SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Plummeting rice prices: How will our rice farmers cope?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/F8F568FBA0D94EB19738AD7D47478DB5/img/30AC8C4974CA4CC5A9F87772D698C860/Freefalling-rice-prices-september-5-2019.jpg)

It’s a very bad time to be a rice farmer.

A precipitous drop in rice prices is endangering the incomes and livelihoods of more than two million Filipino rice farmers nationwide.

Many blame the Rice Tariffication Act, which President Rodrigo Duterte signed last Valentine’s Day.

The law replaced the old import quotas with tariffs, so that anyone can import rice as long as they pay the requisite tariffs or import taxes. (READ: Will rice tariffication live up to its promise?)

But more than 6 months after its implementation, some government economists were reportedly “surprised” by the magnitude of the recent price drops.

Has rice tariffication gone overboard? What can government do to help those whose boats were not buoyed up – but instead submerged – by the tide of cheap rice from abroad?

Free fall

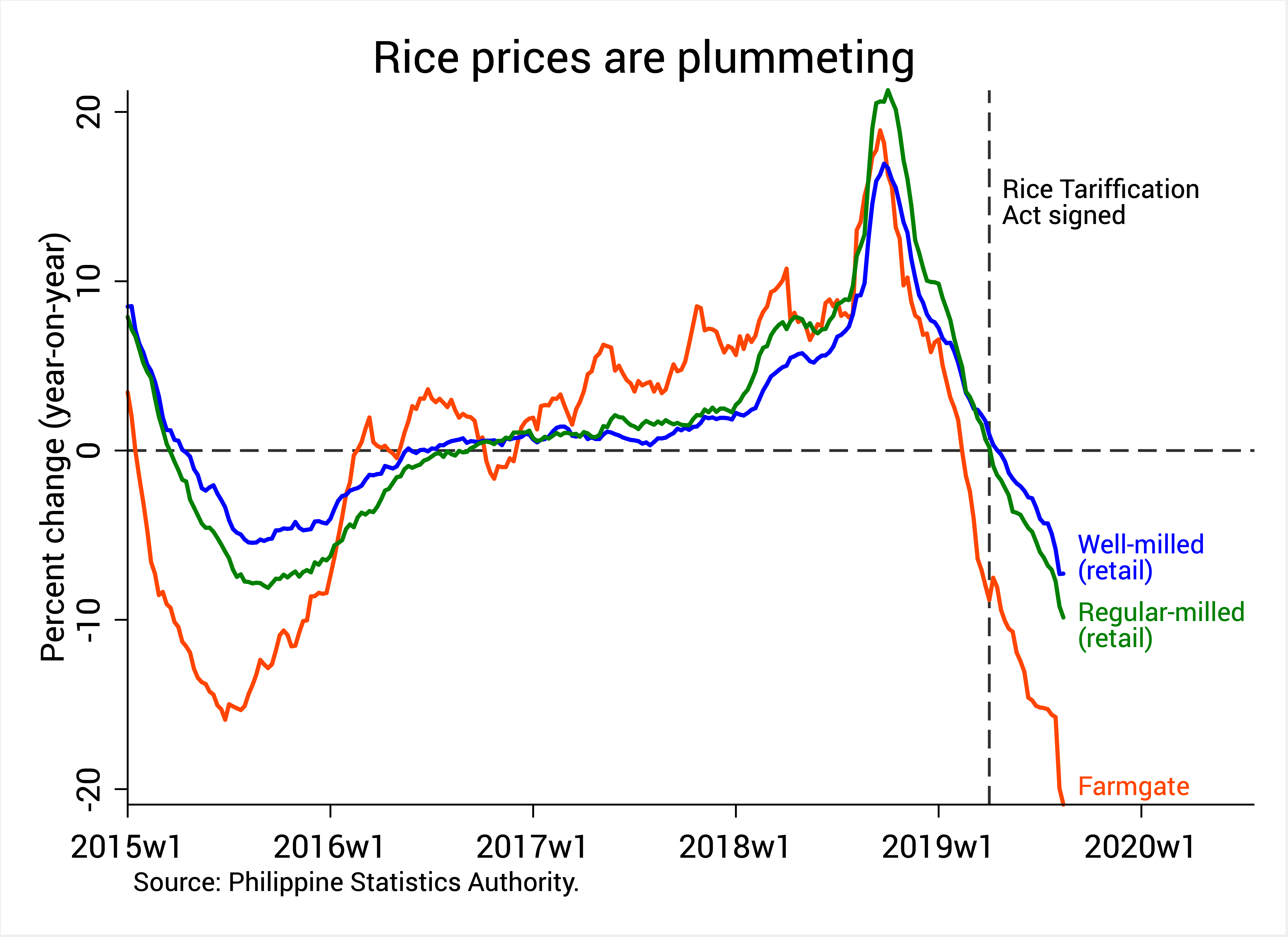

Data confirm that rice prices are dropping like a rock.

