SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Why do disasters happen? Debunking common misconceptions](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/06/imho-disasters-1280.jpg)

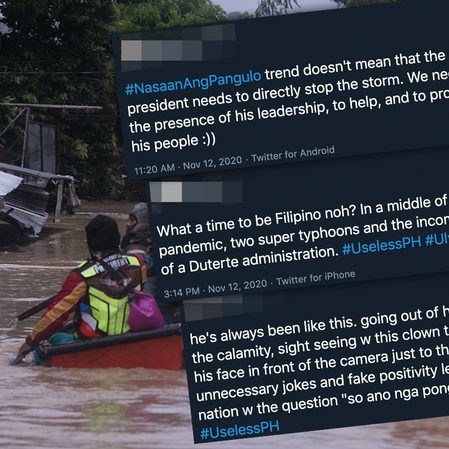

We often hear the term “natural disasters” – referring to how a natural phenomenon causes a disaster. But this commonly used phrase is a fallacy, a misconceived notion that presumes disasters as naturally occurring.

Contrary to that perception, it is time to recognize that there is no such thing as a natural disaster, only natural hazards. This is also the long-time campaign and advocacy of the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR). The UNISDR emphasizes how anthropogenic causes, unplanned urbanization, unchecked poverty, destruction of the environment, and the lack of international cooperation are among the drivers of the increasing intensity and frequency of disaster events.

A dilemma of language

However, the term “natural disaster” is still widely used among politicians, media organizations, civil society groups, and international organizations – and, more surprisingly, among scientists and disaster risk reduction (DRR) practitioners.

In a study, Chmutina and Von Medding (2019) systematically analyzed the use of this expression and saw how the term disconnected from the reality of the most vulnerable by putting the blame on “nature,” putting the responsibility for failures of development on natural phenomena or “acts of God.” The study said the term was initially used in the 1990s as a way to leverage popularity – with no communication agenda – to trigger particular associations and behaviors among the public. However, this resulted in negative impacts and misconceptions about disasters.

Disasters and hazards

At present, a disaster is defined as a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic, or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources (Philippine DRRM Act of 2010). To put it simply, disasters happen when: (1) there’s a hazard – either natural or human-induced; (2) there are losses and damages associated to the levels of exposure and aspects of vulnerability; and (3) the lack of capacity to deal with the impacts of the hazards.

So are all hazards a disaster? The answer is NO. Disasters are no longer viewed as the function of physical hazards.

A hazard is a dangerous phenomenon or a threat – slow onset or onset – which can only become a disaster if there are losses and damages, and if the community can no longer deal with its impact.

Imagine a community living in a coastal area with risks of storm surge, but that was able to preemptively evacuate to safe areas and secure its members’ livelihoods. Imagine the community being informed on what to do before, during, and after a tropical cyclone. Imagine the community and the local government leading family preparedness planning and implementing the preparedness measures in times of a tropical cyclone. Imagine infrastructure built to mitigate impacts of flooding and storm surges. These are only a few factors that can reduce the risks of a disaster and, most importantly, prevent loss of life.

Disasters are not a by-product of a single factor. They are usually the result of an interaction between systems within systems.

Predicting disasters

So can we predict disasters? Maybe.

Given all the technology we have right now, DRR practitioners can now assess hazards and risks in areas even without the hazard actually happening. In a single click, you can generate knowledge on the hazards in your community, understand the associated risks, and most importantly, prompt disaster preparedness actions. Apart from these hazard assessment tools, there are also applications which can generate levels of exposure and vulnerability of communities.

But what is missing in the current system is the ability to generate future scenarios, taking into consideration the hastening impacts of climate change, rapid urbanization, and even lack of preparedness. Bridging this gap will avoid the “element of surprise” in disaster events. According to UNISDR (2013), historical disaster data can explain the past but cannot provide a good guide for the future. Most disasters that could happen have not happened yet. Hence, the need for probabilistic risk assessment simulating future disasters based on scientific data.

As a practitioner myself, if the time comes that we can accurately predict disasters, it only means that we have already found a way to prevent them from happening. Disasters are not only about the physical science; what is interesting about them is that there is a social component to them, and an interplay of various systems.

Given the risk profile of the Philippines, our main goal is to build disaster resilience, and the pathway to resilience is reducing disaster risks. Hence, it is critical to grasp that the root causes of disasters are not only natural, and that there is a difference between disasters and hazards.

By setting the parameters on why disasters happen, we help shape the public perception of risks associated with natural hazards. Consequently, we can encourage the public to turn disaster science into action. – Rappler.com

Rachelle Anne L. Miranda is a disaster risk reduction (DRR) practitioner and has devoted her professional life to being a public servant in the Office of Civil Defense. She holds a master’s degree in Disaster Risk and Resilience from Ateneo De Manila University and is currently a master’s candidate in Master in Public Administration Major in Health Emergency and Disaster Management at Bicol University.

Rachelle strongly advocates for a systems thinking approach in building disaster resilience. She is also passionate about DRR capacity building through community preparedness, information, education, and advocacy.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Filipinos aren’t so much resilient as Duterte is incompetent, abusive](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/11/Disaster-Resilience-November-13-2020.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[ANALYSIS] Lessons in resilience from Japan’s New Year’s Day earthquake](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/TL-japan-earthquake-warning-system-jan-3-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Edgewise] Preface to ‘A Fortunate Country,’ a social idealist novel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/a-fortunate-country-february-8-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.