SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

It was nearly 25 years ago that I got my first look at the diary of Ferdinand Marcos. I was an investigative reporter with the Los Angeles Times when about 3,000 pages of diary and other presidential papers were delivered to me in installments – on street corners, at a restaurant, in the lobby of an office building – all very cloak-and-dagger.

It was nearly 25 years ago that I got my first look at the diary of Ferdinand Marcos. I was an investigative reporter with the Los Angeles Times when about 3,000 pages of diary and other presidential papers were delivered to me in installments – on street corners, at a restaurant, in the lobby of an office building – all very cloak-and-dagger.

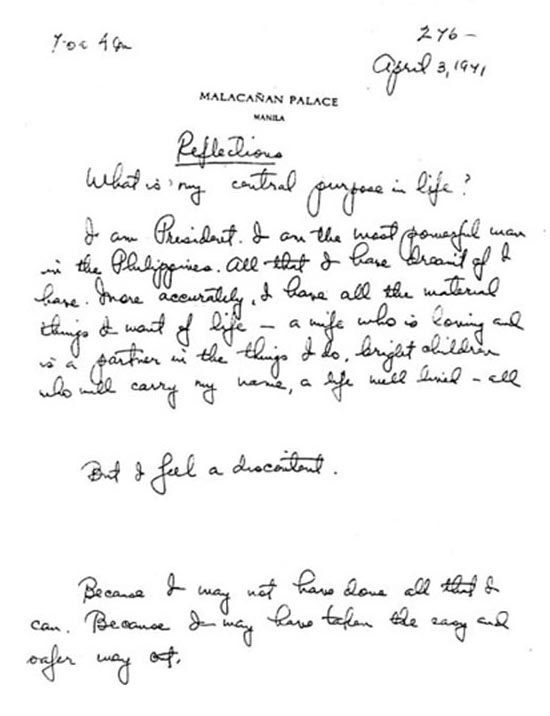

The documents were a journalist’s gold mine. I found bribery receipts and coded accounting reports recording official corruption. There were poems and love notes to First Lady Imelda and the Marcos children interspersed among Ferdinand’s plans for repression and dictatorship.

The diary itself contained the president’s private musings about power and his messianic calling to “save the Philippines” from an exaggerated threat of communist insurgency. Here, too, was compelling evidence of Marcos plots against political rivals, the press, and anyone who dared to criticize his administration.

But what caught me most by surprise were the lies – blatant, bald-faced, and occasionally comical. It turns out that while Ferdinand Marcos was lying to the world and to the Philippine people, he was also lying to his own diary.

As a writer trying to assess the news value and historic significance of the president’s journal I had to ask myself: what can be learned from a diary riddled with falsehoods and self-serving fictions?

Time has helped clarify the answer. Today I can see that his lies actually reveal a greater truth: Marcos was a dictator at heart long before he was a dictator at gunpoint.

In 1970, after the Manila Times criticized harsh police actions against anti-Marcos demonstrators, the president grumbled in his diary that the newspaper’s editorials amounted to support for “revolution and the communist cause.” He summoned a group of prominent business leaders to Malacañang.

“I asked (them) to withdraw advertisements from the Manila Times,” he wrote in his diary. “They agreed to do so.”

At a palace reception barely a month later, Manila Times publisher Chino Roces confronted Marcos about pressuring advertisers to drop their accounts. The president denied it.

“I had nothing whatsoever to do in suggesting the cut of advertisement,” the president wrote that night – only 36 pages after writing the opposite.

The president’s romantic affair with American actress Dovie Beams turned to public scandal that same year, prompting a torrent of denials to his diary and to Imelda. “I am being blackmailed,” Marcos wrote in his diary, calling it “a diabolical plot” that he blamed variously on his political rivals and the CIA.

After Dovie appeared before the Manila press corps to play taped recordings of her lovemaking session with the president, Marcos still insisted in his diary that the claims were “patently false.” And to punish the United States, he told a bewildered American ambassador that Washington’s military bases agreement with the Philippines would have to be renegotiated.

When an elderly delegate to the 1972 constitutional convention made a dramatic public display of returning unspent bribe money that he said came from Imelda and other Marcos loyalists, the president raged publicly and privately. It was, he wrote in his diary, a “dastardly act to malign my family” by what he called “a tool of the opposition.”

A few days later, federal police raided the delegate’s home and claimed to find US$60,000 stashed in a bedside drawer. He and his family said police planted the cash, a suspicion shared, according to a poll, by 80 percent of the public. Still, the ailing 72-year-old was arrested.

Marcos told his diary that the bedside loot was a “lucky discovery” and that the old man’s arrest was “poetic justice.”

But years later, documents tucked in with Marcos diary pages would prove otherwise. The papers contained accounting records of a massive bribery scheme, referred to around the palace simply as the “envelope campaign.” The records helped Marcos keep track of his payoffs to some 200 convention delegates – even as he was urging prosecution of the one delegate who refused to be bought.

More than a year before he would declare martial law, Marcos tested the limits of his presidential authority in a case that came before the Philippine Supreme Court late in 1971. Amid widely disputed claims of a communist insurgency threat, Marcos wanted the court to sanction his power to declare a national emergency and suspend the constitution.

The stakes were high. Marcos feared that a closely divided panel could leave the matter muddled and undermine his authority, especially with military leaders. So, in truly Machiavellian fashion, he enlisted one of the 11 justices as a spy.

Fred Ruiz Castro, the president’s double agent on the high court, provided inside information for nearly three months. In late-night visits to the palace, recorded by Marcos in his diary, the judge shared updates on the shifting legal positions of fellow jurists and offered advice on strategies to win over the skeptics. He even conducted a mock hearing one night to prepare Marcos’s solicitor general for an appearance the next day before the full court.

When the controversial – but unanimous – ruling was finally issued, Marcos celebrated in his diary: “This is a red letter day.”

He went on to take personal credit. “The justification before the Supreme Court was prepared by me,” he wrote. He made no mention of his secret agent or the extraordinarily improper lobbying offensive that had assured unanimity.

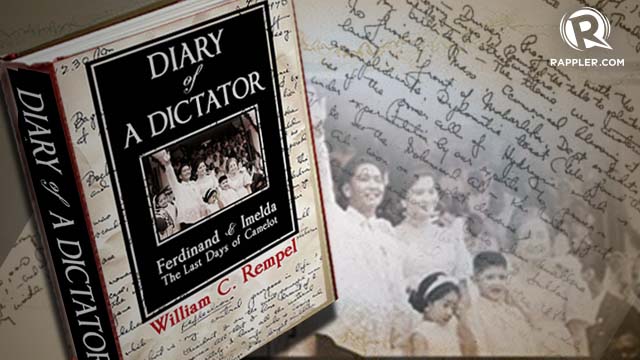

Despite such lies – of commission and omission – I regard the Marcos diary as historic treasure. It says so much, not only about the dictator that always lurked in Ferdinand Marcos, but also about the vulnerability of democracy wherever fiction trumps the truth. – Rappler.com

William C. Rempel is author of the new e-book, Diary of a Dictator – Ferdinand & Imelda: The Last Days of Camelot, an updated and revised version of his 1993 book, Delusions of a Dictator (Little Brown & Co.) He also is a former investigative reporter for the Los Angeles Times and author of At the Devil’s Table – The Untold Story of the Insider Who Brought Down the Cali Cartel (Random House).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.