SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I wrote the piece below a decade ago in February 2006, the 20th anniversary of people power on the main highway in Manila, EDSA.

At #EDSA30, not much has changed.

The fact that so few Filipino millennials care about #EDSA30 is a collective failure of our society. Succeeding administrations did little to change the fundamental structure of governance and bring a better life to its people.

Over the years, too many interest groups used people power as a political tool, breeding cynicism and distrust, robbing it of its spirit and meaning.

What I wrote a decade ago is even more relevant today.

THE PARODY OF PEOPLE POWER (February 2006)

Last year, I decided to end nearly two decades working for CNN in Southeast Asia to come home to the Philippines. As it turned out, I was bucking the tide because respected polling survey Pulse Asia said that a third of Filipinos want to leave the country for good, part of an ongoing exodus of overseas workers who insulate the economy. Nearly 8 million people, or about one-tenth of the population of about 80 million, send home an estimated $10 billion a year, or one-tenth of the gross domestic product. They are the country’s largest dollar earners.

It certainly didn’t seem like a good time to turn my dollars into the local currency, the peso. The Philippines again had become the sick man of Asia. Political infighting had become so rampant little was moving in government. Although the currency and stock market have recorded gains in recent months, true economic reforms have yet to be accomplished while the gap between the rich and the poor continues to grow. The government says it will close the budget gap, but any economic gains are swamped by a population growth rate of 2.3% a year – one of the highest outside Africa – with a much lower food production rate of 1.9%.

Despite the statistics, I made the decision to come home – the second time I did so in the past 20 years. Although I was born in the Philippines, my family left for the United States after Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972. In 1986, I came home in search of roots.

Press freedom and the people’s network

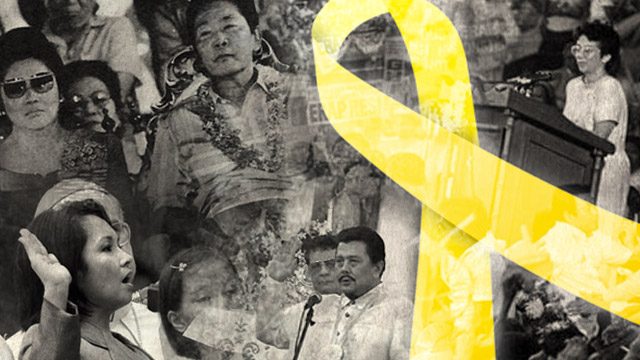

As a fresh college graduate, I walked into the government television station thrilled with the possibility of helping turn this former propaganda machine into a true People’s Television network (reflecting the new name it adopted – People’s Television 4). From an instrument of repression, it became the voice of freedom. It was an exhilarating time full of endless possibilities, giving life to the literal meaning of people power. Excitement gripped our motley crew: potential anchors auditioning live, to be chosen by the people – who themselves were flush from an unimaginable victory ending the 21-year rule of Ferdinand Marcos. That was the birth of “people power,” when hundreds of thousands of people gathered to protect a military in revolt and faced down a dictator with nothing more than prayers and songs. The iconic images of nuns stopping tanks and children putting flowers in the barrels of guns powered democratic dreams globally – in South Korea, Pakistan, China, Burma, East Germany, Bangladesh, Nepal and Indonesia.

People power meant freedom of the press, something nearly forgotten for this generation of journalists, most of whom first labored under the outright censorship of martial law followed by something more insidious and damaging: self-censorship. In the government station, I struggled with the habits left behind – scripts so safe the words were devoid of meaning, but each word I rewrote was a death knell for the past. (That was part of the reason I cringed when the head of the national police recently repeatedly called for “self-censorship.”)

Without the media, people power wouldn’t have happened. After all, the call to help, to assemble in the streets were broadcast on radio and later, messages of freedom came from the former government station. Euphoria infused the entire society: it was a moment of redemption. Spontaneously discovered, people power was created by a failed military coup, the calls of the Catholic Church (in Asia’s largest Roman Catholic nation) to help the soldiers, the journalists who risked their lives to get the message out, alternative political figures, and the hundreds of thousands of people from all classes of this economically stratified society who rushed into the streets. In those moments of uncertainty, Filipinos took a stand and risked all they had. Victory created unrealistically high expectations and 3 primary national goals: reconciliation; rebuilding democratic institutions; and economic recovery and reform.

Failed expectations

Twenty years and 4 presidents later, those goals remain unfulfilled. It is painful to look back on those days and see so many ideals corrupted and dreams betrayed.