As of mid-August the average farmgate price of palay nationwide was recorded at P17.62 per kilo.

Figure 1 shows that’s a whopping 21% drop from last year. Retail prices of regular-milled and well-milled rice, by contrast, have dropped by 10% and 7%, respectively.

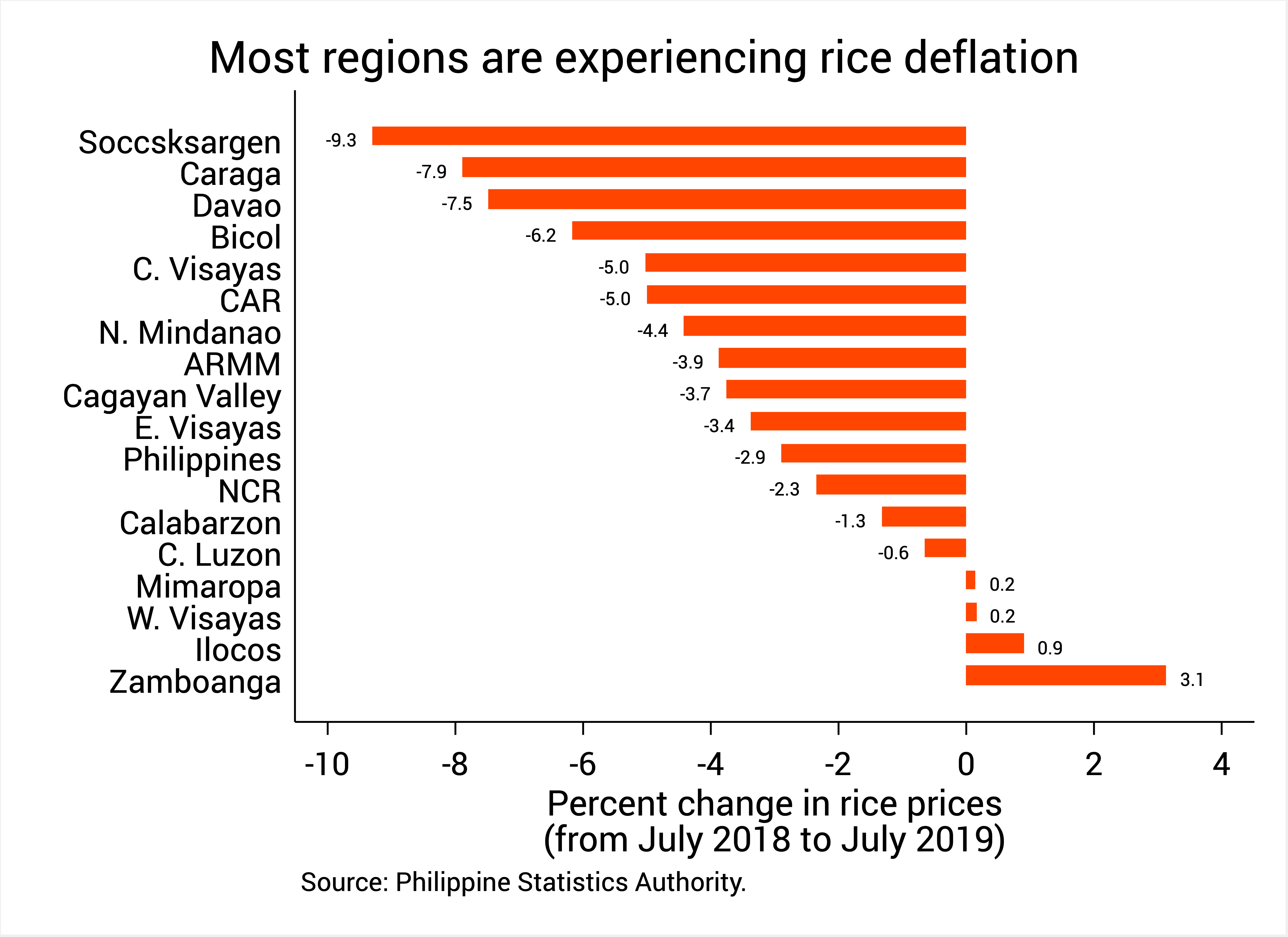

There’s considerable variation in rice prices across the regions. Farmgate rice prices have reportedly plummeted to as low as P9 per kilo in Pampanga and P7 per kilo in Nueva Ecija and Bataan. Farmers fear rice prices will only drop further come next harvest season.

