SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Marcos na rin? Authoritarian dispersion in PH party politics](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/11/TL-Authoritarian-political-parties-November-25-2021.jpg)

Read first part: Vestiges of authoritarianism and return of Marcos dynasty

Read the final part: [ANALYSIS] Authoritarian contamination after EDSA

Personalities formerly identified with fallen dictatorships do not survive only in authoritarian successor parties, they also disperse across multiple parties and electoral vehicles.

According to Loxton and Power, authoritarian diaspora refers to “a pattern of dispersion among former authoritarian officials (the ‘authoritarian cohort’) in the lead-up to, or the aftermath of, a transition to competitive elections.” These personalities can exit from former authoritarian ruling parties by 1) forming new parties; 2) colonizing existing parties; and 3) running as independents.

Similar to authoritarian successor parties, the phenomenon of authoritarian diaspora can be considered a double-edged sword hanging over democratizing polities. While dispersion can provide an avenue to reintegrate authoritarian personalities into democratic politics, on balance, its effects may be more harmful than authoritarian successor parties due to:

- overrepresentation of the authoritarian cohort under democracy;

- persistence of authoritarian-era practices and institutions; and

- dilution of the regime cleavage between defenders and opponents of the former dictatorship

In the post-Marcos period, patronage politics and party-switching continued to weaken democratic institutions, leading to their further erosion. The authoritarian virus, dormant for decades, gradually infected most of the country’s party politics in various ways.

First, the elite-led and negotiated democratic transition since 1986 provided the opportunity for the rehabilitation of key enablers of Marcos’ authoritarian regime. It allowed former Marcos associates and Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) members to switch easily and even take up leadership positions in the post-authoritarian political parties.

Second, patronage-based party switching fueled the rise of KBL-like monolithic parties in succeeding presidential administrations – from the Laban ng Demokratikong Pilipino (LDP) during the term of Corazon Aquino, followed by the Lakas-NUCD-UMDP founded by Fidel Ramos, the Laban ng Makabayang Masang Pilipino (LAMMP) of Joseph Estrada, the Kabalikat ng Malayang Pilipino (Kampi) of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the Liberal Party (LP) under Benigno Aquino III, and the PDP-Laban under Rodrigo Duterte. Third, the Marcos dynasty gradually rebuilt their political base by recapturing their provincial bailiwicks in Ilocos Norte and Leyte and re-entering national politics by winning seats in the Senate.

Since the once monolithic KBL immediately crumbled after the dictator fled to Hawaii, a large number of its leaders and members gradually but resolutely exited to affiliate with the emergent post-authoritarian parties.

Authoritarian dispersion

In a recent article, Buehler and Nataatmadja argued that “the two variables shaping defection calculi are the prevailing levels of party institutionalization (of both the authoritarian successor parties and alternative parties) and the type of reversionary clientelistic network available to elites in post-transition politics.” Since the KBL was poorly institutionalized and clientelistic relations offered a more stable basis for voters’ mobilization, it was relatively easy to disperse into other parties. Thus, the majority of the authoritarian cohort from the KBL defected to other post-authoritarian parties.

