SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Public furor over the pork barrel scam combined with a more aggressive tax collection campaign by the BIR in recent months has yielded some fairly strong sentiments about the state of taxation in the country. At one point, social media flooded with ideas of staging a tax boycott, or calls for voting rights to be given only to taxpayers. (As if the poor don’t pay taxes at all – but that should be the subject of another op-ed). If the middle class feels the heavy weight of taxation, does the evidence bear this out?

Public furor over the pork barrel scam combined with a more aggressive tax collection campaign by the BIR in recent months has yielded some fairly strong sentiments about the state of taxation in the country. At one point, social media flooded with ideas of staging a tax boycott, or calls for voting rights to be given only to taxpayers. (As if the poor don’t pay taxes at all – but that should be the subject of another op-ed). If the middle class feels the heavy weight of taxation, does the evidence bear this out?

A casual analysis of tax policies in the ASEAN suggests that the Philippines has the second highest average tax rate (after Vietnam and Thailand). On the other hand, Singapore has the lowest marginal tax rate at both ends of its tax bracket spectrum, at 20% for the wealthiest and 2% for the lowest qualifying income tax payers. (Compare this with 32% and 5% for the Philippines.) If we also consider the value-added taxes in ASEAN, the Philippines comes on top (or near the top) of the most taxed in the region.

| Table 1: Marginal Tax Rates for ASEAN Countries | |||

| Country | Tax Rate for Highest Income Bracket |

Tax Rate for Lowest Income Bracket |

VAT Rates |

| Vietnam | 35% | 5% | 10% |

| Thailand | 35% | 5% | 7% |

| Philippines | 32% | 5% | 12% |

| Indonesia | 30% | 5% | 10% |

| Malaysia | 26% | 2% | 6% |

| Myanmar | 25% | 5% | 5% |

| Laos | 24% | 5% | 10% |

| Cambodia | 20% | 5% | 10% |

| Singapore | 20% | 2% | 7% |

Source: AIM Policy Center compilation of tax structures for ASEAN

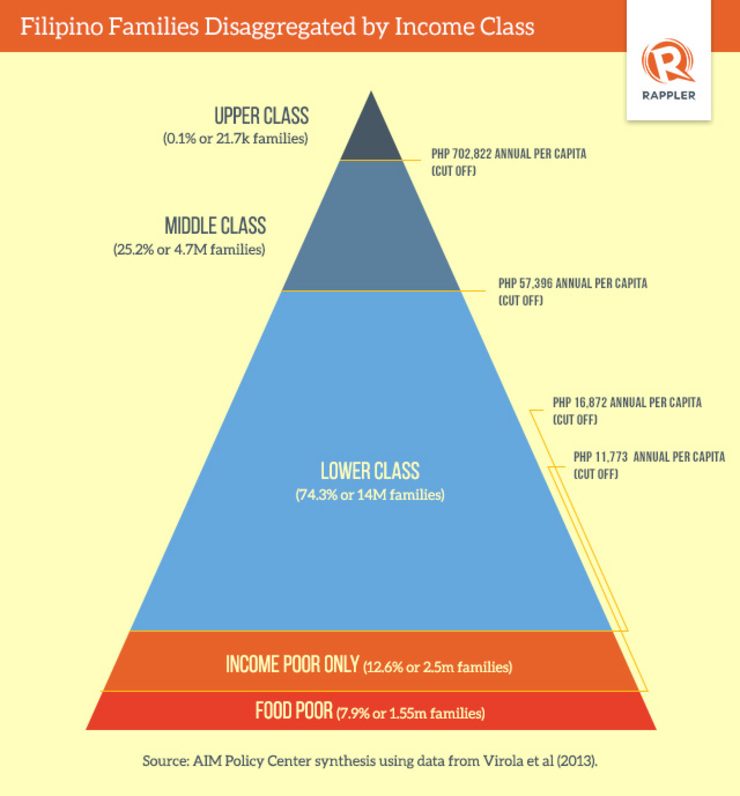

If we focus on the Philippine middle class, Virola et al (2013) provide a handy description based on their statistical analysis of the distribution of incomes in the country. In order to be considered part of this group, one’s annual gross income should range from about P64,317.00 to P787,572.00. That’s roughly P5,359.75 to P65,631.00 in income a month. We acknowledge that many of you will find this range too large. But if we take this to be a useful illustrative guesstimate for now, then that study indicates that there are 4.66 million families (roughly 25% of the total population) in the middle class. (Compare this with roughly 14 million families (or 75% of the population) belonging to the lower class, of which over 4 million families fall below the poverty line.)

Bracket creep

It seems one primary concern for many in the middle class is the growing sense of over-taxation. One way this can happen is if the tax brackets are not adjusted for inflation – over time, this will likely result in rising nominal incomes pushing a growing number of income taxpayers into much higher tax brackets, even as their real (or inflation-corrected) incomes have not increased (or not by as much).

“Bracket creep” could contribute to what economists call “fiscal drag”—a weakening of aggregate demand due to excess taxation of a growing number of taxpayers. And as more taxpayers are pushed to the same tax bracket (wherein incomes still have a high disparity even within that bracket), then the progressiveness of the tax system may decline over time. (Note that progressivity is better achieved by imposing higher tax rates on those with greater capability to pay, i.e. the wealthy. This becomes less likely when more and more people fall into the same tax bracket and face the same tax rate.)

In our recent study at the AIM Policy Center, we turned to data from the Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics (BLES) in order to analyze 362 occupations spanning 41 industries, comparing their average gross annual wages for 2008 and 2012. The comparison also took note of the change in the applicable marginal tax rate for each occupation. Of the 362 occupations,101 occupations (28%) indicated higher applicable marginal tax rates in 2012, implying that more taxpayers probably shifted to higher income tax brackets since 2008.[1] Examples of middle class occupations whose marginal tax rates have increased to 32 percent are featured in Table 1.

