SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This September, leaders from across the world will gather at the United Nations (UN) to put forward a new development agenda called the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the successor to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The SDGs put forward a shared vision of where we want to see the world to be in 2030, in terms of economic, social, environmental, and governance conditions, with statistics to be produced by member states in 2015 to serve as baselines for monitoring progress.

At the close of the millennium 15 years ago, 189 UN members adopted the Millennium Declaration which committed humanity to poverty reduction and related goals. The following year, the UN Secretary General’s Road Map for implementing the Millennium Declaration formally defined eight goals, supported by 18 quantified and time-bound targets by 2015, and 48 statistical indicators, which subsequently became known as the MDGs.

For instance, for poverty reduction, the goal was to reduce by half the proportion of people in extreme poverty from 1990 to 2015, with one of the indicators for measuring this poverty reduction goal and this specific target as the percentage of the population with incomes less than $1 a day (in 1990 prices, or $1.25 in 2005 prices).

The number of targets and indicators for monitoring the MDGS were subsequently further expanded to 21 targets and 60 indicators (see Table 1).

Table 1. Number of MDG Targets and Indicators per Goal

|

MDGs |

Number of Targets |

Number of Indicators |

MDGs |

Number of Targets |

Number of Indicators |

|

3 | 9 |  |

2 | 6 |

|

1 | 3 |  |

3 | 10 |

|

1 | 3 |  |

4 | 10 |

|

1 | 3 |  |

6 | 16 |

Source: UN

The MDGs set forth a framework for global aid discussions, and provided an agenda not only for the world and its member states, but also within countries. Across the world, progress has been observed in many of the MDGs, especially in reducing extreme poverty, and in improving access to education and health services.

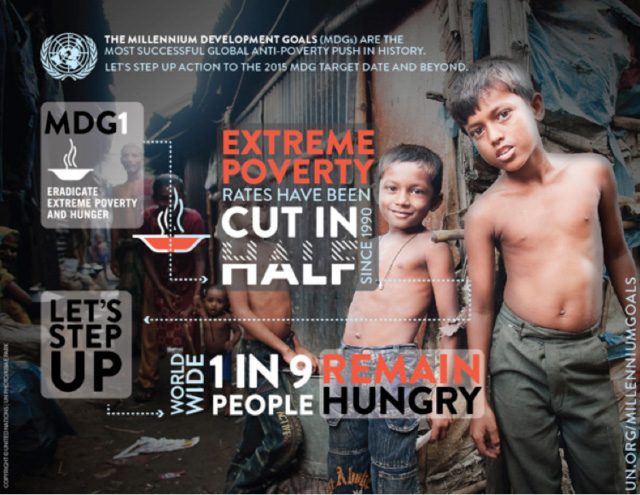

The first of the MDGs on poverty reduction has been achieved ahead of the 2015 deadline: the proportion of people with incomes less than $1.25 a day (in 2005 prices) in 2010 (18 percent) was already half the 1990 proportion (36 percent). Despite population growth, 700 million fewer people lived in conditions of extreme poverty in 2010 than in 1990. Still, over a billion (1.2 billion) people are living in extreme poverty.

The UN, in its MDG Report 2014, noted that aside from achieving the extreme poverty reduction target ahead of the 2015 deadline, the world has also already met its targets on access to safe drinking water and improving the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers. In addition, the targets on gender equality in primary and secondary education and the incidence of malaria are projected to be met by 2015, although gender disparity was noted to be still prevalent in higher levels of education. In addition, results have been observed in the fight against malaria and tuberculosis globally.

Hunger, child undernutrition, and child mortality also have continued to decline. Across the world, the political participation of women has continued to rise. Primary school participation and access to improved sanitation has also risen.

Uneven progress

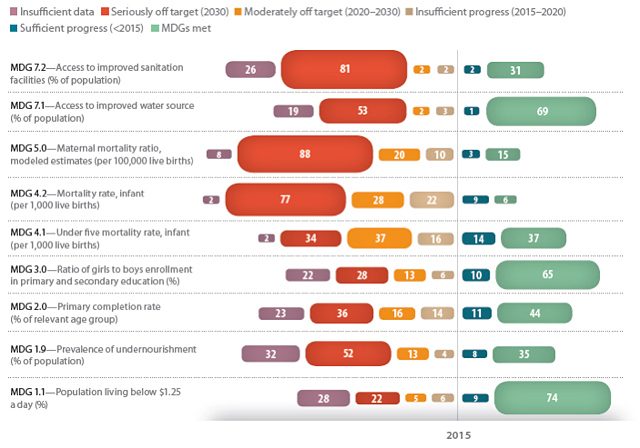

But while much progress on the MDGs has been achieved, the rate of progress has been very uneven across regions, across countries, and across the Goals.

