SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

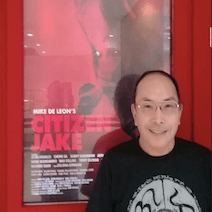

![[OPINION] Hayskul Batch ’73: We were the martial law teenagers](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/57911B07C7704C5993C16F8463D686FA/imho-matial-law-teenages-3.jpg)

(The following is an essay to be read in 2023 on the occasion of the 50th reunion of the author’s high school batch.)

Fifty years ago, 121 boys and 177 girls graduated from high school in a country undergoing tumultuous changes brought about by Martial Law. We were those teenagers and this is our story.

It was a period of unusual anxiety for us – we worried about what the future held for us, what courses to pursue in what colleges and where, if the party we attended would end on time, when we could have our pants sewn in the bell-bottom style of those days, if our baby fat would show in our tube blouses, if the miniskirt was short enough to show off our leggy assets but long enough to pass the prescribed length measured by the rulers of Ma’am or Sister, if we could have those stiff-collared trubenized polo shirts with rounded tails to conceal the embarrassing bulges brought on by our raging hormones, if the shaggy hairdo was shaggy enough or shaggier than the others’, if our crewcuts would grow fast enough so we could look like midget Atoy Cos or Robert Jaworskis.

We faced the usual growing-up problems of teenagers with shaky bravado: how to get rid of unsightly pimples, gain additional inches for our height and/or breast size, lose/gain weight, with whom to dance or who would ask us for a dance during parties, the desperate mission of finding a boy/girlfriend in time for Valentine’s Day, making up alibis for a clandestine romantic date, finding someone who could write love letters for us, trying on perfume/makeup to charm someone.

Those were the dizzying days of hormone-driven puppy love, loss, or the agony of waiting for the right boy or girl to come along, rejection in courtship and frustration from getting courted by a boy while we pined for another, jealousy, theme songs and songs with which to cry our broken hearts along with (copied from the ubiquitous small songhits and Jingle Chordbook magazines).

It was a simple world and life we had then. Our allowance was enough to buy several sticks of banana cue to be shared among friends, a fleeting glimpse of our crush was enough for us to have a natural high, dreams and ambitions were easier to conjure and looked just within our reach. We respected our elders and people in authority no matter what. Like our parents, they were to be trusted to look after our well-being. We trusted our friends, acquaintances, and neighbors.

But when Martial Law was declared in 1972 and changed the dynamics of our relationships; paranoia became the order of the day. And our lives were never the same again.

“Communists,” specifically the Kabataang Makabayan (KM), became the new bogeymen in our collective nightmares. Saying the “wrong” words, doing the “wrong” things, associating with the “wrong” people could land us in the PC Barracks stockade. Boys rushed to the barbers to have their already short hair cut even shorter (white-side wall) after seeing pictures of local male celebrities’ long-hair snopaked in the government-controlled and censored newspapers.

With the print media, radio, and television stations sequestered and controlled by the government, only the good side of Martial Law was shown to us. Being 1,582 kilometers from Metro Manila and with the censored media, we were practically ignorant of the activism and uprisings there.

Our parents often talked about Martial Law in whispers. Our teachers and school officials never talked about it in our presence. One persistent rumor in the early days of Martial Law was that the boys taking the Philippine Military Training (PMT) would be enlisted to fight the “communists.” However, it turned out to be untrue, and instead PMT was replaced by the Citizens’ Army Training (CAT).

Some batchmates, enrolled in a judo-karate club, talked about the janitor who suddenly disappeared. The janitor, later identified as writer-activist Eman Lacaba, was killed by the military years later in Davao del Norte. We would be hearing about skirmishes between the Christian Ilagas and the Muslim Black Shirts and how victory was influenced by their amulets (made of human ashes in small perfume bottles strung around their necks) and their ritual of making the proper steppings (like in a dance choreography) while fighting each other.

