and history I constantly find myself warning my students not to use trendy terms. Among the terms I loathe the most is “globalization” because it is such a prissy, self-conscious, oh-am-I-not-too-sexy-for-my-shirt sort of term. The word has been bandied about so much by now that it is old hat, and yet for so many people it sells itself as something novel and exciting, when in fact it is not.

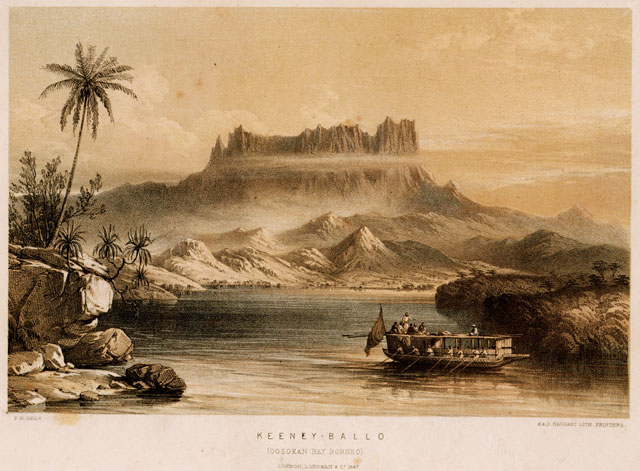

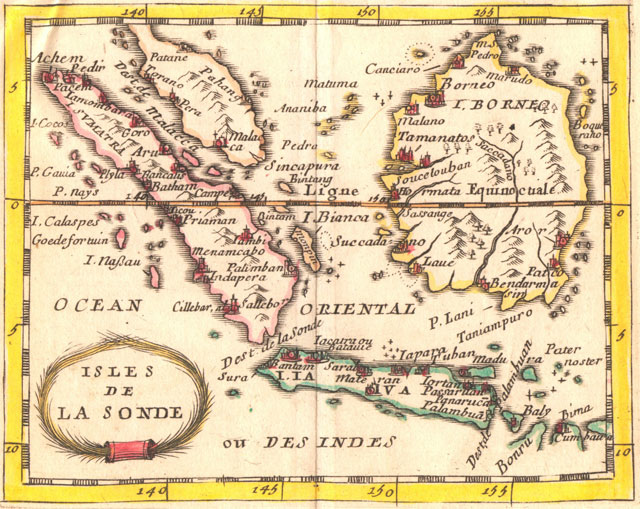

When people talk about globalization in Southeast Asia today, they seem to have conveniently forgotten the facts of 2,000 years of recorded history. We talk about globalization as if it is only now – today – that we realize that we live in a crowded Southeast Asia with neighbors all around us.

But this impression merely underscores the fact that our consciousness, epistemologies and vocabularies have been so deeply marked and shaped by the colonial encounter and the regime of the political border. It is only because we – the ASEAN citizens of the postcolonial era – have no tactile memory of the precolonial past of our region that we think that being able to hop on a plane from Manila to Singapore, to Kuala Lumpur, to Jakarta, to Bali is such a funky experience.

Well, let the historians remind you that centuries ago our ancestors were a million times funkier than we are today, as they lived in a world without passports. (Yes, Bob Marley’s Utopian world can be backdated that far.)

If we were really honest with ourselves, and comfortable and confident enough to accept our mottled past, most of us would admit to having such mixed, multiple origins too. Scratch the skin of any Southeast Asian and one would find the multiple, overlapping bloodlines and personal narratives of all of Asia beneath. Yet the impact of Empire, and the advent of the modern (post)colonial state, has rendered us boxed-in, compartmentalized, classified and registered subjectivities.

Living as we do in the postcolonial age as both modern citizen-subjects and inheritors of a premodern fluid past, no wonder these tensions come to the surface once in a while. And recently it did so with a vengeance.

More Sulus to come

What the Sulu-Sabah debacle has done is bring to the fore what can only be described as the growing gap between two virtual ASEANs: On the one hand an ASEAN that is connected via the modern communicative infrastructure that is used by the region’s technocrats, business elites, middle-class professionals and globe-trotters who can afford to fly; and, on the other hand, an ASEAN that is populated by hundreds of millions of other ASEAN citizens who may feel that the capital-driven march towards globalization has left them behind.

