SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] ‘Concrete cancer’: A warning about reclamations in Manila Bay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/06/tl-manila-bay-reclamation-sq.jpg)

Plans to reclaim many areas of Manila Bay’s nearshore continue to progress rapidly. But events here and elsewhere in the world continue to inform us just how dangerous doing so would be.

Nature’s most recent warning was the collapse last Thursday of part of the 12-story Champlain Towers South condominium complex near Miami, Florida. In the dead of night, 55 condos each worth $600,000 collapsed. As of this writing on Sunday night, nine corpses have been recovered, 152 are still missing, and hopes for their recovery are fading away.

We already know of three geological reasons why land reclamation of Manila Bay is a very bad idea that poses lethal risks to many people.

First, even without reclamation, the coastal lands around the Bay continue to subside rapidly because groundwater is being pumped out faster than nature can replenish it. This is worsening floods and high-tide invasions.

Philippine authorities now generally accept that global warming is raising sea levels by about three millimeters per year, and worry about how this rise must be aggravating Metro Manila flooding from both rains and high tides. But that is only about 1¼ inch every 10 years! Coastal Metro Manila is subsiding about 30 times faster, mainly because groundwater is being pumped out too quickly. If reclamation increases the number of people who rely on groundwater, the land will subside even faster. And the added weight of new high-rise buildings would also speed up the sinking of the land under them.

The second geologic threat to reclaimed areas is the combination of surges and storm waves driven against our coasts by passing typhoons. Supertyphoon Yolanda taught us how powerful storm surges can be. As our climate changes, supertyphoons and their storm surges are getting stronger and more frequent. The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) reports that the coastal areas targeted for reclamation have experienced typhoon surges up to four meters high. Depending on how long the typhoon winds last, and the timing and heights of the normal tides, a storm surge and the flooding it causes can last from hours to days. The havoc that storm surges wreak is magnified by huge waves that ride atop the surge, battering the coast.

The third, and by far the greatest hazard that threatens coastal areas, whether underlain by natural deposits like those of the Pasig river delta or artificial reclamations, is seismically-induced liquefaction. This is true for California’s Bay area as well as Manila Bay.

All bayfill materials, natural or man-made, are masses made up of pieces of rock ranging in size from tiny particles of clay to large boulders. Spaces between the solid pieces are occupied by water. Under normal conditions, the solid particles are in contact, so that the lower ones bear the weight of other grains above them as well as any buildings on top of them.

But during the minute or so that an earthquake lasts, the shaking breaks the contact between grains. Together, the shaking solids and water behave as a “slurry,” or liquid without strength, and buildings sink into it, or topple if their weights are unevenly distributed.

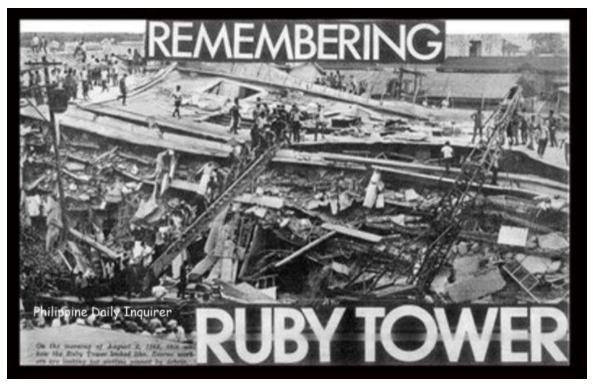

Reclaimed areas in Manila Bay would not require an earthquake to occur nearby to suffer serious damage. In 1968, Manila was hard hit by a magnitude 7.3 earthquake in Casiguran, Quezon, 225 kilometers away. Many structures that were built on river deposits near the mouth of the Pasig River were destroyed. The six-story Ruby Tower condominium building in Binondo collapsed. All six stories “pancaked” onto each other, killing 260 people trapped between them.

What does Thursday’s tragedy in Florida tell us? Florida undergoes hurricanes – the equivalents of our typhoons – and the storm surges they generate. But a hurricane was not a factor in the collapse.

Unlike the Philippines, Florida does not undergo frequent earthquakes, and one did not happen Thursday.

And yet, pictures of the “pancaked” floors of the collapsed Champlain Towers South are eerily reminiscent of the collapsed Ruby Tower.

The building was built on reclaimed coastal wetland. Clearly, the ground that it was built on was not of even strength, because only part of the structure gave way.

Investigations have yet to determine how much blame, if any, can be assigned to the reclaimed land under the building. But the failure of the structure can definitely be blamed in large part to “concrete cancer.”

All concrete is porous to some extent, and over the 40-year lifespan of the Tower, the nearshore salty air slowly soaked into the concrete. The steel reinforcing bars hiding in the concrete slowly rusted away until the structure became fatally weak.

Manila Bay shares the same oceanside environment and salty air.

Furthermore, exceptionally porous Pinatubo lahar sand, which makes concrete even more porous and cancer-prone, is being used for much of Metro Manila’s construction.

Philippine insurance community, take particular notice. – Rappler.com

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Voices features opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Fossil fuel debts are illegitimate and must be canceled](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/IMHO-fossil-fuel-debt-cancelled-April-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[WATCH] John Kerry: You can’t solve climate crisis without addressing ocean’s challenges](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/cop28-united-states-john-kerry-december-2-2023-reuters-001.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] Lessons in resilience from Japan’s New Year’s Day earthquake](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/TL-japan-earthquake-warning-system-jan-3-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.