SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Paano naman kami: Decades of fighting for Palawan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/03/decades-defending-palawan-March-17-2021.jpg)

On Sundays, when our mornings were not lost to swimming training and our afternoons free of homework, we would drive to Honda Bay in Santa Lourdes. Tatay worked in a local nonprofit then which helped establish a cooperative of boatmen and locals to develop Honda Bay into what it is now. Honda Bay is a dock that offers boat services as entry to different islands nearby.

At that time, Pambato Reef was just being developed, and this was where we always went while Tatay facilitated assessment and monitoring of the area. Pambato would later be established as a marine protected area.

We could tell, even before the boat engine quieted down and slowed to a stop, that we were at Pambato Reef, because the water had cleared up. It was almost like there wasn’t water at all and we could see right through – the vibrant corals, the varieties of fish swimming around, a jellyfish or two that we would remind ourselves to avoid, some starfish, the famous giant taklobo shell; it was a feast for the eyes. We would stay in the waters until we were told it was time to go, and then beg for another five minutes, and another, and another. When our boatman fired up the engine, we knew we couldn’t beg longer. Pambato Reef was our playground, and we couldn’t stop playing.

It was in Pambato where I first saw a clownfish. Finding Nemo had just hit cinemas then, but I already had personal relationships with the fish in it. I had followed a striped fish once and when I came up for air, Tatay had also emerged from the water and shouted, Moorish idol! pointing at the fish I was swimming after. He would later tell me that while it is an edible fish, locals avoid it because it’s all bones and no meat. It was in Pambato where I learned that I shouldn’t step on sea urchins and that I should never, under any circumstance, stand on or make my fins touch the corals.

I thought of Pambato Reef when I was in Panglao, during the last week of my 3-month volunteer program in Bohol, where I worked with a nonprofit involved in Carood watershed conservation. The corals were nice, but a lot of them were already bleaching.

When I was granted a fellowship in Hawai’i to study environmental issues, one of the places I was looking forward to visiting was Hanauma Bay. It was the best place for snorkeling there, blogs said. But when I was finally swimming in the water, I thought, is this it? It didn’t even come close to Pambato.

More than once, when someone learns about how much I have been involved in the environmental justice movement, they would say, taga-Palawan ka kasi. It was borderline offensive for a 17-year-old nascent environmental activist then, because I thought it stripped me off of my volition, like I was just a product of the place I grew up in and nothing more.

One of my favorite photos of my sister Siobe was taken in front of the city capitol when she was three years old. A blur of people in the background, she looks straight into the camera, a sign strung around her neck. The sign reads: Paano naman kami? It was a protest against the permit allowing a mining corporation on the island, Tatay recalled as we flip through the photos.

A decade later, in 2011, No to Mining in Palawan had gone national, and at the forefront were the Palaweño youth, who shared the signature campaign online and passed around physical sign-up sheets among our networks.

If being a Palaweño meant being stubborn enough to fight against a multibillion-peso industry and the corrupt government officials that enabled it, then they were right, taga-Palawan nga ako.

Dividing Palawan

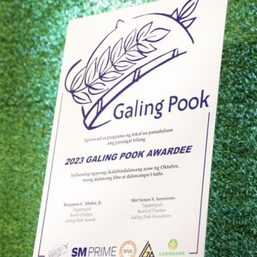

The proposed division of the province has been officially rejected last March 16, according to the results of the recently conducted plebiscite across the island excluding Puerto Princesa City. This is a huge victory not only for the local organizers, religious institutions, and civil society organizations who have made campaigning against this law their full-time jobs these past few months, but more importantly for the Palawan ecological system and the Palaweños benefitting from it.

Had the yes vote won, the division would open Palawan into further ecological exploitation. Existing legislations that protect the island such as the Strategic Environmental Plan (or SEP Law) would have been defunct. For the Tagbanua, Palaw’an, and Batak peoples who have lived and fought for their ancestral lands for decades, this would have meant displacement and uprooting. Taxes would have also increased to pay off overhead expenses required to build new offices and hire new sets of employees. This meant that only corrupt government officials would have benefitted from this division – opening up new positions in the government where they could install their friends and family.

No expansion of political influence can solve corruption and the lack of integrity among our government officials. The division of Palawan would not have solved the problems of the province, and in fact would have further exacerbated it.

