SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I arrived in Basco airport, the capital of Batanes, just after the crack of dawn on what looked like a stormy day. Gray clouds hovered overhead while sheets of rain intermittently poured down on the tarmac. It was, by all accounts, not exactly the picturesque welcome one would for hope upon reaching what has increasingly become the Philippines’ ‘it’ travel destination.

I arrived in Basco airport, the capital of Batanes, just after the crack of dawn on what looked like a stormy day. Gray clouds hovered overhead while sheets of rain intermittently poured down on the tarmac. It was, by all accounts, not exactly the picturesque welcome one would for hope upon reaching what has increasingly become the Philippines’ ‘it’ travel destination.

The tiny archipelagic province of Batanes – its total land area of around 219 square kilometres makes it the smallest one in the Philippines – is geographically closer to Taiwan than to mainland Luzon. Its famous terrain, characterized by limestone cliffs and rolling green hills dotted with grazing cows, has moved travellers to compare it to dramatic landscapes found in New Zealand or Ireland.

Suffice it to say, I was not in Batanes for the tourist circuit. Together with a Rappler video crew, we were there as part of Rappler’s partnership with Oxfam in the Philippines to document stories to increase public awareness about the worsening impacts of climate change, particularly on the poorest and most vulnerable Filipinos.

After all, behind the postcard-perfect images of Batanes live a people, who continue to be on the frontline of the battle against climate change, having recently survived the onslaught of super typhoon Ferdie (international name: Meranti), the world’s most intense storm in 2016.

