SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[FIRST PERSON] Diary of an anesthesiologist on the frontline](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/04/essay-of-frontliner-sq.jpg)

The date is August 10, 2020.

Earlier this year, I returned to my home country from a research fellowship abroad right at the start of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Despite the developing pandemic, I looked forward to another year of fellowship training, and while waiting for approvals to go through, I preoccupied myself with other things, such as attending driving school, completing an English proficiency exam, and working on a job application.

I was really looking forward to all the exciting plans that I had, but the rising COVID-19 cases outside China caught up with my country, the Philippines. The day I was to get on a bus ride for a job in a different province was the same day my city, Metro Manila, went into lockdown and strict community quarantine. Nobody was allowed to enter or leave.

If there is one constant since the beginning of this viral outbreak, it would be that of change – of plans, of rules, of the way people are. Change is the new norm.

Before I left for my international research fellowship, I was working regularly at various hospitals as an anesthesiologist while studying for my specialty board exams. My work mainly consisted of providing anesthetic care for emergent and elective cases and delivering continuity of this care into and during the postoperative recovery period. I also tended to ward calls for difficult intravenous insertions, emergency intubations, and pain management.

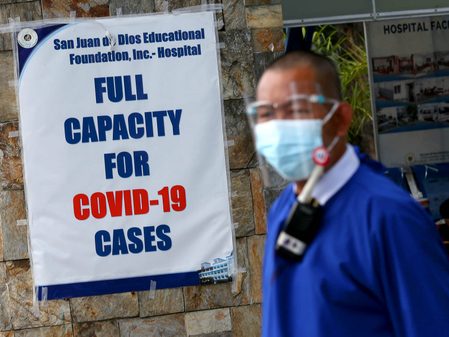

For the past few months, my main job has been intubating patients at the emergency room dedicated for COVID-19 suspected and confirmed cases. These recent weeks have been especially grueling. Several times a day, I find myself having to place a tube down patients’ throats to help move oxygen in and out of their lungs.

A coworker once told me that what I do is the most dangerous procedure a doctor could perform at a time like this. I say, if it prevents greater COVID-19 exposure for doctors and other medical staff who are less adept than an anesthesiologist at intubations, I would rather anesthesiologists like myself perform this procedure. For myself as an anesthesiologist, knowing that I could perform intubations efficiently is the main motivating factor for me to continue performing them as often as I am able to.

In fact, I volunteered my services willingly as the pandemic began to overwhelm the healthcare system. As healthcare workers began contracting the virus, the government put out a call to the medical community to volunteer to help fight the COVID-19 battle. It was my choice to step into the frontline.

Now on my fourth month as a volunteer anesthesiologist, I have developed a new routine to continue to fight the virus while doing my best to keep my family safe. Staying at a site close to the hospital, I am away from my family most of the week and come home a few weekends to take care of my elderly parents’ errands. My parents have health issues, so I try to limit my interaction with them. I take a shower before driving home and isolate myself in my room for the majority of my stay at home.

As anesthesiologists, we are trained to stay calm during stressful situations. “Grace under pressure,” so the saying goes. My training has helped me adapt to the rapidly changing situation as we have had to modify how we did things that used to be routine to us.

Before entering the emergency room, I don protective gear consisting of a coverall suit, a pair of shoe covers, two pairs of gloves, an N95 mask followed by a surgical mask, a head cover, and a face shield. As soon as the mechanical ventilator is set up, there is no time to perform proper preoxygenation. These patients are often incoherent and gasping for air. Some are running so low on oxygen that the cardiac monitor cannot read their oxygen level. I sedate the patient and follow this up with a high-dose nondepolarizing muscle relaxant to paralyze the patients faster. Given the limited availability of resources, I do mostly direct laryngoscopy to visualize the vocal cords. I pass a tube in between them, inflate the cuff while covering the tube’s opening, and then quickly hook it to the mechanical ventilator. I no longer auscultate the lungs to check for tube placement. Sometimes when I feel that the patient is at risk of difficult intubation, I call another anesthesiologist, who brings down the video laryngoscope to help. I learned that early intubations combined with a successful first pass attempt greatly increases a patient’s odds of survival.

When I intubate a patient, I focus so much on making sure I place the tube through the trachea that I often forget the ways the virus could infect me. When you open a patient’s mouth to put a tube in, they can cough, and every time they do, the virus is released into the air. The virus can remain viable floating in the air for many hours, so we perform our intubations in a negative pressure isolation room. These days however, due to the rapid increase in cases, we aren’t getting through patients fast enough and I’ve had to intubate even outside the dedicated isolation room.

Once the patient’s oxygen saturation starts to go up and is more stable, I order a bolus of sedative before starting a continuous infusion, because I worry about the patient waking up feeling uncomfortable and terrified about being paralyzed with a tube inside of them. This is the least I could do for someone who would not be able to see their family for the duration of their admission. That is what the virus does – it separates loved ones.

When I’m not in the emergency room, I cover shifts releasing SARS-COV-2 test results to people whether in person or by phone. These days, specialists like myself do work that may not be related to our specialty due to the dwindling number of available or willing healthcare workers. Even though this part of my job is not anesthesia-related, I’m used to communicating with patients before surgeries to calm them or make them feel more comfortable. Many people who come to the hospital are either angry or confused and I learned how important communication is, now more than ever.

Disclosing the results to patients is more than just telling them if they have the virus or not. Disclosing and discussing SARS-COV-2 results is about giving joy to parents who have not held their children for weeks due to self-quarantine protocols. It is about preventing an individually-run sari-sari store from closing because of the stigma of the owner possibly having COVID. It is about being empathetic towards patients who have tested positive and helping them cope with the news first and then guiding them to recovery. It is about enabling an overseas Filipino worker to get on a plane to Hong Kong to meet her employer who she has given care for for more than 10 years. It is about making sure that a young man could get on a boat to a different island to bury his brother right before the recently reinstated lockdown.

I learned that the best way to cope with the grueling long hours tending to seemingly unending cases is to remember all these people who we have helped and all the people who continue to support us. We HEAL as ONE.

At the time of this writing, the Philippines is experiencing an alarming rise in COVID-19 cases. Today has been so busy that it is only when they played the national anthem via the PA system that I was able to pause and catch my breath.

At the end of the day, despite the exhaustion and disheartenment I’ve faced, I am grateful for how these experiences have renewed my sense of purpose as a physician. I am really looking forward to the time when the pandemic will finally be over, but for now, the sense that I am doing everything I can to help others and save lives is keeping me going. – Rappler.com

Corinna Ongaigui is a board-certified anesthesiologist. She graduated from the UST Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, finished her anesthesiology residency training at East Avenue Medical Center, Quezon City, and completed her research fellowship at Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. After a 6-month stint as a We Heal as One volunteer at the Lung Center of the Philippines, she moved to Bicol (with her ginger cat, Harry!) to extend her services there.

Voices features opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Edgewise] Preface to ‘A Fortunate Country,’ a social idealist novel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/a-fortunate-country-february-8-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.