Palaweños understood this, and those with significant influence in their communities knew enough to direct their efforts towards increasing voters’ education. The campaign was led by the Save Palawan Movement, a network of civil society organizations, non-government organizations, and people’s organizations advocating for sustainable development and participatory governance in the province. Campaigners and local organizers bore the brunt of political harassment and intimidation these past few months. When the results were officially declared, members sprawled across the island celebrated separately, but had agreed on one thing: David had triumphed over Goliath.

Paano naman kami?

Like most people, the pandemic brought me back home. The organization I was working for that time had instituted a work from home setup, so it didn’t make sense to keep the apartment we were renting in Quezon City. By then it had been eight years since I had stayed in the island for longer than four weeks, only visiting for holidays and summer and semestral breaks when I was in college.

Eight years was long enough to have changed my relationship with the island. At that time my childhood memories of it had already been clouded by the rapid development of the city, which I would see snippets of every time I came back: a new mall here, a subdivision there; by testimonies of people I met who would recall their visit every time they learned I’m a Palaweña; and by curated Instagram feeds of my friends who could afford to stay there and live the quintessential bourgeois island life. At that point, having to go home felt like an obligation, a chore I just had to get over with.

The afternoon after I finished my 2-week quarantine, my ten-year old brother and I walked to the beach for a quick dip before sunset. From the sandbar we noticed some people sprawled across the nearby seaweed bed, their backs bent, their hands tightly gripping their buckets. On our way back to the shore, we chatted a man in his sixties and learned that they were harvesting sikad-sikad, a type of mollusk usually cooked like tinola or with coconut milk. For our dinner, he says grinning.

Over the course of my stay, I have had the pleasure of listening to stories by fishermen, boatmen, our local magtataho, even the manong way past beyond retirement age walking tens of kilometers every day with an ice chest strapped on his arm, selling ice candy. This was the Palawan I grew up in. The Palawan obscured by photogenic beaches, gentrified by private resorts and high-rise hotels. It never becomes easy listening to stories from my people, especially ones mired in intergenerational poverty and individual blame, as though it was not government neglect that had thrust them to the sidelines. I think about the words on my sister’s placard: Paano naman kami?

In December, I got to visit Pambato Reef again. I was confused because the floating hut was visible, signaling that we were within the area, yet the clear waters of my childhood weren’t there, in its place a murky area hiding the corals and fish underneath. We jumped into the water and swam around, and when we got back to the boat, my sisters and I shared the same surprised and saddened expression. What happened? we asked, prodding for answers.

I cannot afford to be despondent for my home. Our land has been plundered by mining companies and pawned off by bureaucrat capitalists for decades, but we have always fought back. Our victory against the division is proof of this resistance. Our continuing fight against mining corporations, palm oil plantations, and many other ecological threats is proof of this resistance. My conversations with people I come across are proof of this resistance. On a tricycle ride on my way home, the driver I was chatting up told me, Tayo-tayo na lang talaga ang magtutulungan no? Iniwan na tayo ng gobyerno.

In its cultural and political diversity, and perhaps in many other ways I couldn’t enumerate, Palawan is a microcosm of the larger Philippine social and political landscape. Our support of politicians has divided us. Our class disparities are staggering. Our social and cultural backgrounds are diverse. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t any underlying issues that should be addressed beneath these differences, because there are. But there is a lesson somewhere in the pockets of this provincial victory that we could all learn from: that setting aside differences increases the power in numbers; and that power in numbers is stronger than anything money or dirty political tactics can buy.

When we left Pambato Reef that Saturday, over 200 boatmen who were members of the Honda Bay cooperative were also packing up before the water got too hot and they couldn’t rid the area of fire corals anymore. Some of them were paid for a day’s work, but some had volunteered. Many of them had pooled in each other’s boats to save gas.

If I were a different kind of person, I would say that this is an allegory of our strength drawn from our sense of community. In our many differences and complex diversities, we all recognize that we are rooted by the same land and the same water that gives us life. Palaweño kasi kami.

Actually, maybe I am that kind of person after all. – Rappler.com

Sasha Dalabajan volunteers for the Save Palawan Movement and works as a media and communications officer for a local nonprofit organization. She was born and raised in Palawan but is currently based in Iligan City.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Edgewise] Preface to ‘A Fortunate Country,’ a social idealist novel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/a-fortunate-country-february-8-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.