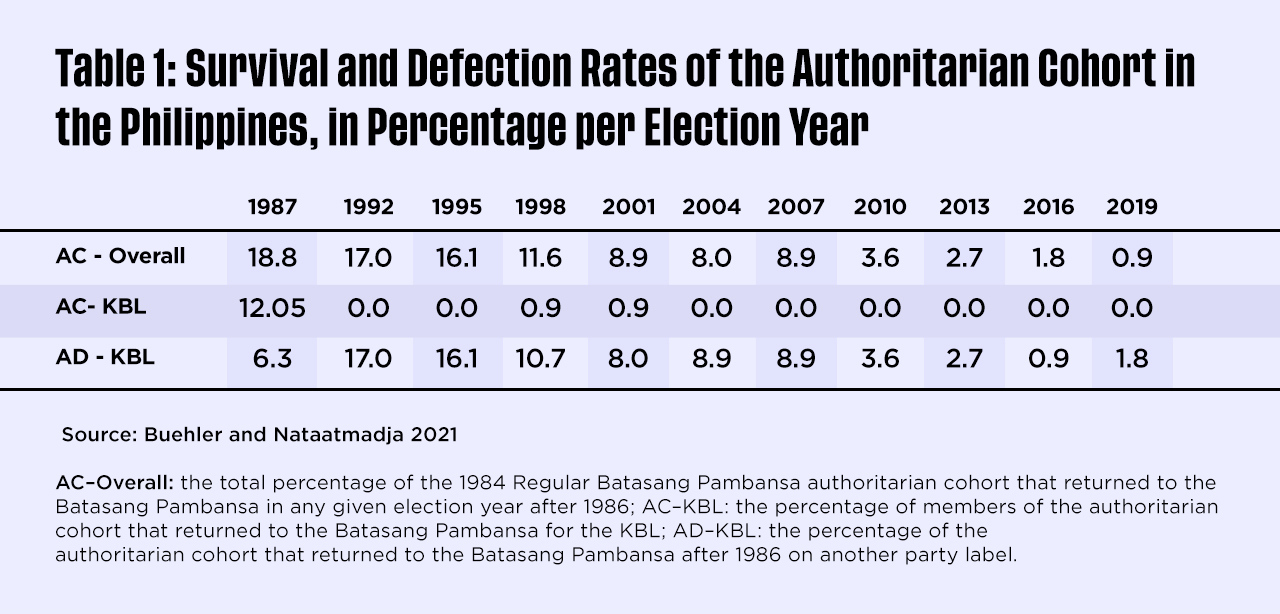

In the same study, the survival and defection rates of the authoritarian cohort were tracked and counted: the overall KBL members who sat in the regular Batasang Pambansa in 1985 and who won a seat in the national legislature on another party label after 1986 (see Table 1). The data reveal a significant number of authoritarian dispersions even way beyond the immediate period of democratic transition. This can be contrasted with the Indonesian case in which authoritarian diaspora was minimal and vanished quite quickly from national legislative politics.

The large rate of authoritarian diaspora in the Philippines can be attributed to what Aspinall and Hicken calls “relational clientelism” rooted in more durable social relations that often last for decades. Thus, members of the authoritarian cohort were far better prepared to survive in the newly democratic environment. Numerous members of the KBL authoritarian cohort were derived from local dynasties and hence possessed autonomous power bases from the state. While the Marcos family made large quantities of money accessible to KBL members prior to the 1984 elections, many members of the authoritarian cohort competed in elections throughout the Marcos regime using their own personal networks.

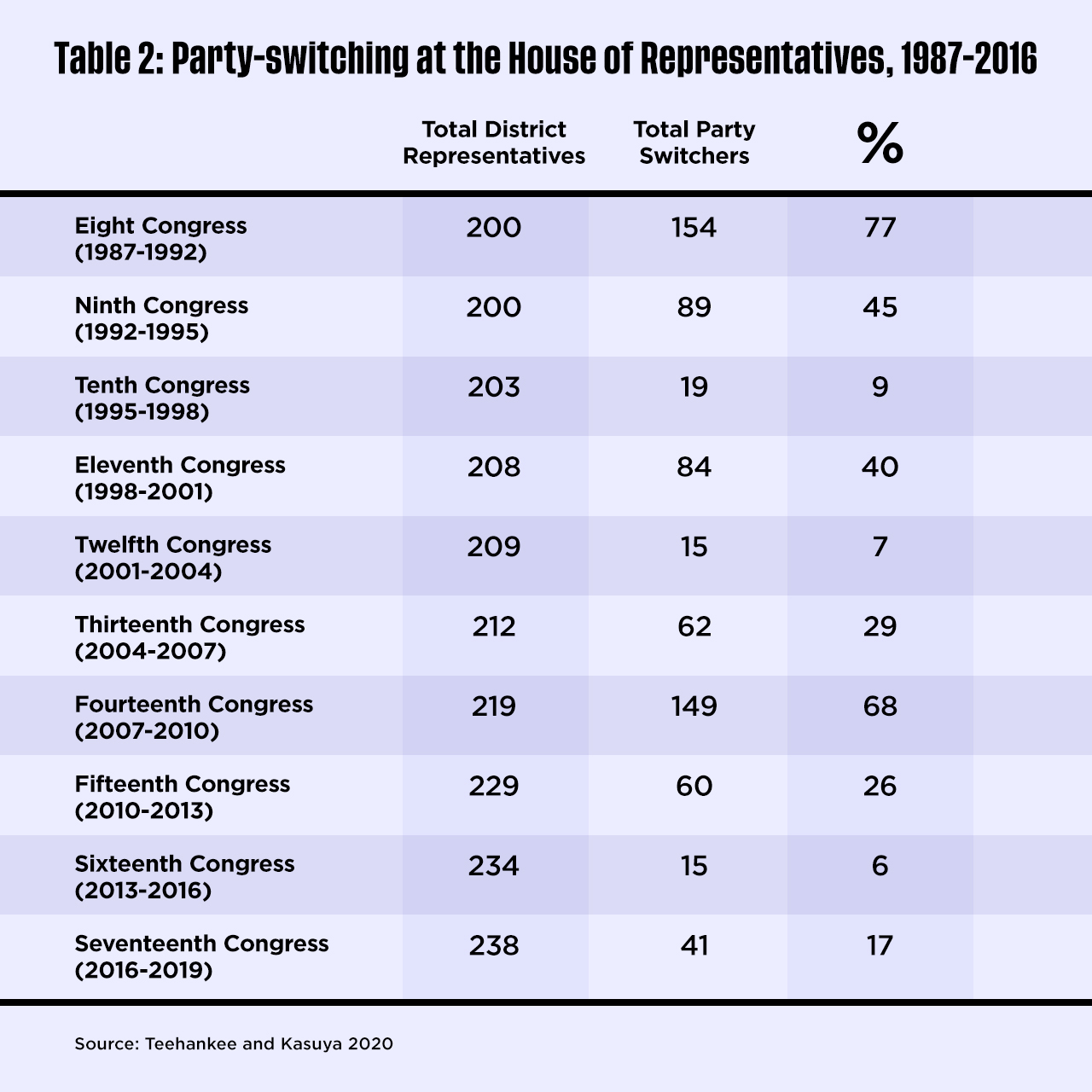

Following the dictator’s downfall in 1986, these local oligarchs simply continued to rely on their long-established machineries. Another factor not mentioned in the study is the high rate of party-switching in the Philippines. According to Teehankee and Kasuya, an average of 32% of district representatives was elected from the 8th to 17th Congress between 1987 and 2019 (see Table 2). The lethal combination of dynastic politics and constant party-switching has contributed to a variant this author terms as “authoritarian contamination.”

