SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Debunking the deadly lies of Duterte’s economic managers](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/04/tl-debunking-lies-sq.jpg)

Many of the present woes of the Philippines can arguably be traced to the sheer stubbornness and hubris of President Rodrigo Duterte’s economic managers.

First, they were the ones who kept on insisting that we ought to relax quarantine restrictions even as the country’s pandemic response was barely improving (indeed deteriorating in many respects), and even as new COVID-19 variants were being discovered. (READ: New surge? Duterte reopened economy too quickly)

Second, they were the ones who kept repeating that the government could not afford to spend massive sums of money on fiscal stimulus and relief, and that such expense was “unsustainable.”

These are big fat lies that need to be debunked once and for all.

Major lie #1: There’s a trade-off between public health and the economy. (There’s none.)

The biggest, most pernicious lie of all is the claim that there’s a trade-off between public health and the economy. You won’t hear them say that exactly, but that’s how they keep framing the crisis anyway.

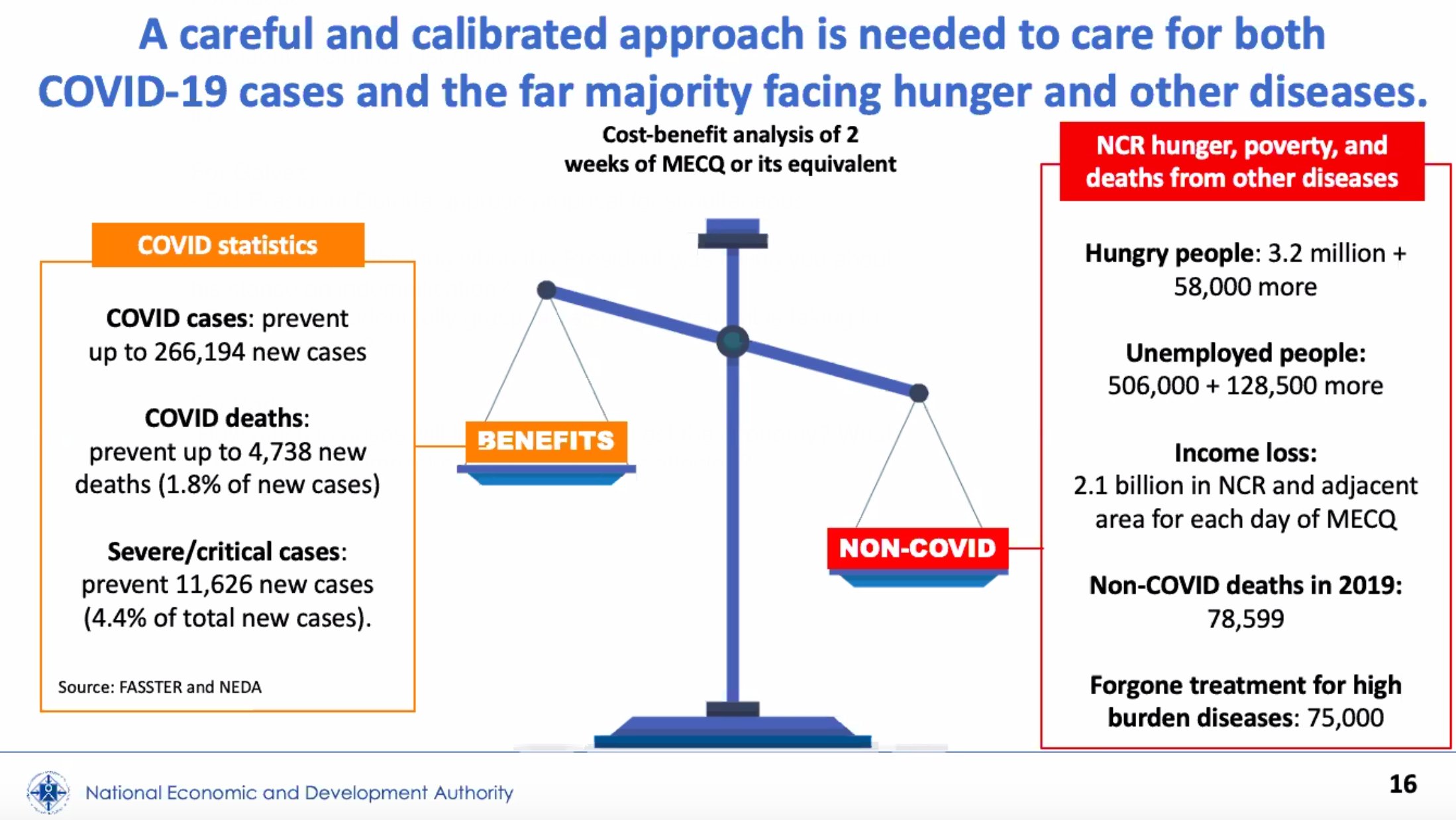

This point is summarized in Figure 1, a slide shown by NEDA chief and Socioeconomic Planning Acting Secretary Karl Chua in press briefings before Duterte reinstated the strictest lockdown mode in the “NCR Plus” bubble.