Instead of creating a meritocracy – leveling the playing field so leaders are the best and the brightest – politicians returned to the familiar: elite politics, giving economic and political power back to about 8 oligarchic families pushed aside by Marcos. That aggravated the gap between the rich and the poor and pushed more Filipinos overseas to look for greener pastures – draining the country of the vital middle class needed for regeneration.

Instead of an enlightened and professional mainstream media acting as the fourth estate, we have journalists corrupted by vested interests, some for sale to the highest bidder – with not enough attention focused on skills and ethics. Instead of professionalizing the military, soldiers empowered with a political agenda never really went back to the barracks – plotting at least 10 more coup attempts in succeeding years. Instead of rebuilding institutions, corruption and patronage undermined democratic processes – leaving Filipinos powerless to effect real change.

Through all sectors of Philippine society, the lack of transparency and accountability allowed backroom deals that hampered true development at every front.

What’s clear is that American-style democracy in the Philippines has largely failed. More form than substance, it has given back little to the people who flocked to the streets in 1986. Another survey done by Pulse Asia last January showed that only 36% of Filipinos now believe Marcos should have been removed by people power.

Back to where we began

Twenty years later, this nation is right back where it started: questioning the mandate of its president – like in 1986. For President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the distribution last year of wiretapped telephone conversations, allegedly between her and an election official, triggered her latest and most serious political crisis. Allegations of vote-buying marred her victory and led to failed impeachment processes and an alleged coup attempt on the eve of the 20th anniversary of people power. This is where freedom without accountability, without responsibility leads – for the people, the politicians, the military and the press.

For the people, the mood has never been worse, not even under Marcos. According to Pulse Asia, Filipinos have hit their lowest point emotionally – at the end of last year, 77% of Filipinos surveyed said the quality of their lives had deteriorated – and that they expected it to get worse this year. According to Pulse Asia, Filipinos are at their most pessimistic point historically – even worse than 1983, a trigger year against Marcos, the year his political nemesis, Benigno Aquino Jr, was assassinated. That was the spark which galvanized the anger and pushed Aquino’s wife, Cory, to power.

Cory’s mistake

In 1986, the situation was black and white: Cory Aquino was good, Ferdinand Marcos was evil. Those days are over, partly because Mrs Aquino’s attempts to rekindle people power and repeat her extra-constitutional triumph challenged her primary legacy – democracy – and further weakened the fledgling institutions she left behind. The lines have blurred and grays now dominate the political landscape, starting with Mrs Aquino herself who led mass protests against her three successors. She called people out on the streets against the first, former general Fidel V. Ramos, to stop him from changing the Constitution in 1998 to keep himself in power. She helped push the second, popular movie actor Joseph Estrada, out of power in a repeat of her 1986 triumph, a bastardized version dubbed People Power 2, which brought Gloria Macapagal Arroyo to power. Now, Mrs Aquino is demanding President Arroyo’s resignation.

She is not alone. According to another Pulse Asia survey, 65% of Filipinos say they want President Arroyo out. Most Filipinos say they have lost hope in the political system and in politicians. In fact, according to qualitative surveys, the rich and the poor have never been so separate and so distinct, with the rich insulated from the economic effects of an inefficient system and the poor reaching new levels of desperation. How did we get to this point?

Revisiting the past

In 1986, all the elements came together – giving Mrs Aquino the opportunity to redefine this nation’s feudal and oligarchic past, but in the end, she failed to rise above her class. Although she freed the economy from many government-imposed restrictions, her policies reinforced existing inequalities, and economic and political power merely changed hands from one faction of the ruling elite to another. It gave new life to oligarchic politics – in pre-Marcos days, about 8 families controlled most of this country’s wealth. That reinvigorated a feudal political system, which takes advantage of social inequality to keep intact a mass base for patronage.

The return to elite politics not only constrained economic growth, it also aggravated mass poverty, setting the stage for the rise of Joseph Estrada, popularly known as Erap, a movie actor who played countless Robin Hood characters. He won the 1998 elections on the slogan of “Erap para sa mahirap (Erap for the poor)” and became a rallying symbol for the poor. But corruption became so flagrant under him that the middle class rebelled. He became the first Philippine president to face impeachment charges for corruption, and the trial – held by the Senate – was so flawed that, during the televised proceedings, when a decision was made not to accept key evidence against the president, some senators walked out and the people took to the streets.