In the case of the former, we see the emergence of a new generation of ASEAN-minded citizens whose sense of belonging across the region is rendered all the more comfortable by the poolside bar and their sushi power-lunches; in the case of the latter their dreams of becoming global citizens extend only as far as the gated compounds of the rich which they cannot ever penetrate, and the cold glass window of the shopping malls brimming with luxury goods they can never afford.

Somehow, the nation-states of ASEAN need to bring these two communities together, lest we end up living in a bifurcated ASEAN divided against itself.

I am not condemning ASEAN here, for I consider myself a committed ASEAN-ist. And while there are those who think that ASEAN has gone past its sell-by date and has nothing left to offer, I would beg to differ. For all of ASEAN’s failings, weaknesses and internal contradictions; it did do what it set out to do, which is to prevent wars between states from 1967 until today.

Look across the globe today and we will see that ASEAN and the European Union are perhaps the only multi-national bodies that have managed to prevent conflict when so many other regions were blighted.

But unlike the EU, the convoy of states that make up the ASEAN flotilla is a diverse one indeed. For a start, there remain enormous differentials in terms of GDP and income levels across the region. Then there remains the fact that structurally the nation-states that make up the ASEAN flotilla are so very different too, ranging from republics with centralised rule, monarchies, constitutional monarchies and federations.

The very fact that the ships of the ASEAN flotilla have managed in sail in more or less the same direction for more than four and a half decades is, for me, an achievement in itself.

But from the very beginning until now, ASEAN has been made up of nation-states whose cordial relations were maintained only because these were states that were interacting with each other according to well-established norms of diplomacy and statecraft.

Grey zones

But are we any closer to a people’s ASEAN, that takes into account the complex and complicated nature of the communities and diasporas that criss-cross, overlap and inter-marry across the region? Can ASEAN, in short, handle the radical contingency within itself, that it has been in denial of from the start?

The current impasse related to the Sabah-Sulu issue shows how nation-states can fumble and fail when it comes to dealing with the primordial attachments of communities whose histories can be traced back before the advent of the modern nation-state.

And if we look about the region, we can see many of these grey zones that dot the ASEAN map today: The Hmong people for instance can be found straddling the borders of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia; like the Karens who straddle the divide between Thailand and Myanmar. The communities the live across the Malaysia-Thai border likewise trace their roots to the ancient Buddhist federation of Langkasuka. And then there are people like the Bajao Laut sea nomads, whose myth of origins traces them back to Sulawesi, Philippines and the Straits of Malacca.

These are not tribes from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, but real communities, with real lives, real histories and real memories that confound and challenge the simplistic logic of modern governmentality; and yet in their own way they are really at the forefront of the borderless ASEAN that ASEAN states wish to create.

So how do we get over this epistemic hurdle, and wrap ourselves around the idea of fluidity? Can we ever live with wet, flexible borders?

Build bridges

I have written before that I am not against the nation-state, despite my irritations about its slowness and clumsiness when it comes to dealing with nuance and variability. The nation-state is a clumsy tool, and expecting it to do sophisticated things is akin to performing brain surgery with a jackhammer.

But unfortunately it happens to be the only tool we have at the moment, to perform the bricolage work that we need to do if we are going to take our ASEAN region one step further.

Occasionally the nation-state does surprise me, and I was elated to hear that Malaysia and Singapore are about to embark on a massive project involving an undersea tunnel and high-speed rail link that would link up Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, all within the space of 90 minutes. The implications of this project are enormous: It would render geography effectively redundant, as millions of Singaporeans and Malaysians would be able to live and work (and love, and date, and marry and procreate) in a shared virtual space where nationality, nationhood, citizenship and belonging would all be thrown into the high-speed blender of postmodernist deconstructionism.

In the decades to come, mass movement on such a scale would radically alter how the citizens of these two countries view each other, and themselves in turn. It would give rise to a new kind of subjectivity and perhaps new forms of identity, nationhood and belonging; bringing us back to the premodern world of a fluid Southeast Asia where hybridity was the norm.

Though here lies the catch: Such ventures work only when the states involved have agreed to lower their defenses, have developed enough surplus comfort to cease viewing the other as the potential enemy, and when there is capital to propel the process.