There’s a weighing scale that’s supposed to show a “cost-benefit analysis” of imposing stricter quarantine measures. On the one hand, you have the benefits of lockdown, including the prevention of new cases and deaths of COVID-19. On the other hand, there are costs such as hunger, unemployment, income loss, as well as deaths arising from “non-COVID” diseases.

Figure 1. False trade-off.

No self-respecting economist would ever frame the crisis this way.

Despite the self-evident trade-off in Figure 1, Secretary Chua says there’s no trade-off at all — that is, when you take into account the “total health” of Filipinos. In his view, the thousands of people dying from non-COVID illnesses are an argument for the economy’s quick reopening.

But he misses the point entirely: so long as COVID-19 patients overwhelm our hospitals (as they currently do), it will be extremely hard to take care of non-COVID patients, too — let alone reopen the economy safely. Everything hinges on containing COVID-19 first.

It’s not that difficult to grasp the consensus that has emerged among economists early last year: there’s no trade-off between public health and the economy. The recession ultimately stems from a health crisis, and without addressing that first and foremost — by, say, mass testing, contact tracing, and hospital capacity improvements — no reasonable economic recovery can be expected.

In fact, some economists recently came out with an article arguing that aiming for zero COVID-19 cases may be the “cheapest path towards economic recovery.” Put another way: “The trade-off between health and wealth has been refuted by countries that have opted for an elimination strategy.”

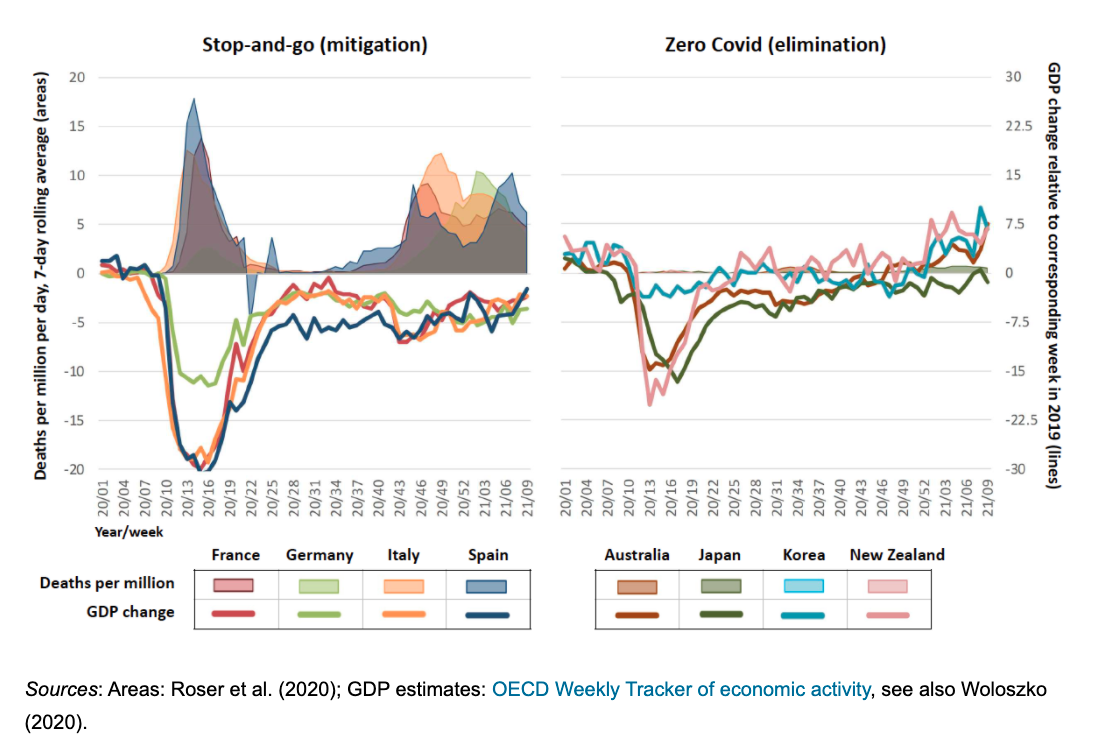

Figure 2 illustrates their main point: for countries like New Zealand, Australia, and South Korea that sought to eliminate COVID-19 (and have successfully done so), economic growth is now back (or will soon be back) to pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, European countries that adopted a “stop-and-go” approach (closing and reopening their economies depending on the rise and fall of COVID-19 cases) are still far below pre-pandemic growth levels.

