SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

ZAMBOANGA CITY, Philippines – They ran, on the morning of September 9, 2013, just as the bullets began peppering the village of Santa Barbara. She and her family carried nothing when they left home. They headed for a nearby church; they were told it was a sanctuary for the displaced. The family was turned away. Muslims, they were told, were not welcome.

Word came that Santa Barbara had been razed to the ground. There was no going home. Those who tried were caught in the crossfire between the government and a splinter group of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF).

The fighting lasted 21 days. At least 140 were killed, over 10,000 homes were destroyed, and more than 120,000 people were forcibly displaced.

Sheila was almost 9 months pregnant on the day the mortars fell. They walked for hours, then joined others who found their way to the Enriquez Grandstand in the heart of the city.

Sheila’s family slept on the bleachers until donors sent in tents, plastic sheeting, and rope. The family hung walls of blankets, lined up for food packs and showers, and waited for the war to end.

Watch Sheila’s story: The children of Sta. Barbara

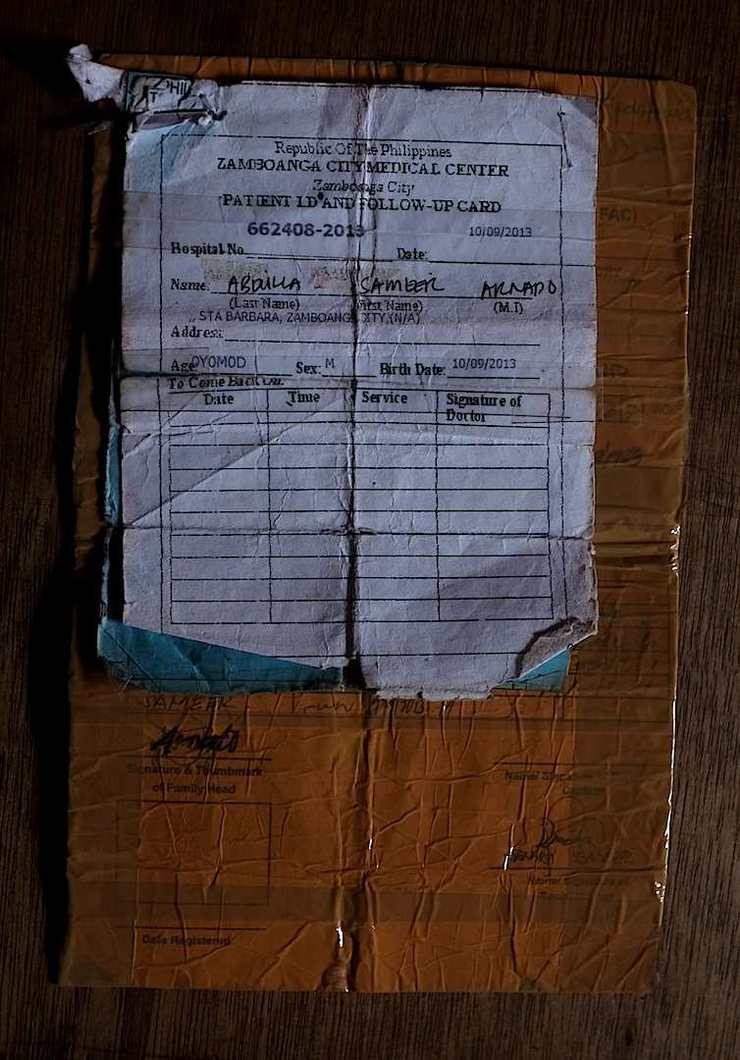

Sheila gave birth in October 2013. They named the boy Sameer. He was a happy boy, said his mother, the youngest and the loudest, apple of his father’s eye.

The city government began to organize the grandstand, building shelters into the bleachers and on the field. The extended Abdulla family, 14 in all, was given a temporary unit – a cross between a tent and a shed – at Zone 1, by the bleachers. Food was difficult, conditions appalling, but there was water and electricity. The family had little choice. Their home in Santa Barbara had been razed to the ground.

Rarely fatal

On the evening of August 8, 2014, Sameer fell ill. He woke up with diarrhea that wouldn’t abate.

