SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Dismal PISA rankings: A wake-up call for Filipinos](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/42F5C70399944234B3AB20D6516AC1CC/img/9BE6AF45291C433A81CDDC21FE2B9A07/Dismal-PISA-rankings--A-wake-up-call-for-Filipinos.jpg)

We all have a sense there’s something wrong with the Philippine education system. But we didn’t know it’s this bad.

Recently the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released the results of the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

Conducted every 3 years since 2000, PISA is one of the most famous student assessments worldwide, and certainly among the most influential in terms of research and policy.

Primarily PISA “measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges.”

Last year Filipino students participated in PISA for the first time ever. It’s the first chance for our students to be compared with their global peers using this renowned benchmark.

Lo and behold, the results were rather dismal (Figure 1). Among 79 participating countries or economies the Philippines ranked dead last in reading, and we ranked second last in both mathematics and science (beating only the Dominican Republic).

Notwithstanding PISA’s many imperfections, these are appalling outcomes for the Philippines.

What gives? How come we ranked poorly? What does this say about the state of Philippine education?

Figure 1

Overview of results

The OECD provides a discussion of the PISA 2018 results focused on the Philippines.

Some of their findings weren’t all that surprising. For instance, when it comes to reading (this PISA round’s subject in focus), they found that richer students tended to outperform poorer students, while females tended to outperform males.

But other findings were quite striking.

For instance, almost two-thirds of Filipino students “reported being bullied at least a few times a month.” More than a fourth said they felt lonely at school. And more than a third said “their teacher has to wait a long time for students to quiet down.” All these proportions were higher than the OECD averages.

Moreover, 72% of our students (versus 56% in OECD) said that when they fail “they worry about what others think of them.” And only 31% of our students (versus 63% in OECD) supposedly hold a “growth mindset” – meaning students think they can improve their intelligence through hard work.

In all this, of course, you might (rightfully) say it’s unfair to compare the Philippines with OECD countries, which comprise some of the most advanced countries and economies of the world.

But note that PISA 2018 comprises many non-OECD countries, too, including 5 of our Southeast Asian neighbors (only CLMV or Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam were excluded). Using the same yardstick, we still fared worse than our neighbors.

Note, too, that Asian countries like China and Singapore tend to predominate in the PISA rankings, much to the chagrin of actual OECD members.

Education problems galore

Why these dismal rankings for the Philippines?

First, you might suspect we’re not spending nearly enough on education vis-à-vis other countries.

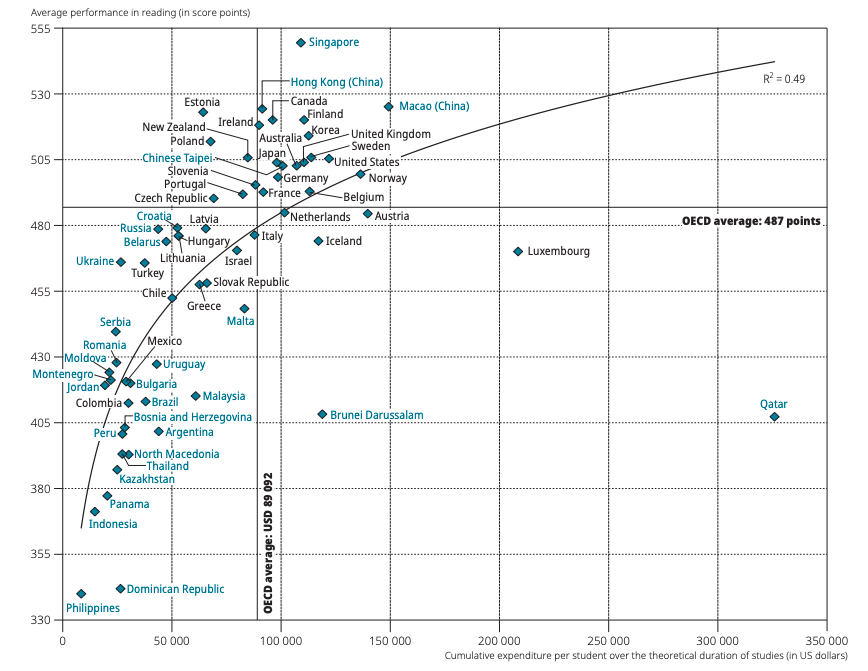

Figure 2, coming from the full PISA report, seems to corroborate this. Notice the positive correlation between reading scores and education spending. The Philippines unsurprisingly comes out at the bottom end of this plot. On the bright side, this implies every extra peso spent on education could still yield high returns.

Figure 2. Reading performance vs spending on education. Source: PISA 2018, OECD

But for the proposed 2020 budget, I noted before that the Duterte government is pushing for disturbing budget cuts in both basic and higher education. (READ: Duterte’s perverse priorities in the proposed 2020 budget)

At the same time, education already takes the lion’s share of the government’s budget each year, as provided for by the 1987 Constitution. Clearly, ensuring quality goes well beyond money matters.

This brings us to a discussion of the “Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013,” otherwise known as the K-12 law.

The previous administration touted K-12 as the biggest educational reform in decades. One of its goals was to “Give every student an opportunity to receive quality education that is globally competitive based on a pedagogically sound curriculum that is at par with international standards” (emphasis mine).

Clearly, based on PISA 2018, our education system now is still neither “globally competitive” nor “at par with international standards.” We still have such a long way to go.

By adding two more years in senior high school or SHS, K-12 did align our country with the customary length of basic education systems abroad.

But in a previous piece I explained that teachers and school administrators were largely ill-prepared and ill-equipped during the transition to SHS. Right from the get-go, the Department of Education (DepEd) also failed to track the movements of students from junior to senior high and beyond. (READ: Why senior high school needs urgent fixing)

As a result of these and other hiccups, the performance of K-12 graduates has been largely mixed, at least anecdotally.

University professors have given feedback that college freshmen today think and act more maturely than their predecessors (students now graduate from high school at around age 18). But professors also complain they find themselves re-teaching basic ideas and skills that freshmen were supposed to have mastered in high school – but for some reason haven’t.

This is not to say K-12 has been a complete failure. We have yet to see robust empirical studies on its impacts. But K-12 certainly has much room for improvement.

There are also deeper, more structural issues that beset our education sector.

For instance, as noted in a policy note of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, in our basic education system there is currently a phenomenon of “mass promotions.”

That is, in a bid to minimize dropout rates, teachers and school administrators are incentivized to allow non-readers and other poorly performing students to move up the educational ladder.

Apart from this, we have the long-standing issue of educational inequality where, essentially, students from richer and urban backgrounds have access to better-quality schooling than their poorer and rural counterparts.

Wake-up call

There’s a risk we may be beating ourselves too hard over the PISA 2018 results.

For one, PISA has its fair share of criticisms. Tons of academic articles have debated whether PISA reliably measures literacy or intelligence in general. PISA rankings are also based on country averages, thereby hiding the rich distribution of students’ performance in each country.

Some researchers also point out that each PISA study tends to spawn an ugly “horse-race” among countries, as well as sweeping generalizations about countries’ educational systems based solely on their PISA rankings.

Some Philippine educators focus on the silver lining. The mere fact that DepEd allowed our students to join PISA for the first time is, in itself, commendable.

At least we now have baseline data that we can use to compare our country’s PISA performance with other countries and track our progress moving forward. It’s much better than groping in the dark.

When all is said and done, may the PISA results open our eyes to the education crisis staring us in the face. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.