On the other hand, we were busy memorizing the “Bagong Lipunan (New Society)” song (May bagong silang, may bago nang buhay, bagong bansa, bagong galaw sa Bagong Lipunan, magbabago ang lahat tungo sa pag-unlad at ating itanghal, Bagong Lipunan!) which was later sung after “Lupang Hinirang” during flag ceremony. Student activism was still in the years ahead of us in this side of Mindanao, which was so far from the metro.

But being teenagers, we had creative ways of dealing with whatever came in the way of our having fun. When people, young and old, men and women, were “invited” to stay overnight in the PC Barracks stockade for violating the 9 pm curfew, we were able to convince some of our parents to host the stay-in house parties (proms were canceled then).

These parties were tame: We danced, talked, ate all night, and went home when the curfew was lifted at 5 am the following day. Later, a general order was issued setting the curfew from 12 midnight to 4 am, but our stay-in parties continued nevertheless. In these parties, the favorite dance song of the boys was The Beatles’ longest 45 rpm single, “Hey Jude” (running time: 7 minutes and 11 seconds) which, of course, was most hated by the girls because their arms grew numb from maintaining their defensive triangular position propped against the boys’ chests. On the other hand, bouncy tunes were accompanied by our frenzied maskipops (maski papaano) dance moves.

Weekends were usually devoted to afternoon group dates to watch movies (double program with two movies for the price of one ticket) at Capitol, State, or Golden City Theaters. We provided each other with alibis for our parents.

Surprisingly, we found drug use uncool, although we were made aware of it by classmates who were transferees from Metro Manila. Yes, we were curious about it, but we never went beyond a few puffs of Maryjane. Mandrax, a sedative, was also common, but we’d rather spend our allowances on food and snacks like banana cue. Also, we were lucky to have eagle-eyed teachers and school officials who also had bloodhound-caliber noses to detect the peculiar smell of marijuana smoke. How they became familiar with its smell was one question that remained unasked.

The Marist Brothers and Dominican Sisters ruled over us with firm but benevolent hands. In those turbulent times, while our parents worried about the near future, they were our anchors who made sure that we said our rosaries and attended the 7 am Sunday mass. Many of us remain prayerful to this day.

The fierce competition we faced from the rival school contingent only brought us closer together, especially in interschool competitions and meets. Scores not settled in these contests were quickly decided through fisticuffs in the cogon-choked areas of the vacant lot in front of the school, or in the banana plantation in Dadiangas Heights.

As we eagerly awaited our College Entrance Test (CET) results, we discussed what college course we wanted to take in what university while taking sips of our Coca Cola/TruOrange/Lem-O-Lime or chewing Tarzan/Chiclets. Those of us who would be left behind envied those who would eventually be sent by their parents to college in Metro Manila, Cebu, and Davao. Promises were exchanged that letters and pictures would be sent to each other. We totally avoided talking about our impending separation after high school graduation.

Graduation day at the Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage Parish Church was a simple affair which started with a mass, punctuated by our singing of the splendid hymns composed by Sister Anunciata, SPC. The singing practice was well-attended weeks earlier because of the opportunities it presented to us to make a last-minute/ditch flirtation with each other across the aisles that separated us.

As we sang our graduation song, “We Owe the World a Song,” we became misty-eyed at the thought of our inevitable separation, of the final moments of our high school life, of the beginning of a new phase in our lives under the New Society, the euphemism given to Martial Law. Yes, we were “lucky” to have been teenagers during the early years of Martial Law, and as we went to college, we saw the horrors and evils of the New Society and the military abuses. We have relatives, friends, and schoolmates who were caught and killed in the crossfire between the military and the rebels, became victims of abuse and torture, and disappeared without a trace. Martial Law indeed left an indelible mark in our lives as its survivors.

Fifty years later, here we are – together again. We survived Martial Law! We are given this chance of renewing our ties, re-bonding our friendships, reminiscing about our high school life, laughing over “serious” matters that we now consider as trivial, crying for our classmates who had gone ahead and whom we sorely miss, being grateful for the lives we are leading now and for the impact our teachers and school officials had on us, finding opportunities to be of help to those batchmates whom we believe can use a helping hand, and rallying behind our alma maters.

We were the Martial Law teenagers and this is our shared history. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.