Sub-Saharan Africa bears the brunt of development challenges with continuing food insecurity, very high child and maternal mortality, a large number of people living in informal settlements, an increase in extreme poverty, and an overall shortfall in attaining a majority of the MDGs.

Latin America, the transition economies, as well as the Middle East and North Africa, have shown slow or no progress on some of the MDGs,with persistent (and even rising) inequalities preventing progress on attaining other MDGs. Asia has yielded the fastest progress in reducing poverty and improving access to social services, and yet, even in Asia, the number of people living in extreme poverty are in the hundreds of millions of people.

Figure 1. Extent of progress toward achieving the MDGs, by number of countries.

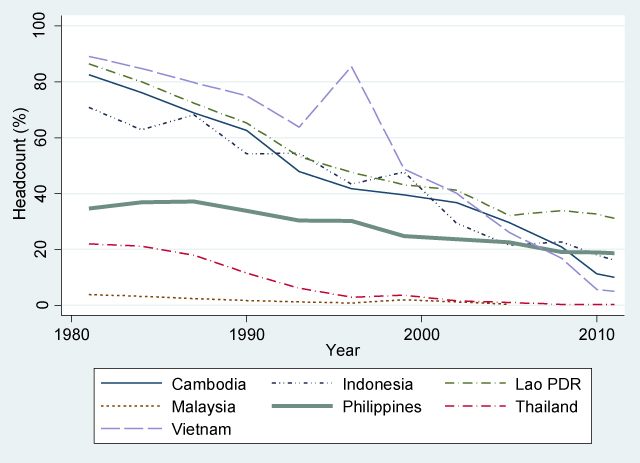

In the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), many member states have either had low poverty headcount rates since the 1990s, or reduced rates of the proportion of people in extreme poverty.

From the mid-1990s to 2010, Vietnam, Indonesia and Cambodia have shown dramatic improvements in welfare conditions, especially as these countries have been experiencing considerable economic growth as well as implementing a number of successful pro-poor programs.

Indonesia, in particular, has implemented both a conditional cash transfer (CCT) and an unconditional cash transfer.

In contrast, the proportion of people in extreme poverty has been at a practical standstill in the Philippines.

Trends in the lack of changes in poverty headcounts from 2006-2012, whether using the country’s official poverty lines or the international poverty lines ($1.25 per person per day), have actually been quite similar. Thus achieving the first of the MDG targets on reducing extreme poverty and hunger by this year 2015 to half their levels in 1990 is close to impossible for the Philippines.

More recent poverty data from another survey instrument for the first semesters of 2013 and 2014 suggest reportedly a rise in poverty, but actually, a more careful reading of the press release of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) suggests that there was no change in the poverty rate. But because the 2014 survey did not include respondents in the province of Leyte (which was hit hardest by supertyphoon Yolanda), the national poverty rate is likely to be even higher than was estimated by the PSA.

Thus, the Philippines has yet to ensure that its recent economic growth benefits everyone. The wealthiest Filipinos whose wealth continues to rise will need to make more investments in the country that will ultimately assure sustained growth and progress.

Figure 2: Trends in Headcount Poverty Rates across selected ASEAN countries: 1980-2011.

Unfinished agenda

In the Philippines, there is evidence that some poor actually manage to exit from poverty, but for every poor who does exit poverty, there is about one non-poor who falls into poverty (likely from shocks of impacts of natural calamities, rising prices of food, loss of jobs, etc.), so the challenge is to set up social protection not only for the poor, but also for the nearly poor who can easily fall into poverty.

Although a fast-growing country like the Philippines will very likely not achieve its MDG targets on poverty reduction, and also on malnutrition, maternal mortality, reducing HIV/AIDS, but it will achieve some MDG targets on primary education for all, gender equality, sanitation and infant mortality.