Sheila’s mother sold the family’s small hoard of rice for hospital money. They asked for an endorsement letter from the grandstand’s command center, and brought Sameer to a nearby public hospital.

“We always have roughly 20 cases of evacuees coming in for consultation,” said Dr Maribel Felisario, public relations head of the Zamboanga City Medical Center (ZCMC). All patients identified as evacuees receive free services.

At the ZCMC – locally known as General Hospital – Dr Ofelia Dammang diagnosed Sameer with acute gastroenteritis, without dehydration.

According to Dr Soledad Daguio, chief physician, gastroenteritis is rarely a fatal disease. The hospital says that the baby was started on oral rehydration. Laboratory exams were ordered.

Sheila said that the lines were long, and the hospital crowded. Sameer wouldn’t eat, wouldn’t drink, and refused to even breastfeed from his mother. His diarrhea was worse. He was vomiting and pale.

Sheila said she begged the doctors to look at her son and put him on an intravenous feed. The doctors refused, she said, because they supposedly needed to follow processes.

The family was hungry, said Sheila. At 1:30 pm, they left for the grandstand.

‘They were laughing when we left’

Sameer was worse in the evening. The family decided to take him to a hospital again, and were offered the services of an ambulance standing by the grandstand.

Sheila decided to take her son to private institution Brent Hospital.

The family walked into the emergency room at 7 pm.

“They were staring at us when we walked in,” Sheila said. “They asked us who we were. We said we came from the grandstand, that we were internally displaced. They looked at our clothes and told us there were no rooms available, only private rooms that required a down payment of P2,400 (about $60).”

Sheila had only P200 left from the rice money, roughly $4.

She said the hospital administration refused to take the baby, instead demanding that the family pay for the baby’s dextrose and an ambulance to take Sameer back to the ZCMC.

When Sheila said they couldn’t afford even that, they were asked to sign a form declaring they had no funds.

According to a statement to Rappler by Dr Raymond Sator, Brent Hospital Medical Director, emergency patients are treated immediately, regardless of their capacity to pay.

In non-emergency cases requiring admission, patients are asked for a cash advance of P1,500 ($37).

Indigent patients are referred to other hospitals, usually ZCMC.

The doctors, said Sheila, were laughing as she left with her son.

‘Like a toy’

Less than hour since they arrived in Brent, at 7:50 pm, Sheila and her family returned to ZCMC.

The same doctor, Dammang, assessed Sameer and asked for the results of laboratory exams. Sheila followed orders and handed the results to the nurse. According to Sheila, the nurse took the papers, and set them aside.

“To wait for attention would be really false,” Daguio told Rappler, “Because everyone who comes into the ER is given appropriate and timely attention.”

“I said ‘Doc, please put my son on dextrose,’” Sheila recounted. “I touched my son’s feet. They were cold, like ice.”

The nurse, identified by the hospital as Ludwick Lim, is said to have told Sheila to sit by a door.

“I said, ‘Sir, please don’t make my son wait. Please, Doc, have mercy on my son. He’s throwing up, he won’t stop throwing up, and the diarrhea won’t stop.”

Sheila said they were told the doctors would come. Sheila said the family waited 8 hours.

Daguio, the chief physician, has a different retelling of events. Initially, Daguio claimed the family arrived at midnight – the time records say Sameer was officially admitted into the hospital. She later revised the claim, saying that the family indeed arrived at 7:52 pm, but was given immediate attention before the determination Sameer should be admitted.

“It’s not true that the patient was made to wait 8 hours at the emergency room or was told to wait 8 hours before attention was given,” said the chief physician.

“The patient was given the appropriate attention and timely attention from this institution, from this hospital.”

At 3:30 am, when Sameer was seizing, doctors attempted to put Sameer on a dextrose feed.

“They stuck their needles into him, into his wrists and feet and everywhere, pricked him as if he were a toy. It was too late,” Sheila said. “They waited too long.”

Hospital records show that the doctors attempted to intubate Sameer before his death.

Sheila refused. “I didn’t want them to put a tube down my son. He couldn’t even eat Cerelac, how could he manage a tube?”

Sameer died at 4 am, August 10, 2014.