Typhoon-battered province

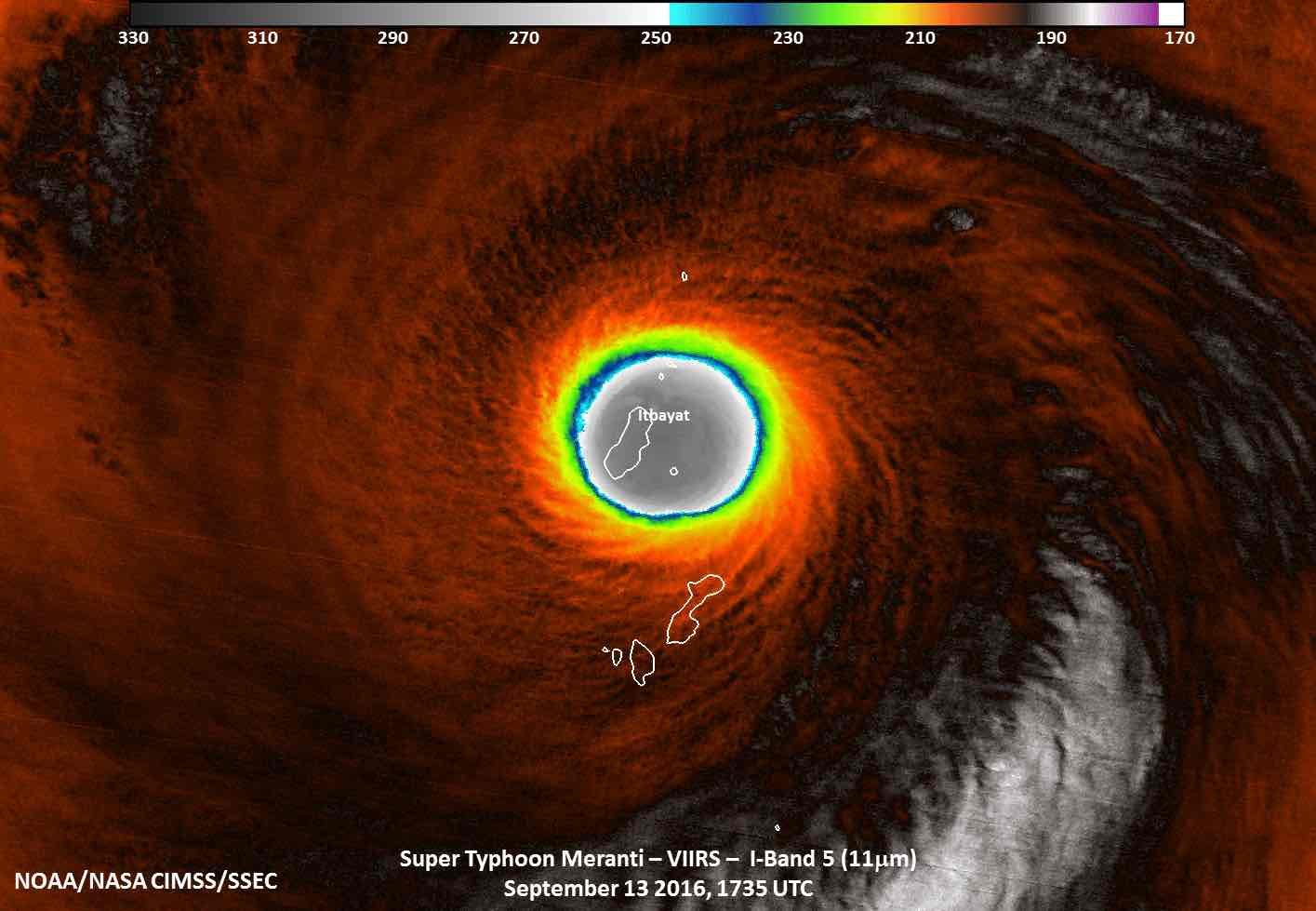

As the weather cleared that day in Basco, hours after we arrived, we boarded a 5-seater Beechcraft plane that would take us to Itbayat, Batanes’ northernmost inhabited island, where typhoon Ferdie first made landfall on September 14, 2016. Notably, Itbayat gained international fame after a satellite image from CIMSS, which showed it right in the eye of the typhoon Ferdie, was published by numerous global news media organisations.

In Itbayat, we met Mrs Faustina Cano, our host and an indigenous Ivatan elder, who is fondly known around town as Nanang Tinang. Before letting us set out to start filming, she delivered a short lecture about her beloved hometown, something she likes to do with all her guests, being a retired high school Araling Panlipunan (Social Studies) teacher.

Nanang Tinang, 75, explained that due to Batanes’ location in the fold of the Pacific Ocean and the West Philippine Sea, it is extremely vulnerable to typhoons. Over the centuries, the indigenous Ivatan people have adapted to this harsh environment by, among other practices, building one-story vernacular houses made of stone, lime and cogon that are meant to withstand strong winds and heavy rains.

Over the last decade, however, the famously resilient Ivatan homes have proved defenseless against the increasing severity and frequency of typhoons hitting Batanes and the rest of the Philippines, again named one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world in 2016.

“Dito sa Batanes, sanay na kami sa bagyo. Bahagi na ito ng buhay namin, kaya ang paghahanda sa bagyo ay isang mahalagang bahagi din ng kultura namin,” said Nanang Tinang.

“Pero kahit sanay na kami, nakikita ko na palakas nang palakas ang mga bagyong dumadaan sa amin. Hindi na namin ma-predict ang panahon ngayon, at kahit kami nagulat sa lakas ng typhoon Ferdie – never ko naranasan sa buong buhay ko ang ganun kalakas na bagyo,” she said.

(Here in Batanes, we are used to typhoons. It is part of our life, and so preparing for storms is also an important part of our culture. But even if we’re used to typhoons, even I have noticed how much stronger they’ve been getting. We can no longer predict the weather these days, and even we were shocked by typhoon Ferdie’s strength – I have never in my entire life experienced a storm that strong.)

Mr Sabas De Sagon, acting mayor of Itbayat, whom we later met at the municipal hall, agreed: “Iba na talaga ngayon. Marami dito ang nagsasabing hindi na nila mabasa ang panahon. Kapag umulan, sobra ang buhos, kaya maliliit ang butil ng bawang. Kapag tag-araw, sobrang init, nakakapaso sa balat kapag nagsasaka.”