Improvements in school participation appear to have been result of the government’s investments in addressing input deficits (classrooms, teachers, tables, chairs) with increases in budgets for the Department of Education (DepED), as well as in Pantawid Pamilya (our CCT) appear to be paying off with far fewer children of school going age who are out of school. With improved education attainments of children from poor families, it is expected that when these children join the labor market, incomes will likely be higher than what they would have had with less education.

In this end year for the MDGs, while much has been achieved, there is an unfinished development agenda even for the MDG targets that have been met.

Thus discussion on the SDGs has taken shape, with the UN Open Working Group on SDGs proposing double the number of Goals tin the MDGs (17 goals). Within the 17 proposed goals (see Table 2), there would be even much more targets (169) than the MDG targets, and likely there will be at least 300 statistical indicators to monitor for the SDGs.

Table 2. Proposed Sustainable Development Goals

| 1) End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| 2) End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture |

| 3) Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages |

| 4) Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| 5) Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

| 6) Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all |

| 7) Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all |

| 8) Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all |

| 9) Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation, and foster innovation |

| 10) Reduce inequality within and among countries |

| 11) Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable |

| 12) Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| 13) Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts |

| 14) Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development |

| 15) Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification and halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss |

| 16) Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels |

| 17) Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development |

Source: United Nations Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform

While undoubtedly, the MDGs was limited in scope, e.g., it did not cover targets on inequality and it was more concerned about poverty issues than a much broader framework, the current proposal on the SDGs is going overboard with too many goals that will likely undermine a clear focus for a development agenda, whether at the global, regional or country level.

The MDGs suffered from the lack of consensus on the targets and indicators, with a mere expert group from international organizations defining all the targets and goals. In contrast, the UN conducted many “global conversations,” which included 11 thematic and 83 national consultations, and even door-to-door surveys. It also conducted an online My World survey asking people to prioritize the areas they’d like to see addressed in the SDGs.

In 2013, the Open Working Group on SDG even invited official statisticians (that then included myself) to an informal meeting regarding measuring progress, which opened the doors for further discussions with official statisticians. Still, official statisticians have not managed to influence the Open Working Group into keeping things simple.

Setting priorities

The current proposal on the SDGs may have been spoiled by too many cooks, as it does not provide guidance to prioritize targets, but leaves it to regions and countries to to have a roadmap for prioritizing and attaining the SDGs according to context.

Past experience on MDG targeting, however, suggests that country capacities to identify targets are weak.

For instance, the Philippines defined a target to halve poverty rates from 1990, when this was very aspirational and did not take account of historical trends that would have suggested that this is going to be an extra challenge. In Myanmar, baseline indicators on poverty were from 2005, rather than 1990, and yet the government adopted a target to reduce poverty rates in 2015 to half the baselines, when the whole world used 1990 baselines, again making this more an aspirational than a realistic target.

It can also be observed that many of the proposed SDG targets are more of political statements than measureable achievements. Beyond the goals and targets for the SDGs, statistics will need to be identified, and more importantly, there will be a need to provide funds to sustain statistics for the SDGs, whether by governments or donors.

Sadly, even for the 60 MDG indicators, between half to two thirds of these statistics have been produced in ASEAN member states, and likely, for countries with less development and less statistical capacity, the availability of MDG statistics is not as good as in ASEAN (see Table 3). How then can we monitor what we do not measure, especially for countries in more need of development?

Table 3. Total MDG Indicators Produced in Selected ASEAN member nations

|

Country |

MDG Indicators |

||

|

Total Indicators |

Total produced by NSO |

Total produced by others |

|

|

Cambodia |

32 |

20 |

12 |

|

Indonesia |

48 |

28 |

20 |

|

Malaysia |

33 |

15 |

18 |

|

Myanmar |

49 |

3 |

46 |

|

Philippines |

42 |

18 |

24 |

|

Thailand |

54 |

6 |

48 |

|

Vietnam |

32 |

19 |

13 |

Sources: National Statistics Offices (NSOs) of Select ASEAN Countries

The UK Prime Minister David Cameron, who co-chaired a High Level Panel, that authored a report to discuss a post 2015 Development Agenda, has suggested trimming down the SDG targets to around ten.

Japan also is not happy about the current proposal. It will be important that the Philippines joins the UK and Japan in calling for a more focused development agenda. Otherwise, we may not able to prioritize actions to ensure that “no one is left behind.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.