SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

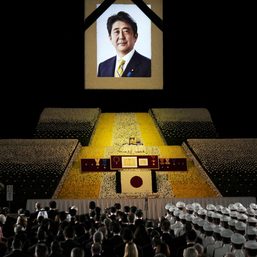

November 14, 2017, last night of the ASEAN Summit in Manila: Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe entered the Diamond Hotel, and I aimed my camera at him. He looked to my direction, nodded, and smiled.

Don’t get excited. He didn’t know me from Izanagi, but was acknowledging the two persons beside me who were traveling with him. He walked briskly, and I was left with a blurred photo of him just a few meters away from me.

“You’ll have plenty of opportunity to meet him,” I was told. “He’ll still be prime minister for some time.”

December 12, 2018, nearly 3 months after Abe was given a fresh mandate as head of government: I had been invited to tag along for the taping of an interview, for a New Year’s Day broadcast, on an issue that Abe had always prioritized: the return of Japanese citizens abducted by North Korean agents decades before. (You can read the English translation of the interview here, here, and here.)

So there was the crew of Genron TV, Sankei Shimbun, JAPAN Forward, and Seiron magazine – and the “journalist from Manila.” At the end of the recording, the plan was to let me stand beside him in the group photo. But my soul sister (a political journalist who had covered him) nudged me towards the Prime Minister: “Go, talk to him.” In a flurry of casual talk in Nihongo translated for me in real time, they told him who I was and what I did.

I told him about our first “encounter” at the summit in Manila, and he recalled that he spoke to Donald Trump about how important it would be for the US president to be there. (Context: the leader of the free world, barely a year in office then, had initially considered skipping the summit.)

I believe I was able to tell the Prime Minister that Filipinos appreciated Japan for being our top source of overseas development assistance (ODA). I remember him say Japan would not have done anything less because it had always considered the Philippines a good friend. But, hontoni, for the most part I just got tongue-tied. It wasn’t because I didn’t know what to tell him, but because I wanted to tell him a lot, and I couldn’t pack them into a few minutes of chance encounter.

August 28, 2020: A few days after he made history as the longest-serving prime minister of Japan, and with a year left to his term, Abe resigned due to health reasons.

World leaders have since sent him messages of appreciation and best wishes. The international press is divided between those giving a fair assessment of his 12 years in office and those just hastily calling his administration a failure. (I recommend you read “The Abe Legacy: How Japan Got its Mojo Back,”“A reformer bids farewell,” and “Abe Shinzo has left an impressive legacy.”)

And here I am – that “journalist from Manila” – finally sharing with you what I would’ve told Prime Minister Abe if I could only hold him up longer at that December 2018 meeting in Chiyoda-ku.

***

“Japan is among the countries that Filipinos deeply trust, a close second to the United States.”

In contrast, at the bottom of the list of countries included in Pulse Asia’s surveys is China, with whom both our countries have maritime disputes. Also deeply distrusted by Filipinos is Russia, with whom Japan has territorial disputes as well.

Early into the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, whose coziness with China bordered on treason, overall trust in China was at 38% (December 2016), then 37% (March 2017). Meanwhile, the overall trust in Japan was at 70% and 75% in those periods.

(After our meeting, Pulse surveys showed trust in Japan rose further from 75% in December 2018 to 79% in June 2019, against China’s, falling from 39% to 26%. In December 2018, Social Weather Stations confirmed what its polls since 2016 had been showing: that most Filipinos didn’t share Duterte’s trust in China. In fact, in every 10 Filipinos, only two believed Beijing had good intentions for Manila.)

“Filipinos know Japan has helped us beyond providing the biggest chunk of development assistance.”

If a big majority of Filipinos trust Japan, it may be because, when it says the Philippines is a valuable ally, it matches its declaration with action.

As of June 2018, a little over 40% of the ODA received by the Philippines were from Japan. That was equivalent to $6.1 billion. In the many years that Japan had been the Philippines’ top source of ODA, the 3rd would always be the Asian Development Bank, which, far from coincidence, is a regional bank first conceptualized by the Japanese and where Japan has always been one of the largest shareholders.

It’s common knowledge in the Philippines that Japan helps with improving our transportation system and our capability to adapt to climate change (you only need to see the map of Japan International Cooperation Agency’s major projects).

Little known is the huge role it quietly played in the success of the peace talks between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. I should know – I was in touch with people at the Japanese embassy while they refused to publicize their efforts. President Noynoy Aquino later revealed that Japan “provided an environment where both sides could see the sincerity of their dialogue partners.”

Aquino referred to Japan as a “gracious and faithful ally,” and I would agree. It has been doing its part in building a friendship with the Philippines after both countries “[overcame] the scars of the past,” the enmity during World World II.

(By March 2019, the latest data available, grants and loans from Tokyo would comprise nearly half of the ODA, at $8.3 billion. Foreign Secretary Teddyboy Locsin would tell the Asia Society in New York in September 2019: “[Agreements with China] hardly materialize, and if you would compare to Japanese investments and official assistance, [they’re] nothing….. There’s apparently a phenomenon…of a rising Japan and we’re feeling that.”)

