SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] When is it okay to commodify culture?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/08/ispeak-commodify-culture-sq.jpg)

When is it warranted to promote and profit from an indigenous culture? Or will it ever be appropriate to earn from someone’s culture?

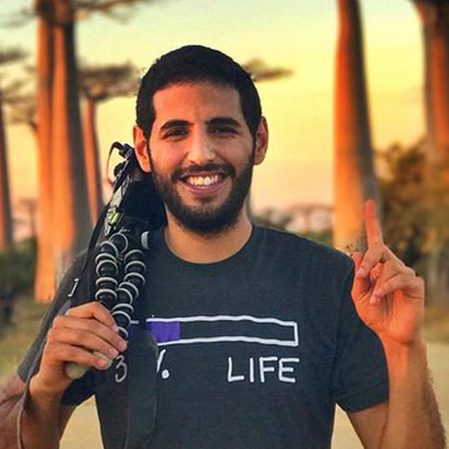

Nas Academy, an educational platform by Nuseir Yassin (also known to many as Nas Daily), came under fire after a relative of Whang-od called its “masterclass” on Whang-od’s tattoo art a scam. According to Gracia Palicas’s Facebook post, Whang-od never signed a contract with Nas Daily, and Whang-od “did not understand what the translators were saying,” perhaps referring to when Nas Daily’s team was in conversation with Whang-od or whoever claimed to speak on behalf of Whang-od.

There is a lot to unpack on the recent hullabaloo involving the Nas Academy. Conversations around the issue mostly centered on the art of “Pinoybaiting” and the commodification of Filipino cultures. While these issues are equally important, I want to focus on the latter as it relates to the primary concern raised by Whang-od’s grandniece.

To be clear, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with cultural commodification. While cultural commodification appears to be a form of “exploitative” profiteering, we must understand that not all forms of commodification are inherently exploitative. To a certain extent, cultural commodification provides livelihood and even a sense of pride for some members of our indigenous communities. In fact, it has long been practiced by some of our indigenous brothers and sisters to promote their welfare and survival in a time when almost everything is commoditized.

Just visit a souvenir shop in a certain province and you will realize that it is commonplace to find commodified forms of local cultures. You may also find the practice in places where some indigenous peoples enthusiastically encourage tourists and outsiders to experience wearing their traditional clothes in exchange for less than a hundred pesos. These examples show that cultural commodification allows indigenous groups to promote their culture and earn money on their terms simultaneously. In other societies, cultural commodification offers the historically marginalized communities avenues to be seen and heard.

What makes cultural commodification unappealing to the eyes of the general population is its supposed consequence on cultures and traditions. The distaste lies in the claim that cultures are “destroyed” whenever they are sold as commodities (hence the popular call to preserve cultures). Yet, the problem with this perspective is that it renders cultures as something frozen in time when individuals, cultures, and societies actually transform over time. As Heraclitus once said, change is the only constant in life. Life is dynamic and so are cultures.

That said, comments that demonize cultural commodification only divert the real issue at hand. Concerning Nas Daily’s Whang-od tattoo online class, the root of the problem is not cultural commodification per se but the alleged exploitation of the Butbut tribe’s culture. There may be significant overlaps in cultural commodification and cultural exploitation, but cultural commodification does not necessarily exploit cultures.

True enough, it is one thing to promote awareness about Philippine cultures to the world positively, but to profit from it is quite another. There is a thin line that distinguishes which forms of commodification are acceptable or unethical. One crosses the line when the appropriation of cultural elements is conducted without the permission from and compensation of the culture bearers. It is abusive, exploitative, and offensive when the endorsement of a culture fulfills the insatiable greed of certain individuals or groups.

Based on what we know so far, following the post of Whang-od’s grandniece, it appears that Nas Daily “spoke to someone and gave some money and will share profits” to a certain individual who appears to be connected to Whang-od. If this is true, then why should we perceive the online course as ill-intentioned?

Featuring Kalinga’s traditional tattooing is not necessarily exploitative so long as Nas Daily is committed to sharing profit with Whang-od and other culture bearers. If the program intended to benefit both parties, and if it intended to provide a platform for Whang-od to promote Butbut culture, then there is nothing essentially wrong with the profiteering it will involve.

Then again, it is always best that we hear the other side of the story before arriving at any conclusions. – Rappler.com

Fernan Talamayan is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Social Research and Cultural Studies, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan. He holds a master’s degree in History from the University of the Philippines Diliman and a second master’s degree in Sociology and Social Anthropology from the Central European University, Hungary.

Voices features opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Ilonggo Notes] The foremost Filipino engraver, sadly unremembered, needs to be given his due](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Figueroa-.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=265px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.