Figure 2. Daily deaths per million (areas) and weekly GDP estimates (lines). Source: Aghion et al. [2021].

Apart from being disruptive in the short run, the stop-and-go approach “is detrimental for long-term economic growth because it prevents firms from planning ahead for the long term. Instead of investing in innovation, they accumulate cash to face the next lockdown. Instead of investing in skills, they hire on a short-time basis.”

The full piece is worth a read, alongside dozens of new studies similarly debunking the health-economy trade-off. Hopefully, Duterte’s economic managers take the time to read them, too.

Major lie #2: Government can’t afford ayuda. (It can.)

Duterte’s economic managers have also consistently rebuffed calls for massive aid (ayuda) by saying it’s “not fundable,” that we need to exercise “fiscal prudence,” or that we ought to “guard” our credit ratings “very well.” To avoid giving aid, let’s just reopen the economy, they say.

But again this is misleading for a number of reasons.

First, money isn’t a real problem. Sure, tax revenues have dwindled of late. But government has had no trouble borrowing recently, whether from domestic investors, multilateral agencies like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, or even our own Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas.

Second, Duterte’s economic managers worry too much about the deficit and the debt. As I wrote before, a paradigm shift has recently swept economists across the globe: they’ve changed their tune when it comes to public debt, and are now open to huger amounts of it so long as governments can address the global pandemic and give aid to their citizens.

Somehow, though, this lesson is lost among Duterte’s economic managers. Preliminary data show our government is grossly underspending relative to the extent of economic losses we have sustained (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

If you ask Secretary Dominguez, “Prudence dictates that we keep our powder dry. We should be able to finance fighting the second wave should this happen.”

But this is not at all the right analogy to use. In this war the enemy likes to spread exponentially, and the longer it takes for them to act aggressively against it, the longer and harder the battle will be. Besides the pandemic and the recession, what on earth are they “prudently” saving money for?

Much more worrisome than the ballooning deficit and debt is the P4.5 trillion 2021 budget which the economic managers submitted to Congress last year. (READ: Debt is rising fast, but worry more about Duterte’s spending)

Besides failing to allocate enough money to relief and the vaccines, the economic managers also poured money into Build, Build, Build and pushed for a huge corporate tax cut that will almost certainly drain the public coffers further. All this despite the government’s supposed lack of money. Where’s the fiscal prudence there?

Third and last, credit ratings ought to be the least of the economic managers’ concerns. With global interest rates at a historic low, we’re at little risk of defaulting on our loans. Besides, a protracted pandemic recession brought about by underspending is far more worrisome than a potential credit rating downgrade.

The economic managers’ obsession with credit ratings has already backfired. Moody’s, a credit rating agency, said that the Philippine economy is in a “worrisome state” and the recent surge of cases is a “credit negative.”

Politics vs. economics

It’s bad enough that Duterte’s economic managers have long clung to dangerous misconceptions. Worse, other influential policymakers — even those well outside the Cabinet — unthinkingly follow their lead as chicks follow their mother hen.

For instance, Metro Manila’s mayors agreed with Secretary Chua’s proposal to impose the least restrictive quarantine mode in Metro Manila in early March. They were later thwarted by Duterte, but mayors and governors in other regions have loosened their quarantine restrictions while citing the need to rescue their respective economies.

Meanwhile, key lawmakers have echoed the idea that government can’t afford a sizable fiscal response, and Congress ultimately failed to correct the misguided priorities in the original budget proposal.

A new bill called Bayanihan 3, a proper and sound relief package advocated by a legitimate economist, is taking too long to pass. By lawmakers’ utter lack of urgency, you’d think the economic crisis was over.

In place of Bayanihan 3, the economic managers think we first ought to exhaust unspent funds in the previous budget as well as Bayanihan 2, both of which have been extended. But that’s like trying to fight a raging fire with buckets of water rather than with the fire truck just sitting on the corner.

More and more people, especially public health experts, are getting frustrated over Duterte’s economic managers, who seem to have an outsize influence in policymaking nowadays despite this being a health crisis above anything else. As if that weren’t enough, on March 31 one “economist” lawmaker proposed that Secretary Dominguez be delegated as the government’s chief pandemic crisis manager. I thought it was an early April Fool’s joke.

Seriously, the economic managers need to disabuse themselves of their mistaken (frankly, deadly) notions about how the economy works. Until they do (or until they are replaced), expect endless cycles of economic opening and closing. More people will needlessly die, and the economy will take forever to recover. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Time Trowel] Evolution and the sneakiness of COVID](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/tl-evolution-covid.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=455px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Newsstand] The Marcoses’ three-body problem](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcoses-3-body-problem.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=451px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Edgewise] Preface to ‘A Fortunate Country,’ a social idealist novel](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/a-fortunate-country-february-8-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[New School] When barangays lose their purpose](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-barangay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.