“Thank you for relaxing rules to allow more Filipinos to visit or work in Japan.”

Although a big majority of the Japanese prefer that their country no longer increase, and if possible decrease further, the number of migrant workers it allows, Abe risked pushing a policy that would bring in those foreigners. In his long-term view of addressing the economic impact of Japan’s anticipated demographic contraction, workers from other Asian countries will benefit as well.

From the Philippines alone, more than 50,000 skilled workers will be potentially hired until 2025 under the new immigration rules for foreign workers. That will be a big leap from only 2,200 that Japan was able to hire in special arrangements under the Japan-Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement of about a decade ago.

Not just workers but tourists from the Philippines are enjoying the relaxed entry rules. Japan started easing visa requirements in July 2013, half a year after Abe-san assumed the premiership a second time. These were further eased about a year later, until in August 2018 Japan started making it easier for Filipinos to get multiple-entry visas. A tourist can normally stay for a month. (To the young ones who don’t realize what a big improvement this is: When I first got my single-entry tourist visa nearly two decades ago, Filipino workers in Japan were surprised that it would’ve allowed me to stay for 15 days because visas then were normally for only 5-7 days.)

“The Philippines appreciates Japan’s security assistance, which you’ve maximized despite legal limitations.”

In January 2018, the Philippine military deployed a patrol plane to Panatag Shoal (also called Scarborough Shoal) in the West Philippine Sea, flying as low as 800 feet around the rock formations that had been controlled by China after a standoff with Philippine vessels 6 years earlier. It was one of the few times, if not the first time, that the Chinese coast guard didn’t air any warning.

That plane was a donation from Japan. It was one of the 5 aircraft covered by the first agreement that Tokyo crafted after its parliament changed a law to allow the donation of secondhand defense equipment to less-developed countries.

When our two countries signed in March 2016 a defense equipment and technology transfer agreement, it was among the first of such nature that Japan had signed with other countries. It has since given the Philippine coast guard, navy, and air force patrol boats, rescue and patrol ships, reconnaissance aircraft, thousands of helicopter spare parts, and more – turning Japan into what a Manila-based think tank called “the Philippines’ most reliable and important security partner.”

Its security assistance was not limited to the military. Japan donated 100 patrol vehicles to the Philippine National Police for the latter’s counter-terrorism operations. P225.6 million ($4.65 million) worth of vehicles weren’t something to sniff at.

Before all these, Japan could only extend training and capability-building assistance to the Philippines’ security sector.

Maybe only a few of Filipinos realize that, while Japan strengthened its security ties with us and other Asian nations, it’s been facing a difficult battle at home to completely empower its military.

Abe’s push for the revision of Japan’s constitution has been demonized by western powers and the domestic opposition as if pacifism and equipping a country’s defense force to be able to actually protect its people from aggression are mutually exclusive.

Japan’s constitution – currently more than 70 years old – was drafted by the Americans after WWII. The purpose was for “Japan to be permanently disarmed…even if detrimental to its own self-preservation,” veteran journalist Yoshihisa Komori would later write.

“Article 9 bans Japan’s possession of any offensive weapons and prevents the country from exercising the right of collective self-defense, even though collective self-defense has been recognized as an inherent right of sovereign states…. Japan’s constitution bans it from carrying out this inherent and universal right,” he continued.

I can imagine how frustrating this is. Covering efforts at constitutional revision in the Philippines for decades, I’ve seen how any and every attempt is reflexively considered as bad or wrong.

(When Abe stepped down, their constitution remained untouched.)

***

You ask, will I tell him these things should I get the chance to meet him again?

Yes, but I will also thank him that, during the coronavirus pandemic, when his administration gave each resident in Japan a ¥100,000 subsidy, they included Filipino citizens who had been there for at least 3 months. I’ll acknowledge the generous terms that Japan has given my country for the P23.5-billion ($485.23-million) loan for our pandemic response. And I’ll express my appreciation that, while all nations had their own challenges to deal with in this global health emergency, he committed Japan to sharing the vaccine with developing countries, and urged the 6 other most advanced economies in the world to do the same.

But first I’ll ask him about movies. I heard that he had wanted to make them before he was thrust into carrying on the political legacy of the family. I’ll start with The Eternal Zero (Eien no Zero), the 2013 film about World War II that reportedly “deeply moved” him. Critics quickly interpreted his reaction as militarism and the glorification of suicide pilots. I just remember myself bawling at the close of Takashi Yamazaki’s masterpiece.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] The sharp power challenge: Defending PH from within](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/sharp-power-challenge-march-5-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Rappler Investigates] The guns of Apollo Quiboloy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/quibs-guns-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=412px%2C0px%2C1280px%2C1280px)

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Why is Japan Home Centre accepting sibuyas as payment?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/japan-home-center-february-3-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=188px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.