SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Well-being, economics, and measuring what really matters](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/11/wellbeing-november-2-2020.jpg)

Since President Diosdado Macapagal’s economic liberalization policy, there has not been a drastic change in the way we conduct economic policy in the Philippines. The pursuit for economic efficiency and growth has always been at the core of each administration’s governance agenda. Perhaps that’s a good thing. Or maybe not.

We owe the relative stability of economic policies to the outstanding theoretical and empirical advances in Economic Sciences in the 20th century, especially after the Great Depression in the 1930’s. Since then, economists have developed models which allowed us to understand how people and institutions behave, how they make choices, how market forces interact, and so on. Mathematics has since been foundational to sound economic theory to ensure logical precision. And because these models are mathematically precise, they carry with them a significant degree of stability and consistency when applied to policy. Isn’t that great? Well, only to a certain extent.

Without dropping Greek letters and equations, let us try to look at one economic model called the standard model. The standard model is considered as the basic workhorse used in the analysis of public policy. Like all models, it has assumptions: (1) we want more to less; (2) we have consistent and relatively stable preferences; and (3) given the constraints we confront, we make decisions to make ourselves better. Reasonable and realistic? Looks like it.

The model is analytically powerful. It allows us to make empirical estimates and predictions to inform policy. We can think of how an increase in market prices due to added regulations will affect consumer behaviour, i.e. will they be better off or worse off with the change? We can model how a reduction in income taxes and the consequent increase in disposable income affect the consumption and savings of households. In optimal tax design, we can simulate the effect of varying amounts of excise tax on cigarettes and estimate the differential effects on consumption across income levels.

In all these examples, one link is clear: the relationship between prices and our “well-being.” And this relationship provides the basis for all rigorous empirical exercises being used in policymaking such as the national income accounting (e.g. GDP) and the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA) as the basis for policy decisions.

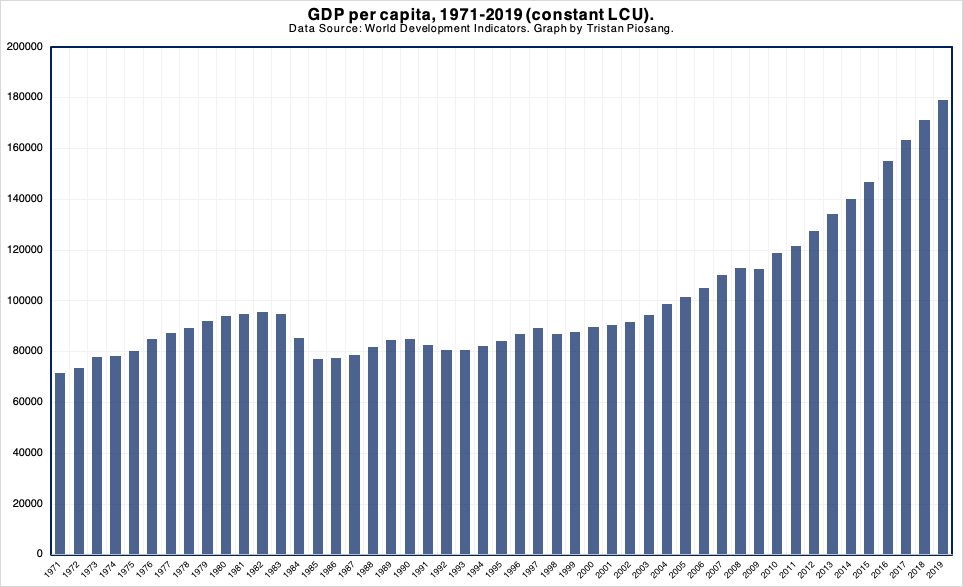

Let’s take a closer look at Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – a measure of all income generated in the economy. The graph below shows the real GDP per person in the population, considered as a rough measure of living standards, from 1971-2019. For our purpose, this GDP construction is more meaningful since it accounts for changes in population and price levels (i.e. inflation) overtime. The graph tells us many things, but I wish to highlight two. First, with the exception of some periods like in 1982-1986, the general trend is that our living standards is increasing overtime. Second, in 2019 the rough estimate of each one’s living standards is P179,144.6.

But how do these numbers fare in reality? One does not need to crunch poverty and income inequality data to realize that macroeconomic accounting does a poor job in representing the improvement (or the lack thereof) of the lives of most people. One only needs to walk around Manila. Yet the tendency is to frame these numbers as the be-all and end-all indicators of governance success. For so long, whether we admit it or not, we are fixated with economic growth and economic growth alone. It is that propensity that creates the tension between the rigid numbers we measure and the complex reality of people’s lives around us. Then we realize that the numbers seem to not reflect “reality.”

But don’t get me wrong. Nobody is saying that GDP is not important. To get the macroeconomy right is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for public policy. But we should be clear on one thing: GDP should not be projected as a measure of people’s well-being, and therefore should not be projected as the principal indicator of governance success. Kuznets, who invented the measure, was very clear about that.

Then what’s the fuss all about?

For those of us concerned about measurements and quantification for the improvement of whatever social welfare function, perhaps it is time to ask ourselves: are we measuring all that really matters to most people? Do our models capture all variables that matter to most people?

Take Manila as a live case. It has something that we “want” for the countryside — economic vibrancy. Growth. But with the physical environment that the vibrant economy has created for the region, how do you think does that affect people’s well-being?

In Europe and New Zealand, more and more economists and public policy practitioners are being kept awake at night by these questions on the Economics of Wellbeing. Since the 2009 publication of the report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress by outstanding economists Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, the agenda has been slowly but surely refocusing towards understanding well-being and its place and value in public policy and the economy. And there is nothing really fancy about it. We use the same econometrics, same empirical tests. But the fundamental difference is the central question of analysis which we draw from the work of Sen:

What should we do to enable people to lead the kind of lives they value and have reason to value?

In the Philippines, the SWS and economist Dr Mahar Mangahas started working on quality of life measurements since 1985. But the extent to which policymakers use their data in the design and analysis of policies is the million-dollar question.

In advocating the refocusing of policy away from myopic measures like GDP, our aim as accurately put by the British economist Gus O’Donnell “is to be roughly right, not precisely wrong.” – Rappler.com

Tristan Piosang is currently a master’s student in Public Policy and Economics at the Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. He is a recipient of the New Zealand Development Scholarships Award by the New Zealand Government. He is working on Well-being Economics for his master’s research work under the supervision of Prof Arthur Grimes.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] 5 ways Duterte is derailing PH economy’s recovery](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/10/TL-duterte-derailing-econ-recovery-October-23-2020.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.