SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Duterte’s foul attacks on big business: What is he up to?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/E4496F2A41E348DCB60DA8FE6E2D3DA4/dutertes-foul-attacks-on-big-business--december-19-2019.jpg)

This year Newsbreak, Rappler’s investigative and in-depth section, is capping off 2019 with a series of stories threaded by the theme of lawlessness. (READ: 2019: Lawlessness in the Philippines under Duterte)

Whether in the halls of Malacañang, in our streets, or in our open seas, the Duterte government has demonstrably and consistently disdained the rule of law and our Constitution.

But in this piece I argue there’s one more type of lawlessness that has plagued us in recent years: economic lawlessness.

You might take this to mean situations where private firms take matters into their own hands and disregard laws and regulations.

But here I’m talking about the fact that the Duterte government has shown a propensity to disrespect contracts, ignore property rights, and harass businesses.

Duterte, of course, is no stranger in antagonizing the private sector. (READ: Look back: Duterte’s tussles with big business)

In this piece let’s focus on Duterte’s recent attacks on 3 big corporations – Manila Water, Maynilad, and ABS-CBN – and try to glean what he’s up to.

Water firms thrown in the deep end

Duterte’s attacks on Metro Manila’s two water concessionaires – Manila Water and Maynilad – are a perfect example of economic lawlessness.

More than a week ago the two firms were shocked to learn that their concession agreements, which allow them to operate as Metro Manila’s water distributors, were cut short by their regulator (the Manila Waterworks and Sewerage System) from 2037 to 2022.

That’s 15 years earlier than stipulated in their concession agreements with government.

This revocation is a huge blow. Both firms are already strategizing and laying out capital for the next 18 years, only to realize all their plans have rested on shifting sand.

Maynilad’s Vice Chairman Isidro Consunji even hinted that both companies may go bankrupt if negotiations break down.

This terrible plot twist was the culmination of attacks from Duterte himself.

Earlier Duterte fumed at the water firms because the Permanent Court of Arbitration in Singapore ordered the Philippine government to pay Manila Water P7.39 billion. This was because the government had unjustly blocked the firm from raising water rates before.

In the wake of this decision, Duterte branded the water firms’ owners as “oligarchs” and “economic saboteurs.” Later Duterte even warned he might order a military takeover of such firms.

