SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “We had no choice,” said Evelyn Dagotgot, one of the survivors of a fire in Isla Puting Bato that dislocated 5,000 Tondo residents last May.

Evelyn’s destroyed home in Manila was on the breakwater in a “danger zone,” and her family was prohibited from returning to rebuild. Against their better judgment, they accepted the National Housing Authority’s (NHA) relocation offer. They were even shown the home beforehand.

“The site they showed us was not the actual site where we were relocated,” said Evelyn in Filipino. Instead, they ended up in faraway Barangay San Jose, Rodriguez (formerly Montalban), Rizal.

“We wondered why it was next to a river,” said Evelyn.

Several months later, Evelyn was awoken by her neighbor pounding on her door. Unknown to Evelyn, the Wawa dam had overflowed from the Habagat rains.

“There was no no advance warning, not even by megaphone. If our neighbor had not woken us up, we would have had no idea what was going on.” said Evelyn.

“My husband would have no family to return to if we were swept away by the flood,” said Evelyn. “That’s how sad it could have been.”

Geo-hazard zone

Rodriguez lies in a geo-hazard zone. If a 7-9-magnitude earthquake hits, all buildings in the vicinity are expected to collapse. When asked why the NHA selected the site to resettle informal settlers, a staff member of the Municipal Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office noted that the last geo-hazard study was conducted in 2002.

It is not entirely clear who is to blame for selecting a geo-hazard zone as the destination for up to 70,000 resettled informal settlers.

Rodriguez municipal administrator Pascual de Guzman described the role that the municipality plays in the relocation process. “The local government has nothing to do with the choice of relocatees, or with the choice of the developer, the choice of site, it is all the national government.”

De Guzman explained that Rodriguez’s internal revenue cannot keep up with the population increase: “Our budget does not increase just because there are relocatees here – in fact, it burdens us further – because our population – before we became a relocation site – is 70,000 – and after that it doubled.” De Guzman was referring to the population of Rodriguez (formerly Montalban), Rizal before and after the NHA project was built.

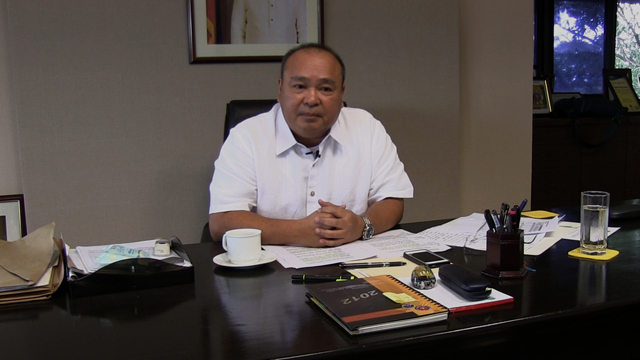

When the issue was raised with the NHA, General Manager Chito Cruz reiterated that a new geo-hazard study was in order. In addition, he noted that the developer was ordered to construct flood-control measures at their own expense.

This may offer little peace of mind to the residents. Evelyn’s father-in-law, Isabelito Dagotgot, is still worried that further flooding may occur.

“The anti-flood walls in Montalban are being repaired but we are not sure if they are strong enough,” said Dagotgot. “That’s why we are worried living in our home in Montalban. If it storms heavily, it will flood heavily again.”

Clearing the danger zones

Evelyn Dagotgot’s relocation is part of an ongoing effort to move informal settlers in Metro Manila out of so-called “danger zones.”

In 2010, President Benigno Aquino III budgeted P50-B to be spent over the course of 5 years on resettling 60,000 informal settlers living in the National Capital Region’s (NCR) “danger zones.”

The NHA hopes to resettle 20,000 informal settlers per year, with a focus on Manila, Quezon City, and Pasay City.

The Five-Year Plan clearly calls for the prioritization of on-site (in-city) – as opposed to off-site (out-of-city) – resettlement.

“They told us that in-city relocation was impossible. But for us, off-site relocation is impossible. The relocation site they offered is dangerous,” said Loida Cillo, board member of the Samahang Magkakapit bahay ng Valderama (SMV) in the Del Pan area, Manila.

