SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The Philippines has just achieved another key milestone — an upgrade to “investment grade” status. Investment grade typically ushers two possible benefits. First, the country’s risk premium (the extra interest rate that international lenders charge for relatively weaker macroeconomic fundamentals like tax collection, debt sustainability and low and stable inflation) could decrease, which means there could be a lower cost of borrowing, with positive knock-on effects for the public sector (i.e. debt sustainability is enhanced) as well as on firms with access to international finance (i.e. typically the larger firms).

A second possible boon is the increase in domestic and foreign investment, due also to lower interest rates as well as to the “seal of good macroeconomic management” that investment grade status implies for many investors. Analysts contend that this second effect was already pre-empted by those investors who anticipated the country’s credit upgrade. The question, however, is whether these capital inflows are speculative or longer-term; and we have already experienced some hiccups in our stock market in recent weeks.

So far, and despite the euphoria, the facts on the ground prompt a balanced interpretation of what the credit upgrade will bring. One question is whether and to what extent it will expand credit access in ways that would promote inclusive growth—such as by lending to SMEs, or small and medium scale enterprises, (the bulk of which employ poor and low income people) and to the agricultural and manufacturing sector (which typically helps absorb the same group mentioned).

As of end-2012, about one-third of outstanding corporate loans by universal and commercial banks went to firms from the real estate, financial institutions and business services sector. In contrast, a mere 6% went to the agriculture and forestry sector, and about 19% to the manufacturing sector. And in both cases, much of these loans probably went to larger firms rather than SMEs. Large firms also contribute to inclusive growth; but most agree that without the SMEs, this would barely make a dent on poverty.

A study by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) reported that as of September 2010, banks’ total loans to SMEs amounted to about P290 billion. This is a meager 9% share of the total banks’ loan portfolio at that time. According to this study, SMEs’ access to finance is but one of many challenges they face (as I will explain further later).

In addition, the public sector is also enjoying relatively strong fiscal space with a deficit of only about PhP240 billion as of 2012. A credit upgrade allows the government to acquire even cheaper debt in the international markets. However, this benefit will be tempered by the recent policy of the Department of Finance to focus more on borrowing domestically.

So the gains to government of this investment grade status may be largely be reputational—unsurprising since international credit markets behave in a curious way: they are eager to lend to those that are not really eager to borrow (that’s demand and supply for you!).

But perhaps most important, when one looks at recent comparative foreign direct investment trends, the Philippines has indeed improved, but it still struggles to catch up with other ASEAN economies, including those with relatively poorer credit rating status.

Improving but not catching up

In 2012, the Philippines recorded a net FDI inflow of roughly US$2 billion, which is already an improvement over its previous average yearly net FDI inflow of about $1.5 billion during the last decade (2001 to 2010). However in that same year, Indonesia registered net FDI inflow of roughly $20 billion and Vietnam about $8 billion.

Both these countries are not being considered for investment grade, but they seem to be doing other things right so they’re landing these higher net FDI inflows.

Also, in Latin America, Argentina had a net FDI inflow of $11 billion in 2012 while in Africa, Egypt, despite its recent challenges, had $3.5 billion. Both countries have lower credit ratings than the Philippines.

Clearly, many other things go into the decision by foreign direct investors; and a country’s credit rating is not the only factor (nor necessarily the most important factor).

These facts combined suggest that even cheaper credit is not necessarily what will trigger investments—at least the kind that we’re interested in, which is a) NOT speculative; and includes: b) FDI to put fuel into our job generating engine; c) investments in SMEs to make sure that the jobs benefit many poor and low income underemployed workers; and d) investments in the agricultural sector to help strengthen our rural productivity, food security and help de-concentrate the onus of growth in the urban centers. (And as Economic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan has lamented, about 60% of GDP is concentrated in 3 areas in Luzon.)