Marginalizing the majority

But what about the rest of ASEAN, that may be made up of hundreds of millions of citizens for whom such gemstones of postmodernity are a luxury they can ill-afford? If globalization is to be spearheaded by the forces of capital, are we not in danger of marginalizing the majority of ASEAN citizens who may never get to enjoy even a sniff of the globalization pie?

This is how I view the current crisis in Sabah-Sulu, where those who felt that they were not given a slice of the pie of the peace accord have instead fallen back on the older narrative of essentialist identity and primordial entitlements, as a last-ditch attempt to anchor themselves before the tsunami of capital-driven progress. And remember: there are many pockets of uneven development across the region, with simmering tensions ready to boil over too.

If this discrepancy between capital-driven globalization and poverty-induced stagnation/inertia is not addressed, ASEAN will develop into a patchy map made up of inter-connected islands of hyper-development, swimming in a vast sea of poverty, isolation, marginalisation and disempowerment.

This does not bode well for our region’s future, and in the long run even the be-cushioned yuppies in their plush condos will feel the pinch, if their cocooned lives in their gated communities can only be preserved by an army of bodyguards and electric fences.

I honestly don’t know if there is a magic formula that can solve this problem, and deliver us all to the happy promised land of postmodern multiculturalism laced with candyfloss and gummy bears. But I believe that with ASEAN integration coming so soon (countdown to the ASEAN Community in 2015), the nation-states in ASEAN had better put their heads together and do some thinking out of the box.

ASEAN’s states are young states, despite the antiquity of our collective regional past. And young states tend to be cautious in their approach to dealing with contingency and variables, for they are painfully aware of their vulnerabilities. The Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Malaysia, are all states whose births were painful – having had to deal with civil wars, uprisings, insurgencies in the first decades of their youth. This has led to a culture of paranoia and caution among their technocrats and securocrats, whose proclivities towards policing leads them to seeing hidden enemies and conspiracies everywhere.

In an ideal world we might be able to press the “pause” button, let the rest of the world pass us by, and wait a century or two as we get to know one another better and grow more comfortable with each other. European integration was the result of hundreds of years of wars, and tens of millions of victims, and the Europeans finally came to adjust to the fact that they are, in the end, Europeans.

ASEAN however does not have another hundred years to wait. By the end of this decade we are likely to see the decline of American economic-political power and the rise of China on our very doorstep. The dominant paradigm that governed our understanding of our place on the map of geopolitics has become redundant, and as late as the 1990s nobody in the region expected China to be the no.1 trading partner of almost all the countries of ASEAN, as it has become now.

If ASEAN is going to be able to keep its flotilla of states sailing together into the choppy waters that lie ahead, its leaders had better be able to rethink some of their settled assumptions about nationhood, nationality, citizenship and identity. The very same governments that have been responsible for producing all the school history textbooks that have been teaching our students the histories of their countries, and only their countries, may wish to lay more emphasis on the connected history/ies of Southeast Asia instead.

The very vocabulary that is used in the textbooks of our schools have to be altered somewhat, so that the neighbor is seen as a neighbor, and not a foreigner, and so on. In other words, the very vocabulary and epistemology of ASEAN needs to be re-appraised, and soon too.

Of course we acknowledge the limits of the state and state power; and we recognize that despite the maximalist ambitions of states they are not as powerful as they think. (I maintain that they are clumsy tools, as I mentioned earlier). For no state, despite the power it may amass in its arsenal of state-power, can legislate laws that compel their citizens to love their neighbors. (States can’t even force you to love your mother, for heaven’s sake.)

But states can encourage those who love their neighbors by opening up spaces where ASEAN citizens who wish to connect on a people-to-people basis can meet, connect, integrate and develop.

This may be one of the ways through which the modern postcolonial state in ASEAN can deal with the complexity of our hybrid fluid society, and the fact that our motley mix of communities and ethnicities have always been interacting with each other, until today.

This time has come, I believe, for the nation-states of ASEAN to address the complexity of our societies that we have denied for so long. So my question is: Are we, ASEAN citizens, and are the states of ASEAN, ready for multiple citizenship?

It may not happen tomorrow, but it is a question we ought to begin asking nonetheless. – Rappler.com

Dr Farish A Noor is Associate Professor at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU University Singapore. The opinions expressed here are his own and do not necessarily represent his institution.

All images of the author.

Click the links below for more opinion pieces in Thought Leaders:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.