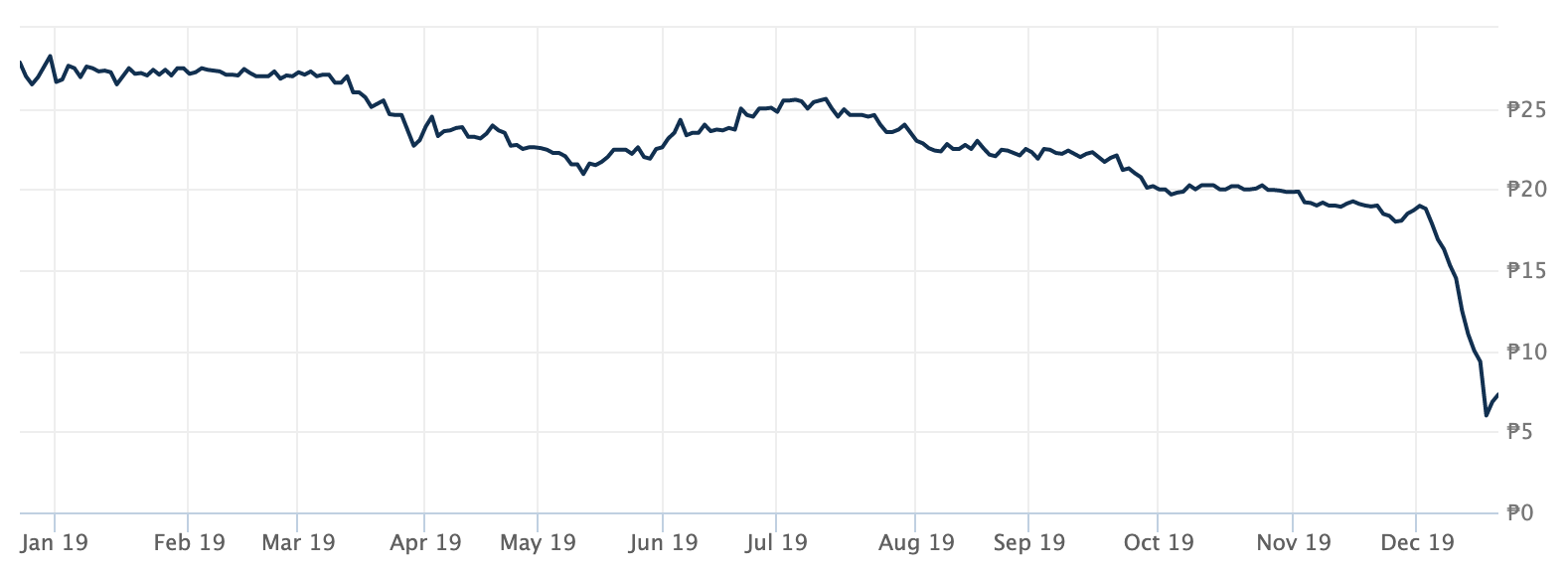

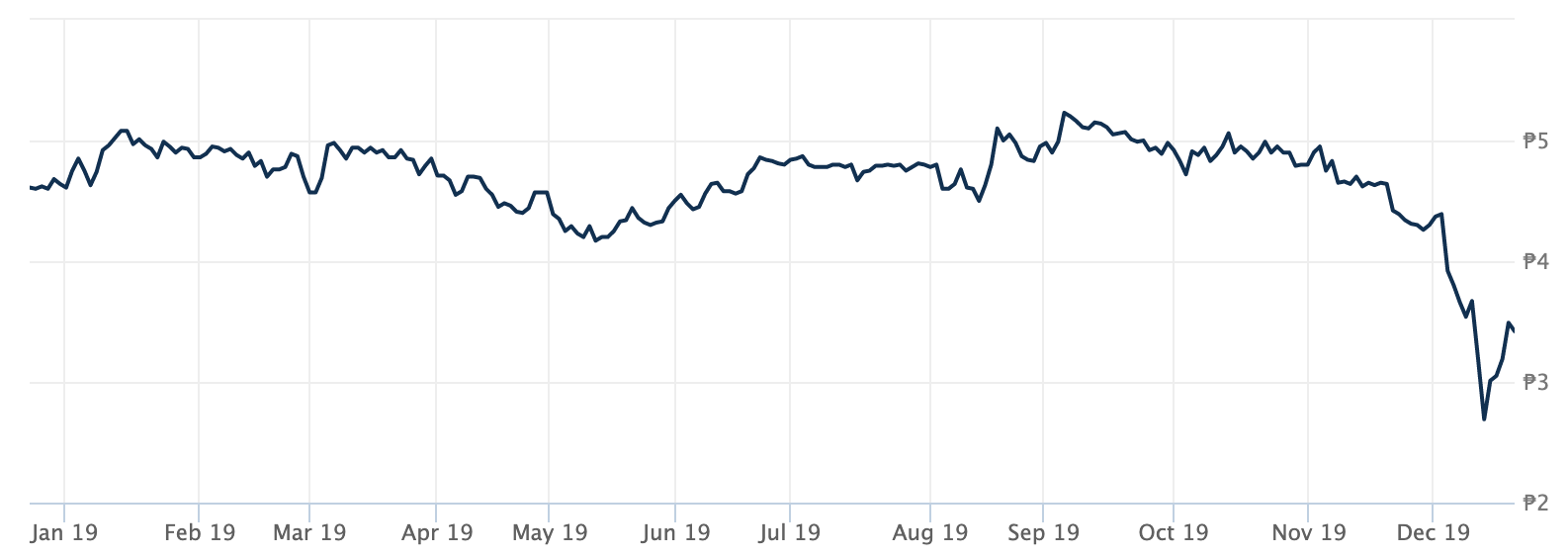

Unsurprisingly, the stock prices of both Manila Water and Metro Pacific Investments Corporation, which owns much of Maynilad, recently nosedived (Figures 1 and 2). Manila Water’s stock price even dropped to its lowest level in 12 years.

