SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Relearning the Spanish language will tell us more about our history](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/12/relearning-spanish-history-December-9-2020.jpg)

There is a growing consensus that this year can only be described as WTF, what with CoviDu30. But all is not dreary, for there is reason for celebration next year, at least in the Philippines. Come March 16, 2021, it will have been 500 years since Magellan and crew spotted Philippine shores (they made their first landing on March 17, 1521). The significance of this event cannot be overstated enough. Thanks to this accidental arrival, a collection of disparate communities and kingdoms were put under the single banner of the Spanish crown, and hence, the Philippines was born.

I say accidental because records and archives show that Magellan’s main mission was to locate Moluccas, the famed Spice Islands, via a westward route that would allow Spain to bypass the limitations set by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Nowhere was “discover an archipelago and have yourself killed by a man whose name repeats” listed in their instructional. Even the name of the fleet, Armada de Molucca, makes the voyage’s intention unambiguously clear.

Since that chance coming, up to the tail-end of the 19th century, Spain had largely defined Filipino culture. That’s 3 centuries worth of history: 300 years of Spanish education, music, fashion, architecture, science, cuisine, gastronomy, art, etc.

But it’s a history that is mostly neglected by Philippine posterity because it is recorded in a language that Filipinos keep on denying and denouncing. The court of nationalist pathos has condemned Magellan and his crew as the harbinger of western corruption, bringing waves of death and decay to precolonial Philippine cultures. And ever since that judgment, the Spanish language has languished in disregard and rejection.

It didn’t help that the Spaniards were quite keen to annoy the locals right after they found steady footing in the Philippines. Eager to explore their imperial potential, they immediately went around the archipelago and subjugated the populace, abused the women, exploited natural resources, and ended their days in prayer. Mysterious indeed are the ways of salvation.

But the outright rejection of the Spanish language just because it was imposed by an imperialist power is consequently a repudiation of a significant part of Philippine history. For most of its existence as a formalized geographic and political entity, the Philippines adopted the Spanish tongue for various uses and even integrated it into the many Filipino vernaculars. That’s why there are remnants of Spanish in modern Philippine languages: for the Christian majority, they still direct their highest devotion to Diyos; for many regardless of religion, they still express their rawest emotions by mentioning a Spanish canine mother. To reject Spanish is therefore to silence the voices of our forebears who spoke, repented, prayed, sang, cursed, joked, and complained in Spanish.

Unless we want to recover this neglected chapter in our history, then we should consider a comprehensive concerted effort to relearn the language that once echoed throughout the archipelago. The radical reintroduction of Spanish in formal education and popular use isn’t impossible; we just need that initial impetus.

We have much to gain from this undertaking. I say “we” because I have a personal stake in this issue. As a biologist, I’m interested in precolonial Philippine folk knowledge about the natural world. As a historian, I’m interested in the intellectual traffic between east and west. One study has found an interesting confluence of the two fields. The Jesuit scholar George Joseph Kamel compiled the first materia medica catalogue of native plants in the country and also established the first “modern” pharmacy in the Philippines in the 17th century. Kamel’s medical approach was a synthesis of his western education and his adept appreciation of local botanical novelty. He categorized the unique healing properties of Philippine flora within the humoral system and sent back his findings to Europe. His project shows that intellectual traffic went in both directions, that the Philippines wasn’t just a passive receptor of foreign science but also an active participant in its global growth.

As part of the international network of scholars called the respublica litteraria, Kamel didn’t exclusively write in Spanish. His letters to his European colleagues were mostly in Latin, the intellectual language of his time. But while this may instead lend to the argument that we should learn Latin (we should because Rome is forever, imperium sine fine), Kamel’s example highlights two important points about the importance of relearning Spanish: the Philippines was welcomed into the global community of scholarship (albeit brutally) via Spanish colonization and relearning Spanish might reveal more about this development.

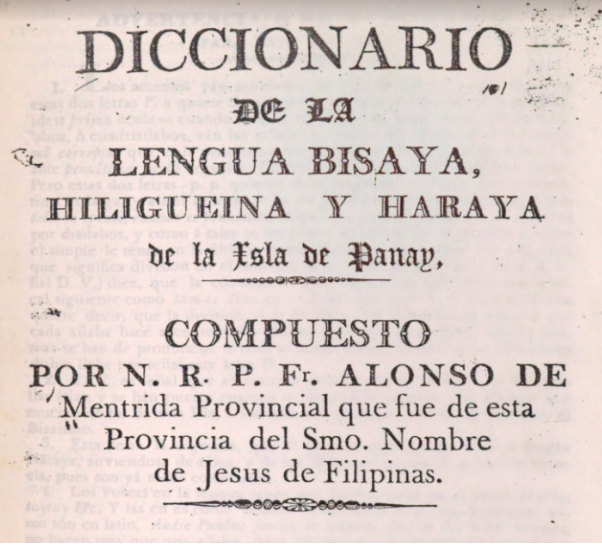

It cannot be denied that a lot of Filipino natives suffered under Spanish rule, but it also cannot be denied that a number of Spaniards struggled for the betterment of Filipinos. As early as 1582, the first bishop of Manila, Domingo de Salazar, sent back word to the king in Spain that his appointed officials in the Philippines were treating the locals cruelly. Many of those who settled in the Philippines also devoted time and energy to study local languages and cultures. What is considered to be the first Hiligaynon dictionary, Bocabulario de lengua bisaya, hiligueyna y Haraya de la isla de Panay y Sugus y para las demas islas, was written by the friar Alonso de Méntrida in 1632.

One of the first historical accounts focusing on my island, Negros, was also in Spanish. In 1881, the Spanish lawyer Robustiano Echauz was appointed judge of the Court of First Instance in Bacolod. He occupied this office for 4 years and was then transferred to Manila in 1885. During his stay in Negros, he went around the island and meticulously took notes that ranged from descriptions of rivers, chickens, mountains, local ritual practices, city administration, sale of agricultural land. He published his findings and observations in a short text called Apuntes de la isla de Negros in 1894.

For a more general survey of the archipelago, Antonio de Morga’s Sucesos de las islas Filipinas is still a historical treasury waiting to be further studied and scrutinized. When Jose Rizal read a copy of the Sucesos in the British Library two centuries after it had been published, the Filipino scholar found it wrought with prejudices that he undertook a serious footnoting project to correct and criticize some of Morga’s assertions. This was possible because Rizal was extremely proficient in Spanish.

There are a lot more related texts in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain that await devoted scholarship and research. Other works are scattered all over the world, be it in libraries or in private collections. Relearning Spanish is one of the first steps that Filipino historians can take in order to fully understand the secrets they hold. Because most of these recount Philippine history as merely an extension of Spanish history in the Pacific, they are direly in need of rectification by researchers and historians willing to extract from them a unique history of the Philippines.

Before arriving in the Philippines, Magellan and crew suffered disease and starvation for months in the Pacific Ocean. Learning a language might be peaceful now with apps and online lessons readily available, but it’s the dreary length of time spent studying that is punishing. But if we only persevere like Magellan and crew did, we might find new realms of knowledge awaiting our arrival. – Rappler.com

Pippo Carmona is a Filipino biologist and historian of medicine. He writes about ancient Greek and Roman medicine in his blog The Panacea.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Rethinking monuments](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/07/monuments-640.jpg?fit=449%2C360)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.