If any of our readers encumber these jobs, then, congratulations! You now face the same tax rate as the wealthiest people in the country! (And that includes movie and television actors who make up to P12 million per month in income.)

| Table 1. Occupations Whose Marginal Tax Rates Have Increased to the Highest Rate | |||||

| Occupation | Industry Group | 2008 Gross Annual Income (Philippine peso) | 2012 Gross Annual Income (Philippine peso) | 2008 Marginal Tax Rate (%) | 2012 Marginal Tax Rate (%) |

| Art Directors | Animated Films and Cartoons Production | 410,532.00 | 557,502.60 | 30 |

32 |

| Electronics and Telecommunications Engineers | Computer and Related Activities | 321,456.00 |

663,172.87 |

30 | 32 |

| Systems Analysts and Designers | Computer and Related Activities | 272,004.00 |

600,324.52 |

30 | 32 |

|

|

Insurance and Pension Funding Except Compulsory Social Security | 427,500.00 | 574,515.11 | 30 | 32 |

| Mechanical Engineers | Manufacture of Plastic Products | 158,520.00 | 521,757.48 | 25 | 32 |

| Mining Engineers and Metallurgists | Metallic Ore Mining | 287,580.00 | 540,060.88 | 30 | 32 |

| Geologists | Non-Metallic Mining and Quarrying | 240,000.00 | 570,936.55 |

25 |

32 |

Source: AIM Policy Center calculations using data from the BLES

[1] The interested reader may wish to read the annex providing details of these 101 occupations whose incomes and marginal tax rates have increased from 2008 to 2012.

Reform proposals

Our tongue-in-cheek comment aside, clearly, there is scope for considering income tax reforms when too many people with such disparate incomes end up with the same (in this case the highest) tax bracket. This goes against the principle of progressivity, and it most likely exacerbates inequality.

In response to these issues, and motivated by the desire to give the middle class some tax relief, tax reform proposals have been put forward by Senator Juan Edgardo M. Angara (Senate Bill 2149), Senator Paolo Benigno A. Aquino IV (Senate Bill 1942), and Senator Ralph G. Recto (Senate Bill 716). Table 2 summarizes the tax revenues under the existing tax regime (i.e., the baseline) and the estimated tax revenues based on the senators’ proposals. For purposes of comparison, the relative change from the baseline revenue is also reported for each of the proposals.

| Table 2. Estimated Tax Revenues from Existing Tax Regime and Tax Proposals | ||

| Tax Regime | Estimated Total Revenue (PhP) | Estimated Revenue Loss (Compared to the Baseline Revenue) (PhP) |

| Existing Tax Regime (Baseline 2012) | 35,446,924,895.91 | NA |

| Sen. Angara’s Proposal (2015) | 34,539,425,850.18 | 907,499,045.73 |

| Sen. Angara’s Proposal (2016) | 30,039,217,117.84 | 5,407,707,778.07 |

| Sen. Angara’s Proposal (2017) | 26,432,913,989.35 | 9,014,010.906.56 |

| Sen. Aquino’s Proposal | 35,065,249,890.99 | 381,675,004.92 |

| Sen. Recto’s Proposal | 33,595,897,578.69 | 1,851,027,317.22 |

Source: AIM Policy Center calculations using data from the BIR.

Please refer to Mendoza et al (2014) for the full elaboration

What happens to revenues and progressivity?

Predictably, providing relief implies a possible reduction in tax revenues (at least in the short term). Senator Aquino’s proposal could have the lowest revenue loss at 1 percent of the estimated total revenue under the existing tax regime. (The main reason is that they also propose to increase the tax rate of the wealthiest.) This is followed by Senator Recto’s proposal (at 5 percent of the total revenue under the existing tax regime).

Initially, Senator Angara’s proposal could decrease total revenue by only 3 percent. In 2016, the decrease could rise to about 15 percent. In 2017 (and onwards, once the new regime is made permanent), the decrease in revenues compared to the baseline (2012) revenues, could increase to 25 percent for the Angara proposal. This is largely because his proposed tax cuts are the deepest, and they also apply (at least in part) to some of the wealthiest in the country.

It should be noted that all these figures are based on comparative static calculations that do not accommodate behavioral responses or adjustments by taxpayers. They are merely illustrative, given the information on income taxpayers that are currently publicly accessible. In other countries where tax cut discussions are much more advanced, there are arguments suggesting that tax cuts for the wealthy could translate to more spending, investments and job creation.

For now, it suffices to say that the 3 income tax reform proposals could have different consequences on inequality across income tax payers and on total revenues in the short and medium terms. Nevertheless, based on our estimates, the expected impact on inequality among income tax payers all appear quite marginal.

The preceding analysis is illustrative and should not be considered as a final assessment of the 3 different income tax proposals being deliberated in the Philippine Senate. The three Senators should be credited for pursuing these reforms, which (hopefully) will also help elevate the awareness of the public to revisit issues such as tax progressivity and equity for the country’s income tax regime.

Reforms in public finance cannot just focus on the spending side (e.g. shutting down PDAF, promoting bottom up budgeting, and improving transparency and participatory governance reforms in budgeting). Addressing revenue-side issues will go a long way in winning back the hearts and minds of taxpayers. (And yes, that also includes the poor.) – Rappler.com

Ronald U. Mendoza is Associate Professor of Economics and Executive Director of the AIM Policy Center, while Enrico Gloria is an Economic Research Associate handling public finance research. The views expressed herein are theirs and are not necessarily those of the Asian Institute of Management.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.