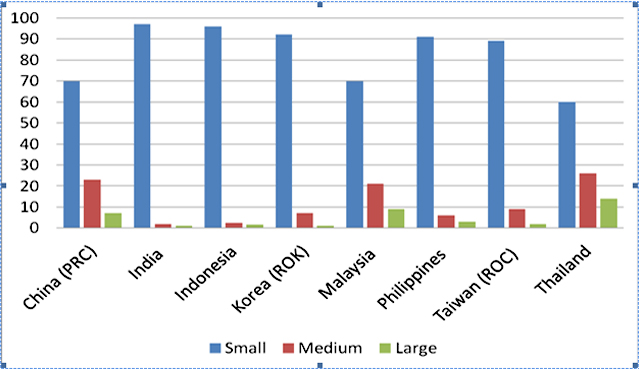

Most entrepreneurs I have spoken with consider investment grade status a boon for the government and larger firms. But it is largely inconsequential for the tens of thousands of micro, small and medium scale enterprises that comprise the bulk of the Philippine production sector. (See Figure 1 below)

Source: Asian Development Bank

Even the trickle down of cheaper credit will be just that—a mere trickle—if the banks do not lend to SMEs. Further, SMEs require many other bottlenecks unclogged, even more important to them than cheap credit. (In fact, these bottlenecks probably exacerbate the lack of willingness by banks to lend to many SMEs in certain regions with bad governance.)

SMEs and inclusive growth

In ASEAN countries, SMEs account for well over 90% of all enterprises, employ anywhere from 50% to well over 90% of the workforce, and contribute around 30% to 80% of the GDP in these countries.

Many developing countries have made small and medium enterprise development as one of the priorities of their economic agendas.

Despite their importance, SMEs continue to face various obstacles that hinder their growth. The efficient provision of public goods, the reduction in red-tape, corruption and onerous business registration procedures, and an altogether better regulatory and investment environment can help boost competitiveness and competition.

An environment that is friendly to doing business could enhance the firms’ ability to expand, innovate and generate pro-poor jobs.

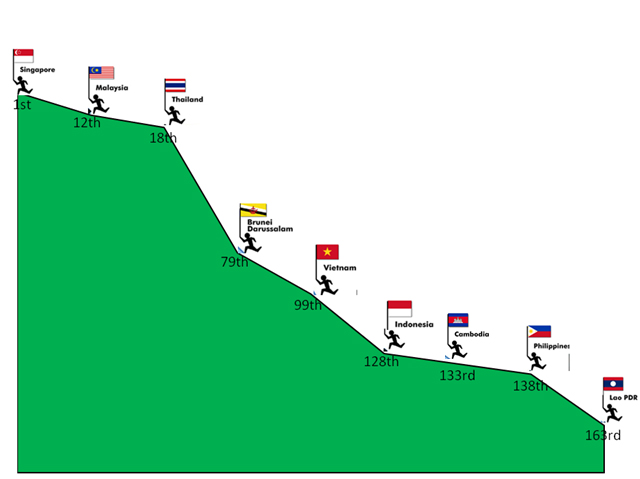

Countries in the East and Southeast Asia region can be found both in the highest and lowest rank clusters in Doing Business 2012 which measures the ease of doing business by gathering data on factors like ease of starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, etc. Out of 185 countries, Singapore and Hong Kong rank 1st and 2nd, while countries like Cambodia, the Philippines and Lao PDR are in rank 133, 138 and 163 respectively. (See figure 2 below)

Source: World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index 2012

Inappropriate or irrelevant regulatory constraints also cause many firms to remain small and informal. Estimates suggest that the informal economy in the Philippines is still quite large—it accounts for over 40% of total GDP and well over 70% of employment. This is the sector that barely feels any of the phenomenal growth the Philippines has witnessed during the better part of the last decade and past few years. This is also the sector that will continue to be left behind, if real structural changes are not pursued.

While the challenges are myriad, a clear area for action should be the stronger promotion of a pro-business environment across all local government units. An onerous bureaucracy is haven for corruption and rent-seeking. Various ongoing surveys of SMEs—including by SWS and also by the AIM Policy Center—show that corruption still affects about one in two SMEs, mostly in the context of local governance.

These practices deter investment, slow businesses down, weaken our economic competitiveness, and in due course, these kill jobs.

Ultimately, “matuwid na daan” (i.e. the “straight path” anti-corruption policy of government) should not just be about the absence of corruption. “Matuwid na daan” should be built on a solid foundation of a more efficient and coherent government infrastructure that provides public goods and services well. SMEs benefit the most from this kind of a level playing field. – Rappler.com

(The AIM Policy Center, in partnership with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada is presently collaborating with the top young researchers on SMEs in the Asian region, in order to empirically examine the bottlenecks SMEs face in their growth and expansion. The Enterprise Performance in Asia Project will examine hard data on corruption, financing, crisis resilience, innovation, gender equity, firm dropout and firm expansion among SMEs in Asia. The project will culminate in an international conference on SMEs and Inclusive Economic Development in November 2013. Inquiries about this project could be directed to POLICYCENTER@AIM.EDU.)

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.