(It really is different now. Many farmers here say they can no longer predict the weather. If it rains, it pours so heavily that our garlic bulbs have become smaller. During the summer, it’s gotten too hot to go out and farm.)

Rebuilding after Ferdie

Most local residents like Nanang Tinang have since constructed modern concrete houses. But many of the poorest communities, such as barangay Yawran in Itbayat, still use vernacular houses or simple huts made out of wood and cogon. Not surprisingly, it was those communities that were damaged the most by typhoon Ferdie.

In Yawran, we met Clara Magasing, 28, and her three children, who were resting inside the new hut they had built with the help of their neighbours. Their old house was blown away by typhoon Ferdie.

“Dito sa amin, dapa lahat. Lumabas kami ng bahay bago ‘to tinangay ng hangin. Yung dalawa kong anak, pinasok ko sila sa orocan malapit sa pader, niyakap ko yung orocan at nagtago sa pader. Yung mga kapitbahay ko, humawak sa mga puno para hindi sila itangay,” recalled Clara.

(Here, everything was destroyed. We went out of our house just before it was blown away by the wind. My two children, I made them hide inside an orocan close to the concrete wall. I embraced the orocan and hid behind the wall. My neighbours were hanging on to trees so they wouldn’t get blown away.)

Despite such harrowing accounts, there were no deaths in Batanes from typhoon Ferdie, even in barangay Yawran. The total damage caused by the typhoon, amounting to Php835-million (US$16.6-million), was limited to houses and infrastructure, as well as agricultural crops, especially garlic, the main source of cash income for most farming families in Batanes.

According to acting mayor de Sagon, the experience of the Magasing family and others in Yawran sparked discussions about how people in Itbayat can ensure that everyone, especially the poorest in their community, is prepared and protected during typhoons and other extreme weather events.

“Sanay man kami sa bagyo, ngayon na andito na nga itong sinasabi nilang climate change, kailangan mas galingan pa naming ang paghahanda. Pero kailangan din namin ng suporta lalo na sa national government, lalo na sa paghahanap ng masmainam na livelihood para sa mga mahihirap na pamilya,” he said.

(Even though we are used to typhoons, now that climate change is here, we need to improve our preparedness. But we also need the support of the national government, especially in finding livelihoods for poor families.)

Another town, another typhoon?

As I reflected on stories we heard in Yawran and Itbayat, I feared that these may not necessarily be new to Filipinos – even if it’s Batanes, it’s just another town hit by yet another typhoon. Aren’t we so used to hearing about disasters that, unless it’s on the scale of super typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan), it barely feels like news anymore?

Climate change campaigners might agree that one of the challenges in communicating the human impacts of climate change involves reaching those have been desensitized by all the news, as well as engaging audiences outside what I would call ‘climate circles’ or people who are already interested in, or working on, climate change issues. (READ: Duterte signs Paris climate deal)

Perhaps, by using virtual reality technology, as we sought to do with Rappler in Batanes, we can revive people’s interest in the subject, and increase their willingness to empathize with those affected (as touted by many communication leaders, such as in this TED talk). But whether or not this will be the case is not the main goal.

Rather, it is to show Batanes in a different light: less glossy than in travel magazines yet less desperate than in weather reports; a real place where people, who are least responsible for, yet are most badly affected by, climate change impacts, continue to live and work, seeking national and global support to confront what is indisputably one of the greatest challenges of our time. – Rappler.com

*Airah Cadiogan was the Climate Policy and Campaigns Officer for Oxfam in the Philippines. She is now with Oxfam GB as a Global Campaigner for Food and Climate Justice.

YOU can help raise the voice of people in Itbayat, Batanes and other climate-vulnerable areas by urging the Philippine government to uphold and implement the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and prioritize funding for climate change adaptation initiatives.

Sign the petition: https://act.oxfam.org/asia/philippines-ratify

*US$1=Php50.29

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.