Authoritarian contamination

In the 2019 midterm elections, the ruling PDP-Laban under President Rodrigo Duterte endorsed the senatorial candidacy of Imee Marcos. She was a candidate of the NP, which was in coalition with the PDP-Laban. Earlier, Imee’s cousin and nephew of former first lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos, Leyte Representative Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, assumed the presidency of the Lakas-CMD party. Romualdez has been a high-profile party member since the administration of former president Arroyo. The PDP-Laban was the party that fielded populist Rodrigo Duterte for the presidency in 2016. Lakas-CMD not only backed Duterte but also the failed vice-presidential candidacy of Bongbong Marcos. Both PDP-Laban and Lakas-CMD have roots in the anti-Marcos struggle and the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution.

Authoritarian contamination is a more potent variant of authoritarian diaspora in which personalities closely identified with fallen authoritarian infecting or contaminating “democratic parties” (i.e., parties that struggled against authoritarianism or were founded in its aftermath to consolidate democratic gains). The following will discuss the democratic parties that emerged during and after the struggle against the dictatorship and how these parties were contaminated by vestiges of authoritarianism.

PDP-Laban: From democracy to populism

Despite ascending to the presidency under the banner of PDP-Laban, Cory Aquino refused to formalize her affiliation with the party. Instead, her brother Jose “Peping” Cojuangco Jr. assumed the leadership of the party. From its inception, tensions have been felt between the reform-minded activists within the party and its traditionally oriented political partners. This was exacerbated by Cojuangco’s slide towards political pragmatism. Unlike PDP-Laban founder Aquilino “Nene” Pimentel Jr, Cojuangco did not adhere to the party’s ideology. He started recruiting turncoats from other parties, including notorious elements from the KBL.

Later, Cojuangco orchestrated the merger of PDP-Laban and another pro-Aquino party – the Lakas ng Bansa – largely composed of party-switchers from the United Nationalist Democratic Organization (UNIDO) and the KBL. This would result in the formation of the LDP.

The highly decimated PDP-Laban led by the late Senator Pimentel Jr. and then-Makati mayor Jejomar barely survived as a minor party entering in and out of alliances and coalitions. In 1992 it entered a coalition with the Liberal Party to support the presidential candidacy of Senator Jovito Salonga. In 2004 it reunited with the LDP in an alliance with the PMP known as Koalisyon ng Nagkakaisang Pilipino (KNP) to support the presidential candidacy of populist actor Fernando Poe Jr. Practically half of the KNP senatorial slate included personalities formerly identified with the Marcos authoritarian regime that included: Juan Ponce Enrile, Salvador Escudero, Jinggoy Estrada, Alfredo Lim, and Francisco Tatad. Ironically, the slate also included the staunchly anti-Marcos Nene Pimentel.

Binay was elected vice president in 2010 under the banner of the dormant PDP-Laban. In preparation for the 2013 elections, Binay formed an electoral alliance with the PMP to form the United Nationalist Alliance (UNA). Binay resigned from the PDP-Laban in 2014, after serving as a party stalwart since the party’s foundation in 1983. Following Binay’s decision, the PDP-Laban, led by Senator Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III, the son of the PDP-Laban founder, opted to withdraw from the UNA alliance as well. Binay relaunched UNA as a political party in 2016 to campaign for the presidency.

Following Binay’s departure from the PDP-Laban in 2014, the PDP-Laban became the country’s ruling political party after the 2016 presidential elections. Rodrigo Duterte, the Davao City mayor and standard-bearer of the PDP-Laban, won the five-way contest with 39.01% of the overall popular vote. Less than three weeks after the elections, the PDP-Laban’s multi-party coalition Coalition for Change effectively attracted up to 260 allies, or 90% of the around 290 members in Congress.

By this time, the PDP-Laban has been fully infected by the authoritarian populism of Rodrigo Duterte, who has openly admitted his admiration for the dictator Marcos. – Rappler.com

This three-part series is an abridged version of the chapter “The Legacy of the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan: Authoritarian Contamination in Philippine Party Politics” written for an edited volume marking the 50th anniversary of the declaration of martial law to be published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press in 2022. The full version of the chapter will also be released as a working paper by the La Salle Institute of Governance. (Read the first part here.)

Julio C. Teehankee is professor of political science and international studies at De La Salle University. He appears regularly as a political analyst for local and international media outlets and his YouTube channel – “Talk Politics with Julio Teehankee.”

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Marcos: A flat response, a missed opportunity](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcos-flat-response-april-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.