At fault

“There were lapses from the time the mother brought the child to the hospital and then she took the child home again,” said Daguio. “A lot of things could happen at the time, the patient could deteriorate before the mother could bring the patient back to the hospital.”

Gastroenteritis, said Daguio, is a multi-factorial disease. Much could also be done to prevent its inception, even in the appalling conditions of the Enriquez Grandstand.

“They may be staying at the grandstand, but the mother could have found means of keeping the baby clean. She could have boiled the water that she was giving the child, there’s a lot of ways and means to prevent acute gastroenteritis. Even if they were living in such conditions, it could have been prevented,” Daguio said.

Sheila disagrees.

“Where will we get water?” she asked. “It’s dirty here in the grandstand, but Sameer’s father boils all the water we use. He doesn’t drink much water anyway because he’s breastfed. The water in his Cerelac is boiled.”

Once the disease develops, said the doctor, “it should have been easy” to address the problem with oral rehydration. “If she did not bring the child home, perhaps there would have been a better outcome.”

One month after

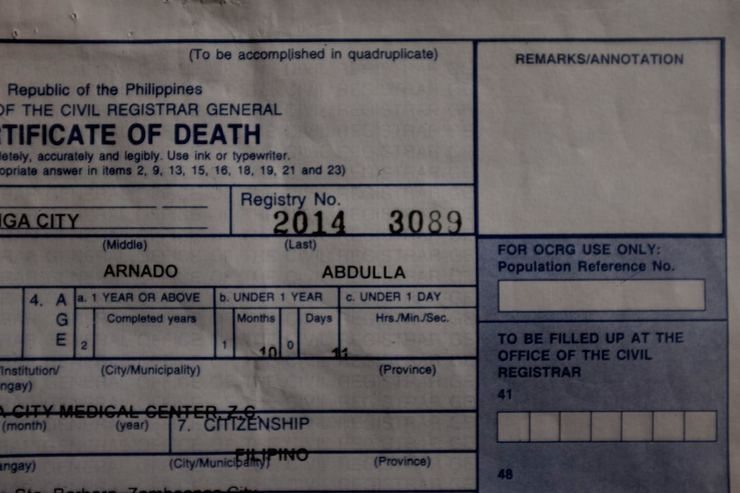

There was no money for Sameer’s burial. Government assistance required a death certificate. In the full day it took his family to do the paperwork, Sameer’s corpse lay in shelter 3J, Zone A, the family’s makeshift space in the grandstand.

Muslim tradition did not allow for Sameer’s body to be left alone in a morgue.

“We slept beside him that night,” said Sheila. “I put my son to sleep beside me.”

Sameer Arnado Abdulla, 10 months and 11 days old, was buried at 3 am of August 11, 2014.

Sheila’s second child Sahil is now feverish and ill with diarrhea.

Zone A of the Enriquez Grandstand, where the Abdulla family now makes its home, has a current total of 4,446 residents. Twenty-one have died since moving into the emergency shelters from a variety of diseases, including dehydration, pneumonia, and cardiac arrest.

Several of the notations kept by the government command center in the grandstand leave blank the cause of death. On August 13, according to the handwritten list, a 65-year-old woman from Santa Catalina died at 3 pm.

The cause of death was marked with a single word. “Complicated.”

Unjustified

The Zamboanga City Health Office now reports a total of 168 recorded deaths among people displaced internally by the 2013 siege, half of them children.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the emergency threshold of deaths for children under age 5 – more than two cases per 10,000 per day – was breached 6 times in 2013.

“We are not very pleased with the number of deaths that is why we have to work very hard to ensure these deaths are diminished,” Zamboanga City Mayor Isabelle Climaco told reporters during an interview in front of the city hall Monday, September 8.

The mayor, however, added that the rising number of post-siege deaths was due to the longer time period.

“In terms of the civilian deaths compared to the siege, it’s because the siege has lasted 28 days and the rehabilitation is lasting more than one year.”

On Tuesday, September 9, 2014, the city of Zamboanga commemorated the year since the siege of Zamboanga.

The next day, September 10, the Abdulla family visited Sameer’s grave with its hand-painted marker, one month after his death. – with research by Joseph Suarez/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.