It’s bad enough that these plummeting stock prices represent billions of losses for shareholders in both companies. But it also threatens the pensions of millions of private employees enrolled in the Social Security System, which has substantial investments in Manila Water.

Figure 1. Manila Water stock price. Source: Barron’s.

Figure 2. MPIC stock price. Source: Barron’s.

Above all, the revocation sends a bad signal to investors (here and abroad) that the Philippine government cannot keep its long-term contracts with the private sector and can capriciously change the rules in the middle of the game.

This cannot be. Imagine a basketball game where the referee suddenly announces traveling is permissible and each team can now have more than 5 players at a time.

Just as basketball rules can’t change in the middle of a game, so rules between the government and the private sector can’t change on a whim.

With our business sector enveloped by a thick fog of uncertainty, which investors will now dare to strike deals with the government?

ABS-CBN’s fight for survival (again)

The Duterte administration is also flexing its muscle toward another big business, namely ABS-CBN.

Next year ABS-CBN’s 25-year franchise to operate as a media firm – specifically to “construct, operate and maintain…television and radio broadcasting stations in and throughout the Philippines” – will be up for renewal by Congress.

But for years now Duterte has repeatedly threatened to rally lawmaker friends and block said renewal.

Most recently Duterte said, “Ang iyong franchise mag-end next year. If you expect ma-renew ‘yan, I’m sorry. (Your franchise will end next year. If you expect it to be renewed, I’m sorry.) I will see to it that you’re out.”

As a result of this latest presidential threat, ABS-CBN’s stock price also dipped (Figure 3), albeit nowhere near the nosedive of Manila Water and MPIC’s stock prices.

Figure 3. ABS-CBN stock price. Source: Barron’s.

Of course it’s entirely within Congress’s discretion to renew ABS-CBN’s franchise or not.

But Duterte’s ostensible reason for attacking ABS-CBN seems unreasonably shallow. Duterte once claimed the station committed swindling for failing to air some of his ads during the 2016 elections.

More important, Duterte’s attack on ABS-CBN brings to mind similar bullying by the Marcos regime against the Lopezes.

Recall that former president Ferdinand Marcos, absent formal charges, had ordered the arrest of Eugenio “Geny” Lopez Jr. in 1972, shortly after martial law was declared, in a bid to neutralize the political power of the Lopez clan.

In exchange for Geny’s release, Geny’s father (Don Eugenio Lopez) was forced to give up many of their businesses – including Meralco and the progenitor of ABS-CBN – to enrich Marcos and his cronies.

Even with Don Eugenio’s capitulation, Geny was in fact not released and only managed to escape prison in 1977, five years after his arrest.

Marcos’s forcible takeover of the Lopezes’ businesses and assets was clearly a predatory act. Fast forward to present day, Duterte is repeating history by attacking ABS-CBN.

Whether Duterte’s attack is predatory, too, remains to be seen. Yet his actions show just how the state could use its might to intimidate, corner, and beat to a pulp a private company – just because it can.

Ulterior motives

A number of people speculate Duterte’s slew of attacks against big businesses is part and parcel of a larger strategy to prop up his own cadre of budding oligarchs.

That is, by attacking big companies and devaluing their stocks, Duterte might be opening an opportunity for his wealthy friends to take over these embattled companies.

By “friends” we mean, for instance, Davao tycoon Dennis Uy and former senator Manny Villar. Both are multibillionaires and their business empires have noticeably expanded of late.

Just when ABS-CBN’s fate is hanging by a thread, Dennis Uy is reportedly eyeing an expansion into media and telecom. Some even go on to say Uy may be the “white knight” who will ultimately save ABS-CBN next year.

Meanwhile, amid the impending exit of the current water concessionaires, the Villars are venturing into water what with Prime Water. Duterte was even quoted as saying the Villars might one day enter water distribution in Metro Manila.

If these speculations turn out to be true, then Duterte’s purported hatred towards oligarchs proves merely illusory. He’s just weeding out the old to make way for the new. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.