Figure 1.

There are many reasons behind the free fall of rice prices.

First, we’re coming from a period of unusually high rice prices. Around September last year farmgate prices were actually rising by as much as 19%. This was due largely to the near-depletion of subsidized rice, which propped up commercial rice demand and prices.

Second, the harvest season kicked in late last year, accounting for the drop of rice prices even before 2019.

Third, the Rice Tariffication Act, as expected, inundated the market with cheap rice from abroad. This is in keeping with the law’s primary goal of making rice more affordable for the vast majority of Filipinos.

Lower rice prices are especially good news for the poorest fifth of Filipino households, who consume as much as a fifth of their budgets on rice alone. (By contrast, the richest fifth of households spend only about 5% of their budgets on rice.)

Rice tariffication was also touted as a way to combat last year’s runaway inflation. Figure 2 shows that most regions are now experiencing rice deflation, with prices decreasing the most in Soccsksargen, Caraga, and Davao.

Even so, retail prices have yet to drop to P27 per kilo as initially foreseen by the economic managers.

Figure 2.

While lower rice prices benefit rice consumers, they hurt rice producers, mostly our local farmers.

Economic managers justified rice tariffication by arguing rice-farming households are, in fact, “net purchasers” or “net consumers” of rice. Simply put, they consume more rice than they produce. Hence, lower rice prices should benefit them in the end.

But Figure 1 shows farmgate prices are dropping 2 to 3 times faster than retail rice prices. For anyone whose income is pegged to farmgate prices, this is a recipe for disaster.

Even without rice tariffication, farmers are already among our most economically vulnerable workers.

A friend who teaches in Nueva Ecija told me some rice-farming families have already stopped sending their kids to school on account of depressed rice prices.

Coping mechanisms

Government officials are now scrambling to ameliorate the impact of rice tariffication on our farmers. But will their proposals work?

1) Rice fund

In anticipation of the hurt it will cause local rice farmers, the Rice Tariffication Act provided for a P10-billion fund called the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF).

Financed from the tariff revenues, RCEF is to be earmarked for machinery, seeds, and interest-free loans that will help our farmers stand on their own feet once we’re flooded with cheap rice imports.

But in a recent Senate hearing, Senator Cynthia Villar expressed dismay at how RCEF has been handled thus far by the budget and agriculture departments.

Apart from budget issues, some experts also doubt if spending on machinery and seeds is best for improving the competitiveness of our farmers, vis-à-vis credit and insurance. Dr Ramon Clarete of the UP School of Economics suggests using conditional cash transfers.

Past agricultural funds were also corruption-prone (think of the P728-million fertilizer fund scam). Just how corruption-proof is RCEF?

2) Price support

Various forms of price support are also on the table, with varying levels of feasibility.

First, some say government can boost the incomes of embattled farmers by aggressively buying palay at subsidized prices.

After all, the National Food Authority (NFA), which previously monopolized rice importation, is still around. In fact, the NFA is mandated by the Rice Tariffication Act to “maintain sufficient rice buffer stock.

But some say that the RCEF – which aims to develop farmers’ competitiveness – is far superior compared to simply handing out money to farmers.

Some farmers are also clamoring for a price floor on rice, or a minimum price by which rice must be bought from them. They suggested that it be set at P10-P12 per kilo to match current production costs.

When such price floor kicks in, Econ 101 tells us government will have to contend with perennial rice surpluses as artificially high prices induce farmers to produce more than consumers will buy.

Farmers can always dispose of these surpluses by selling them in the black market at prices lower than the price floor.

Unless government can commit to always buy such surpluses, it will be very hard to enforce and sustain such a price floor.

3) Prohibitive tariffs

Finally, Senator Imee Marcos suggested that government raise tariffs against ASEAN or non-ASEAN countries.

She said, “If South Korea and Japan have imposed import tariffs of 500% to 800% to protect their local farmers, why can’t we?”

But such prohibitive tariffs will, by themselves, cause more distortions in the market and defeat the very purpose of rice tariffication: to make rice more affordable for millions of Filipinos.

Good intentions not enough

Unquestionably, we need to support all farmers whose incomes and livelihoods are now hurting because of rice tariffication.

Yet at the same time we shouldn’t demonize rice tariffication per se. Retail rice prices are also going down, albeit to a lesser degree than farmgate prices. This could go a long way to reduce overall hunger and poverty.

Politicians must also tread carefully when it comes to helping our farmers. Policies driven by good intentions, yet lacking in careful thought, can often do more harm than good. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.