SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] The flawed economics of Duterte’s partial Metro Manila lockdown](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/6734962DEE62411FAA68D762E155A978/flawed-economics-of-mmlockdown-march-15-2020.jpg)

To contain the further spread of COVID-19, on March 12 President Rodrigo Duterte put all of Metro Manila under partial lockdown (technically “community quarantine”) from March 15 to April 14.

Although certainly better than nothing, there are reasons to believe this partial lockdown – as designed by Duterte – will not be very effective in containing the disease.

Duterte’s partial lockdown also doesn’t provide any financial assistance for workers and businesses whose incomes and livelihoods will be wiped out by the resulting economic downturn.

‘Flattening the curve’

To contain COVID-19, epidemiologists around the world recommend “social distancing.”

This chiefly involves closing down schools, offices, malls and public places; banning mass gatherings; and encouraging or requiring people to go into home quarantine.

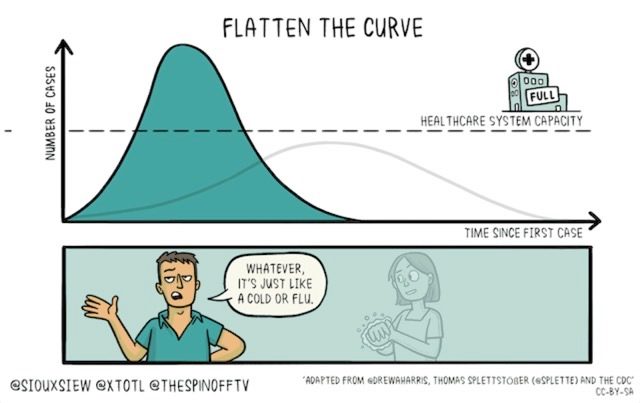

Social distancing works. Figure 1 shows that when done properly it spreads a viral outbreak over a longer period of time, but lowers the peak number of cases.

By “flattening the curve,” so to speak, we can prevent overwhelming our hospitals, exhausting frontline health workers like doctors and nurses, and preventing shortages of much-needed equipment like masks, gloves, and testing kits.

How to play your part minimising the impact of Covid-19, in one simple gif, thanks to @XTOTL & @SiouxsieW https://t.co/s2331Up39n pic.twitter.com/IDqnxAs5z5

— The Spinoff (@TheSpinoffTV) March 8, 2020

But besides social distancing, Duterte is also imposing upon us a partial lockdown. Movements in and out of Metro Manila are now restricted, but not totally prohibited.

Such lockdown is certainly better than nothing. It’s also much less economically disruptive than a mandatory lockdown, where we’re all trapped in our houses.

But because sealing off an entire region is next to impossible, a partial lockdown is inferior to, and less effective than, social distancing in containing a viral outbreak (see these animated visualizations).

Duterte’s partial lockdown also has too many weak points.

For instance, it still allows workers to go in and out of Metro Manila, provided they show identification at checkpoints. Considering there are about 3 million such transient workers – both those knowingly and unknowingly infected – it’s hard to imagine how this can effectively contain COVID-19 in Metro Manila.

Second, international flights will still be allowed under certain conditions. Unless government beefs up its contact tracing – as done in other countries – this might only spread the disease all over the place.

Third, Metro Manila’s mayors are mulling a curfew from 8 pm to 5 am. But the virus respects no schedule, and absent similar restrictions of movements during the day, the virus can still freely spread outside curfew hours.

Fourth, Duterte first announced the lockdown on Thursday, March 12, giving everyone two days to flee Manila and stay in the provinces before the curfew on Sunday, March 15. Hours before the shutdown, throngs of people were still jostling to catch flights at the airport.

Without knowing who among them were infected or not – because too few have been tested so far – this could have accelerated the spread of the virus outside of Metro Manila.

Recall that a similar thing happened in Wuhan City, the original epicenter of COVID-19. In time for their Lunar New Year holiday, some 5 million people, or half their population, fled before a city-wide lockdown was imposed. Experts believe this exodus raised the risk of spreading COVID-19 elsewhere, leading to the present pandemic.

All in all, Duterte’s community quarantine is not airtight and somehow defeats the purpose of containing the disease. One prominent doctor even called it “a mockery” of the concept of community quarantine.

Such policy would be much less useful if there are, in fact, already thousands of Filipinos already infected with COVID-19, but we’re just woefully clueless since too few of us have been tested.

Safety nets

Duterte’s partial lockdown also comes with it severe economic disruption that he doesn’t seem to have foreseen and prepared for.

For starters, malls have been advised to stop all their operations for a month. Considering that nearly two-thirds of our economy rests on consumption, and a third of our national output comes from Metro Manila alone, this spells a severe economic downturn.

Besides malls, lots of other businesses will suffer huge losses as customers stay at home over the next month, presenting severe cash flow problems that could bury lots of entrepreneurs – especially small and medium enterprises – in debt.

Millions of workers risk losing their incomes, especially those who live outside of Metro Manila. Lining up at the checkpoints will add to their commuting woes, eat up their working hours, and erode their incomes.

Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez blithely suggested that business owners should just encourage their employees to find a place to rent here in Metro Manila – as if that’s so easy for ordinary workers to do. Rents in the city are so much higher and will eat up a sizable part of their meager pay.

Even more insensitively, Secretary Lopez bade all workers in the informal sector – with no valid IDs to show proof of employment or business in the city – to just ply their wares and do business outside Metro Manila.

This again is glaringly anti-poor and sure to impoverish those just hanging on the edge of the poverty line.

The partial lockdown behooves the Duterte government to extend various forms of financial assistance to everyone whose incomes and livelihoods are in danger.

As I wrote in my previous piece, these safety nets may come in the form of temporary tax relief for businesses, as well as paid leaves, wage and rent subsidies, and cash transfers for workers, especially those in no-work-no-pay arrangements. (READ: Can Duterte ward off a coronavirus economic slump?)

All these may be folded into a comprehensive stimulus package bill by Congress. Thankfully, one such proposal amounting to P108 billion has already been put forward by Marikina Representative Stella Quimbo – formerly a health economist and professor of mine at the UP School of Economics.

Unfortunately – but unsurprisingly – Duterte himself said nothing about any such economic assistance during his nationwide address on March 12.

At this point are we even surprised he has a shortage of both economic competence and sympathy for the plight of the poor?

Priorities

With the death toll rising in the Philippines – according to the Department of Health there are now at least 11 deaths out of about 140 confirmed cases as of Sunday afternoon – an outbreak this drastic requires similarly drastic solutions. No less than UN Secretary-General António Guterrres said, “We must declare war on the virus.”

But Duterte’s partial lockdown has too many loopholes that do not ensure at all that the disease will be effectively contained. It’s also glaringly inequitable.

Finally, Duterte is dangerously treating this new public health problem as a law enforcement problem – as he did with the war on drugs.

Rather than pouring resources into the police and military, his government should instead be prioritizing support for hospitals and health workers (like doctors and nurses) who are at the real frontlines of this battle.

Rather than firearms and checkpoints, we need more masks and testing kits. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to an anonymous MD friend for valuable comments and suggestions. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.