Since Loida lives meters from the Pasig River, her home is automatically a “danger zone.” A Supreme Court ruling mandates the clearing of the 3-meter easement along the Pasig River.

However, Loida considers off-site relocation projects to be even more dangerous.

“They can get flooded, like in Montalban,” said Loida. “It is flood prone, and earthquake prone.”

When asked if the P50-B fund could be used to construct on-site housing for informal settlers in Manila, NHA’s Cruz confirmed that this was indeed a priority, but added, “There is not enough land to put up the necessary buildings. The funds are there, but unfortunately there are not enough lands provided by the LGU.”

In a subsequent interview with Rappler, Vicky S. Clavel, Head of Urban Settlements Office, Manila, was clear that the city had no land either: “Land acquisition is not included in the 50 Billion Peso budget,” said Clavel. “The city of Manila has no money for that purpose. In RA7279 it states that the NHA should provide relocation areas” (RA7279 – The Urban Development and Housing act – provides legal protocol for the resettlement of IFS).

“We want the national government to work more closely with the LGU,” said Loida, referring to an apparent disconnect between the two actors. Her organization has been proactive in identifying nine potential sites for constructing on-site housing.

“Our group reviewed potential relocation sites,” said Loida, referring to papers filed with the NHA and partner organizations pinpointing nearby vacant lands. “So if the working group gives the go-ahead, we will have documents proving that we have identified possible relocation sites.”

When asked what the city of Manila could do about the 9 sites proposed by Loida and her neighbors, Clavel said, “There is not yet an effort to negotiate for this property, which has to be done by the NHA. As far as it is concerned, we have no funds for expropriation.”

Clavel said that the community at Del Pan has been relocated before. Said Clavel, “According to the NHA they do not deserve a relocation site but for humanitarian reasons they have provided them a relocation site.”

Loida’s sister, Aurea, confirmed that in the past, money was offered for informal settlers of Del Pan to dismantle their own homes. She pegged the amount paid at P1,500. According to Aurea, those who accepted the money were blacklisted, and may not be eligible for further resettlement assistance.

Another relocation

Meanwhile, the relocation of the Del Pan informal settler community, also in Manila, is imminent.

According to Manila Mayor Alfredo Lim’s chief of staff Chic de Guzman: “We’ve made a consensus with all of the people in Del Pan, and as much as possible we want this to be in a peaceful way. That’s why we have continued dialogue with them, and then they will agree.” Guzman went on to say, “By law, pretty soon they know they are going to be out of there.”

It is unclear how the NHA can prioritize on-site resettlement without a budgetary mechanism to purchase property.

A recent memorandum circular shows that the NHA can tweak their rules so that, with a detailed CSO (Civil Society Organization) or LGU proposal, funds can be allocated to purchase property for on-site construction. In addition, the NHA is tapping currently available lands in Manila to construct around 10,000 units in the Smokey Mountain area.

However, according to the same memorandum circular, “The cost of land, land development and housing construction funded out of National Government funds shall be recovered from the project beneficiaries.”

In other words, NHA housing is not free. Residents pay on long-term mortgages until they own the property. And even then they’re not assured of a good return.

Rodriguez’s example

According to a source privy to the transactions, the construction of the resettlement site in Barangay San Jose in Rodriguez town (formerly Montalban) was outsourced 3 times. Labor costs for each home were, according to the source, only P5,000.

There are holes on two walls of Evelyn’s home, such that families could see into one another’s living spaces. The cement walls are very thin, and the rebar is scarcely thicker than a drinking straw. The toilet door will not stay shut and the windows will not properly close.

Although the value of the house is P175,000.00, Evelyn claims she will be be paying P140,000.00 given the NHA assistance. The houses are free to live in for one year, after which the tenants will be paying a monthly fee of P200.00. Pay will increase thereafter on a yearly basis until the mortgage is entirely paid.

“For now, the house is still free, for one year,” said Evelyn. “But we can’t afford the mortgage plus the water and electricity bills. My husband doesn’t have work here, so I think we will return to Isla Puting Bato.”

And the cycle continues. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.