It was history strangely revisited: the middle class and elite protested against Estrada while his poorer supporters held their own demonstrations in another part of the city. The military became the deciding factor, again reinforcing its kingmaker role and continuing its forays into politics. Less than a week into the protests, the military abandoned Estrada and threw its lot behind his vice president, Gloria Arroyo, who became a symbol of middle class aspirations for smart and good governance. She became the nation’s fourteenth president on Jan. 20, 2001, at the same spot where people power succeeded in 1986.

People power vs mob rule

People Power 2 was tainted by a key difference from the first: the protests that brought Mrs. Arroyo to power deposed a duly elected president, not a dictator. That would haunt the first few months of her presidency as Estrada’s supporters tried to launch people power 3 against her on May 1, 2001, blurring the lines further between people power and mob rule. Filipino society split on economic lines: Estrada’s supporters came from the bottom rung, while Mrs Arroyo was backed by the middle and elite classes. She survived the split, but the damage was done, and she said she was forced to compromise in order to hold her unwieldy coalition together.

Although she won her own mandate in the May 2004 elections, even that was questioned after wiretapped telephone conversations were released to the media, raising charges of election cheating, charges Mrs Arroyo denies. But those tapes triggered impeachment processes which have kept her constantly battling. This is a presidency under relentless siege.

The excesses and failures of power

On the eve of the 20th anniversary of People Power, Mrs Arroyo prevented a People Power 4 by declaring a state of emergency: she claimed that the political opposition, elements of the extreme right and the extreme left, and “reckless elements of the national media” were working together to mount a coup against her government. Police immediately banned political rallies scheduled for the anniversary, but not everyone followed. Some respected leaders continued their plans and protested the declaration. It turned into a parody of people power when police dispersed them with water cannons and carried out warrantless arrests on nationwide television at the site where people power had already overthrown two presidents. Then came the moves against media, starting with threats and the raid on the newspaper, the Daily Tribune.

I cringed when I heard government officials threaten to close print and broadcast media institutions, when I saw their efforts to divide and to intimidate journalists – all in the cause of calling for “responsible journalism.” That is the reason I joined a group of senior journalists and media institutions to file a case against government officials to prevent them from intimidating and threatening the media. This is the first time journalists have come together on this scale since martial law. Looking back to 1986, there is obviously fear on the government’s side – that people power could now be turned against the same politicians who took advantage of it to gain power. Regardless of motivation, freedom of the press is enshrined in the Bill of Rights, in the Philippine Constitution; it is not preconditioned on “responsible journalism.”

To be sure, Filipino journalists have failed to live up to our dreams in 1986. A few short years later, journalists with vision, who didn’t want to compromise on standards and ethics were forced to leave mainstream media and form their own small hand-to-mouth outfits: for print, there was Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, Newsbreak, and for television, Probe Productions, Incorporated. Mainstream media fought its own demons of commercialism and vested interests, a battle that continues today. That is part of the reason I left CNN and returned to the Philippines: we are working on upgrading our skills, building in more context, adding analysis and a true understanding and appreciation of ethics. We are aware of the gap between local and international standards. It is certainly not up to the government to mandate bridging that gap under its specified “standards.” With its vested interests, that would be called propaganda.

My life is full of irony nowadays: I work in the same buildings I entered in 1986 with so much hope. Once the government station under Marcos, it transformed overnight into People’s Television 4. A year later, the buildings were returned to the Lopez family, the original owners, one of whom was jailed when the buildings were taken over by the government under martial law. Working here reminds me of the cycles of history, the excesses and failures of power, and the role media plays. As head of news for ABS-CBN, the largest Filipino television network, I see the daily search for meaning and hope. When politicians change alliances so often, you lose track of what they stand for. When symbols lose their meanings and when government after government fails to deliver, we have a nation in deep crisis.

Our life today

The daily and exhausting drama of real-life political theater and the repeated attempts by the military and politicians to replay the now tired script of people power – all this have only succeeded in trivializing its meaning. In the end, people power became a parody of itself. It prevented the painful but necessary growth of all sectors of a society that needed to learn accountability for its choices during elections and a government bureaucracy that needed to institute systems of transparency so it could be held accountable. In many ways, the politicians, the military, the Church, the press and the people needed to mature in perspective and tactics, to accept that democracy is about more than just elections.

People power should have never become a political tool; it was a once-in-a-lifetime act that should have been followed by the hard work of building democratic institutions. That never happened. That is the work that, 20 years later, desperately needs to be done. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Ilonggo Notes] The foremost Filipino engraver, sadly unremembered, needs to be given his due](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Figueroa-.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=265px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.